Jackson Atsango, director of Springs of Grace primary school in Kenya, has initiatives in place at his school to protect his young students from trafficking. (Kaitlyn Schallhorn/TheBlaze)

Editor's note: TheBlaze reporter Kaitlyn Schallhorn recently spent 16 days in Kenya reporting on issues affecting the lives of people in this African nation. Here is the first part of her series.

BUTERE, Kenya — The heat is already oppressive outside, but within the small tin-roof classroom, it’s almost unbearable.

Dust and dirt swirl constantly, both inside and outside. Devoid of desks, textbooks, maps, or artwork, the haphazard chalkboard at the front of the room serves as the only focal point of learning as two grades cram into one room to learn.

But still, these learning conditions aren’t the most concerning for many educators in western Kenya, including science teacher Samuel Warwire. Pointing to a group of about 20 to 30 girls running and playing outside Eshibina Primary School, Warwire, 35, speculated that many of them would drop out of school by the age of 12.

Warwire’s prediction was repeated at multiple public and private schools toured by TheBlaze. And while some educators would remain mum on the exact reasoning behind such an increase in female student dropouts, most were forthcoming about the problem of child trafficking in the country.

Accurate statistics on the propensity of child trafficking in Kenya are fairly nonexistent, but it’s a glaring reality in many villages — seen particularly in schools, according to several dozen educators in multiple interviews with TheBlaze over the course of one month.

Even with a lack of concrete data on trafficking in Kenya — particularly western Kenya — educators also recognize another brazen problem in their communities: the lack of protection parents or guardians provide their daughters.

Gabriel Andako, who has taught for 14 years at a private school (through eighth grade) in western Kenya, told TheBlaze that oftentimes a young girl will realize the crippling poverty her family is in and think that leaving home to work at a young age will help. And that thought is often perpetuated by family members who will encourage her to go overseas to the Middle East or to Nairobi for work.

Families know that the work and money promised might not actually exist, but sometimes it’s a risk they are willing to take, said Andako, who is also a 15-year volunteer children’s officer with the local government.

Once away from the families and communities, the reality of the "job" will set in and girls will find themselves being used for sex or hard labor.

“These parents or grandparents or guardians, they feel that this girl can go and work and bring economic aid,” Andako said. “It’s one less mouth to feed. And some also feel that currency [in other countries] is higher so they’ll be getting much money.”

Andako added that house helps in Kenya make around 1,500 to 2,000 Kenya shillings (approximately $14.50 to $19.30) per month but are often promised 15,000 to 20,000 ($145 to $193) if they go with "agents" — the men who convince young girls to leave the country for work.

“They feel this money will help the home, but these girls are still a child,” he said.

Girls often lose contact with their families, forbidden to call home unless it’s to recruit other girls, Andako said. And too often, should they return home at all, it’s in a box.

Parents also remain tight-lipped about the whereabouts of their daughters should friends, relatives, teachers, or government employees inquire. Many times, parents simply say a daughter has gone to live with a relative in Nairobi in order to attend better schools.

With parents remaining mum — often out of fear of punishment for a truant child — the government can’t step in and aid these trafficked children, said Grace Bakesia, an employee with the Buture Sub-County Children’s Office, a part of the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Development.

“It’s a failing society,” Bakesia said when asked if parents aren’t doing enough to protect their children. “It’s not necessarily the parents’ fault. It’s a failing society.

“It’s a failing kinship system,” she said. “It is a matter of individualism.”

Another issue is that once someone alerts the government to a neglected girl, someone will need to step up and take care of the girl until the courts can figure out a permanent solution — and no one is ever willing to do that, Bakesia said.

And there’s also the matter of money. In an already poverty-stricken area, should a family come forward and admit to officials that a daughter has been taken somewhere and contact was never established, the family almost certainly will not have the funds needed to travel, find her, and bring her back.

What the government office can do, Bakesia said, is offer high school scholarships to girls, promote community groups to raise awareness in the area and host assemblies with children representatives from schools on issues that impact them, such as neglect, female genital mutilation, sexual abuse and incest. And anyone can report an issue to the office through a helpline.

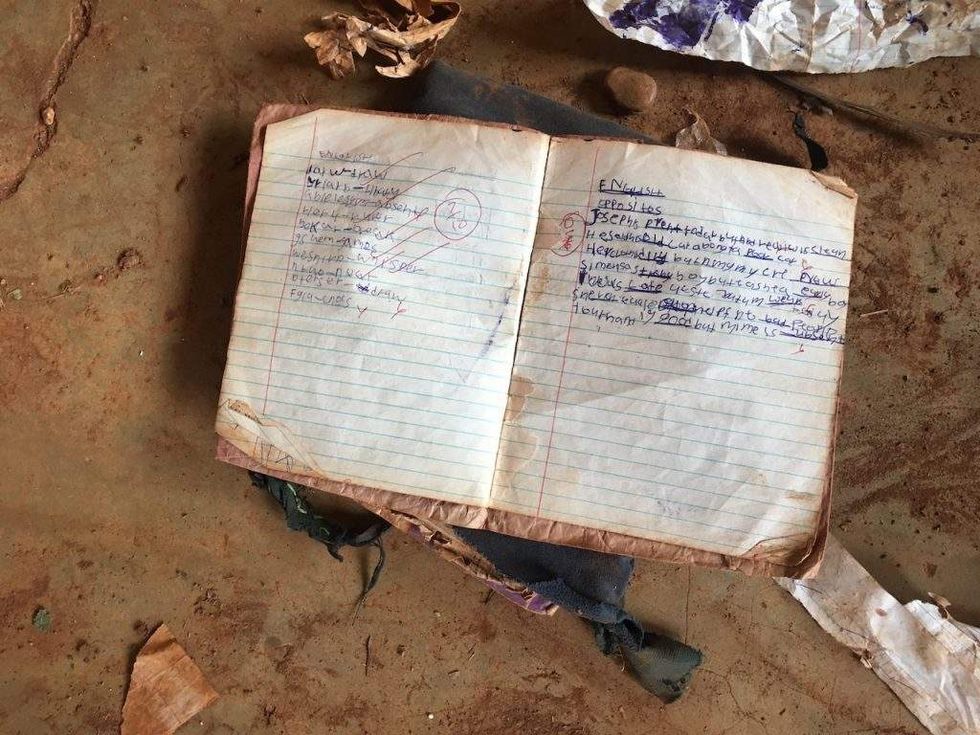

With parents and the local government unable or unwilling to help, educators such as Jackson Atsango at Springs of Grace school in Butere are stepping up to the plate.

Atsango began Springs of Grace in 2007 to serve an area that had a problem educating girls — most girls were dropping out around fourth or fifth grade to get married. Girls Not Brides, an organization aimed at ending child marriages, estimates that at least 23 percent of Kenyan girls will be married before the age of 18.

"[M]any girls in rural parts of Kenya are often perceived by their families as either an economic burden or valued as capital for their exchange value in terms of goods, money and livestock," according to Girls Not Brides. "To justify these economic transactions, a combination of cultural, traditional and religious arguments are often employed."

The organization estimates that 67 percent of women from 20 to 24 years old without an education were married as a child. However, only 6 percent of women who married while a child have at least a secondary education.

Atsango noticed this in his area — including with members of his own family — and told TheBlaze that oftentimes young girls will be approached during their long journey to school by men who can persuade them to marry young so as not to become a financial burden on their families.

“They look at the distance, and it’s very far [to walk to school]. Eventually as they walk, they meet some men on the way,” Atsango explained. “They get confused, and they get married.”

And child labor, too, is “very common,” he said, especially if the young girls are impregnated at a young age and are forced to provide for a child.

As Bakesia, the government employee, explained, these young marriages will fail as young girls "cannot keep up with the demands of marriage." Then, children will come back to their families, leave their newborn children at home and leave to find work — any work at all — to try to provide economically for the new children.

“We have this issue of Saudi Arabia now which is very common,” Atsango said. “They are looking for house helps or just workers. They don’t need any qualification. We have some agents that are taking [children] out of their homes. That’s become very common.”

According to teachers, some students are taken off the streets unwillingly.

“Just last week we had an issue with a guy who had a vehicle who was picking kids [up] on the way home from school,” Atsango said. “I was called, I was told to be cautious and don’t allow kids to go into the road. These people are picking kids [up] on their way home.”

But others, as Astango pointed out, leave willingly with "agents" in the hopes that the job promised will be better than no job at all.

“What happens, especially with our low-income families in the community, if somebody comes to pick your child, whether you’re paid or not, you just say hallelujah just to go [for that opportunity]. That’s what is happening with us,” Atsango said, adding that some families are “relieved” to be able to just “release” a child due to economic issues.

So in order to educate girls in the area, Atsango keeps his students in school all day — from around 6:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Students will also be given homework to be completed each night that needs to be signed by a parent or guardian.

“Also, our motto is about discipline and hard work,” Atsango explained. “We help them, we counsel them, talk to them, we encourage them and show the importance of why they should be in school.

“Now, bringing this school here has brought a challenge for some [girls],” he continued. “Now they start finishing school at grade eight, and they’re better off.”

Atsango said the school also “sensitizes” children to the issue as other educators ban together to warn each other of potential problems. The government, he said, depends on teachers to help alleviate the problem.

The initiative by teachers is widespread. In a small school outside of Malindi — a town along the coast of the Indian Ocean — a teacher who asked to be identified only as Jacob told TheBlaze that he will begin his journey to school hours before needed. On the way, he’ll meet up with another female teacher and the pair will walk paths they know some young girls take in the mornings. They hope to intercept the girls to ensure they arrive to school safely.

“We also encourage their male peers to help and offer to walk them home,” Jacob said.

Jacob, who declined to give his last name and asked that his school be kept anonymous, said he sees the female population in the school drop by two-thirds once girls reach the age of 11 or 12. He said he’s seen traffickers in the area and was afraid of the repercussions on the school or students.

As Kenya’s Daily Nation reported in 2015, the U.S. has noticed the trafficking problems in the country and included in a report that “hundreds of Kenyans are … exported for domestic jobs in Oman, Qatar, Lebanon, Serbia and Saudi Arabia, among other countries.”

According to the Daily Nation:

The report also reveals that hundreds of gay and bisexual Kenyans are lured from Kenyan universities with promises of overseas jobs but are forced into prostitution in Qatar and the United Arabs Emirates.It further discloses that Kenyan women are subjected to forced prostitution in Thailand by Ugandan and Nigerian traffickers.

The report said that though Kenya had not complied with minimum standards for eliminating trafficking, some positive efforts have been made.

A 2016 report by the U.S. State Department states that “children are subjected to forced labor in domestic service, agriculture, fishing, cattle herding, street vending and begging.”

It states:

Girls and boys are also exploited in prostitution throughout Kenya, including in sex tourism on the coast; at times, their exploitation is facilitated by women in prostitution, “beach boys,” or family members. Children are also exploited in sex trafficking by people working in khat (a mild narcotic) cultivation areas, near Nyanza’s gold mines, along the coast by truck drivers transporting stones from quarries, and by fishermen on Lake Victoria. Kenyans voluntarily migrate to other East African nations, South Sudan, Angola, Europe, the United States, and the Middle East — particularly Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Oman — in search of employment, where at times they are exploited in domestic servitude, massage parlors and brothels, or forced manual labor.

Jakob Christensen, program manager for the nongovernmental organization Awareness Against Human Trafficking, or HAART, which works to end modern slavery in Kenya, stressed that there is a “general lack of research and statistics on human trafficking in Kenya.”

“We think it is a very big problem,” he told TheBlaze. “In all industries, you find children in forced labor — from agriculture, tea estates, fishing, flower farms, construction, coffee, mining and quarries. Sex trafficking of minors is also widespread across Kenya, but the biggest area for it is on the coastal strip where children are being sold to foreign sex tourists.”

“We at HAART think the most common form of child trafficking is domestic servitude,” Christensen continued. “This is based on the cases and stories we receive. It is widespread and in many cases, the traffickers are normal people who feel they are doing the child a favor by taking them in since they in many cases would come from impoverished [families].”

HAART’S goal in ending modern slavery — including that of women willingly going to the Middle East in search of work but being exploited in different ways — is through education. The organization targets vulnerable communities and hosts dozens of workshops each month, has published a guidebook for training of children in vulnerable areas or orphanages and partners with the Youth Career Initiative — a project that provides several months of job training in 5-star hotels for survivors of trafficking and other underprivileged youths.

“And yet, what is also needed is alternatives. Many times people will ask in our workshops, ‘Do you have any alternatives?’ The truth is that we don’t,” Christensen said. “There is massive unemployment or lack of jobs with fair wages in Kenya, so many are tempted to travel to the Middle East to look for alternatives. We have tried to address this in some very small ways, but it is far from adequate.”

And when it comes to young boys, Christensen said, the statistics are even worse.

He said:

We do work with some cases of boys being trafficked, but although we have a feeling that it is also a widespread problem, not that many cases are being reported. One possible explanation is that boys like men (who are also victims of trafficking) are culturally speaking supposed to be strong and and not show weakness. The cases are also widespread, it happens in different industries and also in domestic houses, although more often working in the garden than as domestic servants. Boys are also recruited into gangs and terrorist groups and other criminal activities.

Despite the work of nonprofits in the area and efforts by educators, not everyone recognizes the problem or even the possibility of trafficking in western Kenya. Anne Nambiro, who is running to be the women’s representative of Kakamega County — which includes Butere — told TheBlaze that trafficking isn’t a problem in the area. Instead, Nambiro argued, it’s more of an issue on the eastern coast of Kenya, which is overwhelmingly more Muslim.

Nambiro dismissed the idea of child trafficking posing a problem for Kakamega County during a brief interview with TheBlaze while on a campaign stop outside of Springs of Grace School where just hours before, Atsango discussed his initiatives to keep girls safe from agents or other men who have been known in the area to kidnap them off the streets.