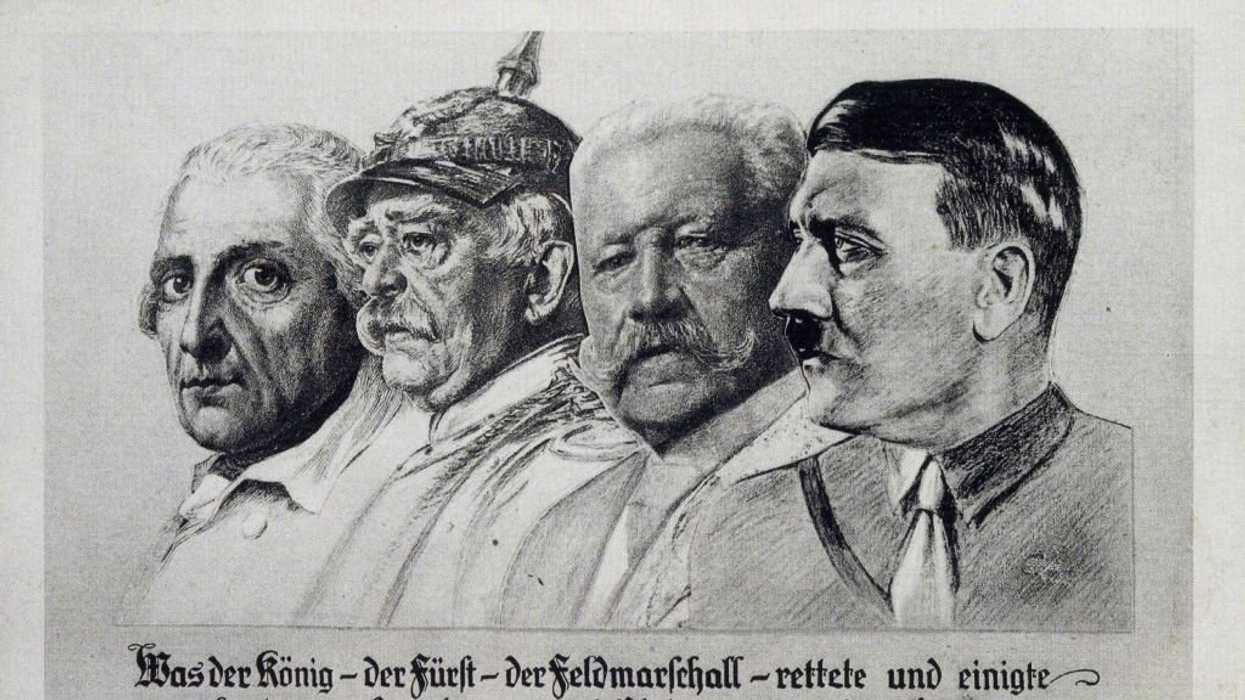

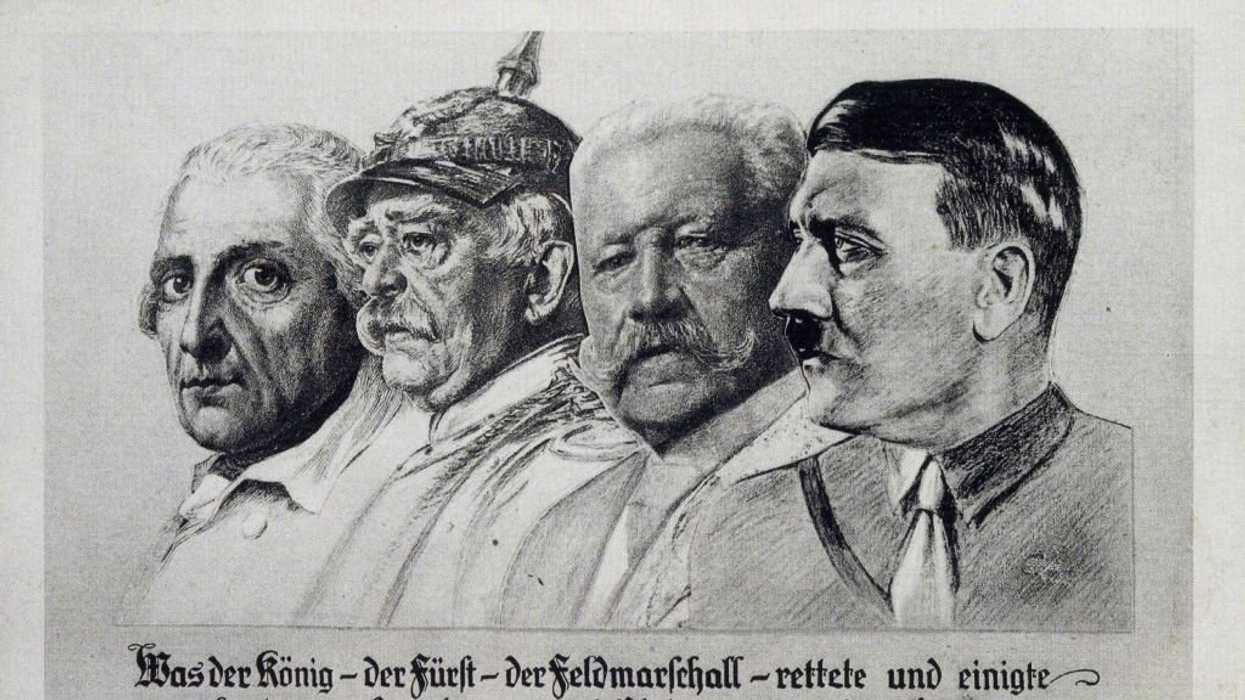

Photo 12/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

In recent decades, the underlying philosophy and practices in American universities have come to resemble their German autocratic and racist forebears of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Campus reactions to the invasion of Israel by Hamas on October 7, 2023, have shocked most observers, including those who recognized behavior terribly reminiscent of conduct at German universities during the 1930s. What happened to our universities, many Americans have come to wonder, that produced the anti-Semitic outbursts and similar thuggish behavior, along with the reluctance of university trustees, presidents, and faculty to condemn them? While many see the turning point in 1960s radicalism, the real turning point was the transformation of higher education in the decades following the American Civil War.

The United States was founded on the principle that all human beings have exclusive ownership of themselves, their liberty, and their property, with the government responsible only for their protection. The Revolutionary and Civil Wars were fought to defend these natural rights for all. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the faculty and leaders of the country’s colleges and universities agreed, teaching and hopefully inculcating these principles from one generation to the next. One example is Brown University’s anti-slavery president Francis Wayland, an uncompromising defender of natural rights and limited government. His textbook, “The Elements of Moral Science,” first published in 1835, sold more than 200,000 copies in the 19th century, according to the university.

Today, the typical institution of higher education has come to resemble a sectarian church, one whose doctrinal beliefs reject America’s philosophical origins.

That all began to change in the 1870s, when American colleges decided to transform themselves into replicas of German universities, which were widely viewed as the most advanced institutions of higher education in the world. In mathematics, the empirical sciences, and medicine, they undoubtedly were. The social sciences and humanities were morally and empirically inferior to their American counterparts, however.

German professors and administrators considered themselves — and, in fact, were — arms of the state. They viewed citizens as having no “natural” (that is, pre-legal) rights in the American understanding of that term — only government-granted privileges and obligations to obey political superiors.

These statist doctrines were taught to the many hundreds of Americans who studied in German universities and, having returned to the United States, were determined to instill them here.

By the end of the 19th century, the concepts of natural rights and liberties and the government’s limited role in protecting them were explicitly repudiated by leaders of the country’s social science and humanities professoriate. Describing the consensus among his academic peers in 1903, Charles Edward Merriam, who founded of the political science department at the University of Chicago, wrote that the “individualistic ideas of the ‘natural right’ school of political theory” have been “discredited and repudiated.” Instead, he quoted John W. Burgess, founder of Columbia University’s doctoral program, who wrote: “The state is the source of individual liberty.”

The first German-trained Americans and their students understood that characterizing themselves as their teachers did — that is, as state socialists — was a nonstarter. Instead, they borrowed the name “Progressive” from the German Progress Party, a pleasing term that allowed them to avoid fully describing their views, especially in public.

After World War I, when Germany had become anathema to many Americans, the Progressives adopted a new self-description: Liberals. When New Dealers adopted that term for themselves, the famous, formerly Progressive columnist Walter Lippmann more accurately described the New Deal as fascist in his book, “The Good Society,” shocking his former ideological brethren.

Over the decades, the underlying philosophy and practices in today’s American universities have eerily come to resemble their German autocratic and racist forbears of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Beginning in the 1950s, survey after survey confirmed that the typical American university had become a “one-party” campus with liberals outnumbering conservatives and libertarians by extraordinary percentages. For example, a 2016 study of faculty voter registration in 40 leading American universities in Economic Journal Watch reported that overall, 3,623 were registered Democrats and 314 were registered Republicans. The ratio of Democrats to Republicans in economics was 4.5 to 1, in history 33.5 to 1, in journalism 20 to 1, in law 8.6 to 1, and in psychology 17.4 to 1.

More recently, a 2022 study by the Harvard Crimson, the student newspaper, reported that 80% of the faculty of Arts and Sciences “characterized their political leanings as ‘liberal’ or ‘very liberal,’” while “only 1 percent of respondents stated they are ‘conservative,’ and no respondents identified as ‘very conservative.’”

Today, the typical institution of higher education has come to resemble a sectarian church, one whose doctrinal beliefs reject the country’s philosophical origins. With faculty having the exclusive power not only to train but to select their successors, students have assimilated the views of their teachers, transforming the media, constitutional law, and one of the two major political parties.

And yet, it was not as if no one warned the country.

In August 1883, Herbert Tuttle, Cornell University’s highly esteemed historian of Germany, wrote in the Atlantic Monthly about the Americans earning doctoral degrees in the social sciences at German universities and attaining appointments at U.S. universities. The theory of government they learned abroad, he explained, “assumes as postulates the ignorance of the individual and the omniscience of the government” — a government, moreover, “removed as far as possible from” the influence of elected legislatures and public opinion.

If America’s academic “pilgrims are faithful disciples of their masters,” Tuttle concluded, they will be “advocates of a political system, which, if adopted and literally carried out, would wholly change the spirit of our institutions, and destroy all that is oldest and noblest in our natural life.”

In Germany, this view of omniscient government had dominated universities since the early 19th century, leading ultimately to Nazism in the 20th. What political destiny does it hold for America?

Editor’s note: This article has been adapted from “Winning America’s Second Civil War,” published Tuesday by Encounter Books.

Jeffrey Paul