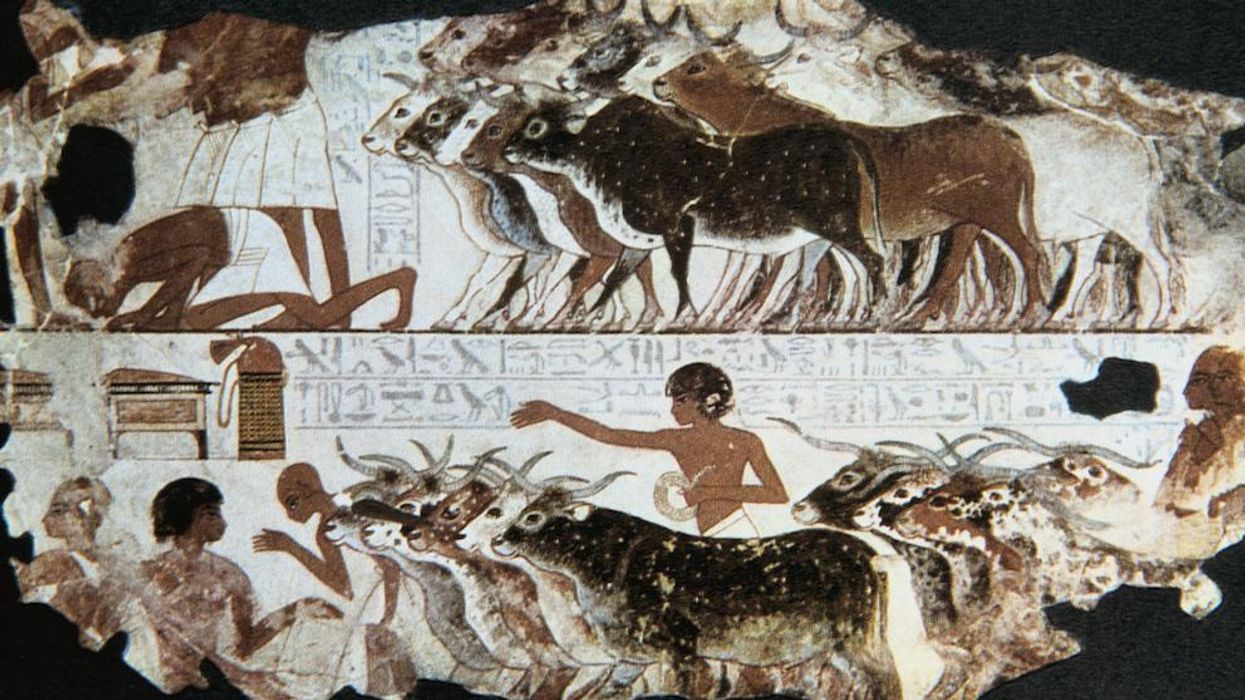

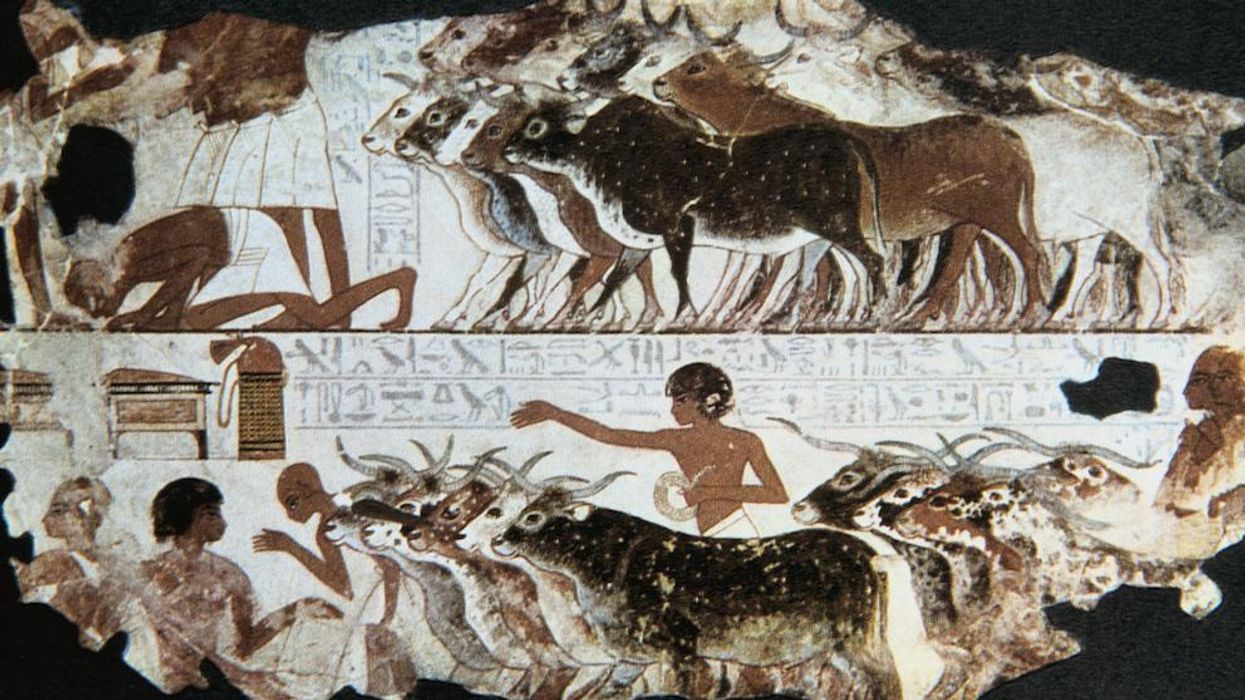

Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

Lewis Mumford’s love for architecture began when he was a boy, before he got tuberculosis, before he was drafted into the First World War, before he won the Presidential Medal of Freedom, before he became friends with Frank Lloyd Wright.

He used to go on walks with his grandfather through New York City every weekend. And he would dream about all the humans who came before us, all the lives and stories that had guided history to that very moment, as he gazed at the Manhattan skyline. He imagined utopias, some of which we currently live in.

Mumford held great optimism about technology. He saw it as a gift, the outcome of the goodness of humanity. He believed that, in and with and through technology, humans would continue to improve the world.

“Technology is in fact nothing other than a human action directed at a goal,” writes Martin Heidegger, it connects us to “the silent call of earth.”

But Mumford's greatest innovation was the idea that early humans succeeded because humans are spiritual beings, and that, for some reason, we are special. Everyone had always just assumed that the vector of history is determined by the speed of technology. That humans advance with every new invention.

And it is true, to an extent. But Mumford believed that creation of the tools was less important than the spiritual awakening that humans experienced.

Humans used tools and fire for at least a few hundred thousand years. Bones became crafting tools. Including paintbrushes — Paleolithic art spans a distance of almost 20,000 years. That’s four times longer than the history of modern civilization.

But, to Mumford, the greatest technology ever discovered is the human mind, the power of fascination.

The first tools that humans discovered were themselves. Their hands, their voice, their eyes, and their belief in something they didn’t understand.

It was a quiet sort of believing. It didn’t have a reason for existing. It didn’t come with any specific emotion, impulse, or urge. But it was there, never hiding, but also never front-and-center, a spirit, a power.

Mumford wrote in his book Technics and Human Development:

In the beginning was the act: meaningful behavior anticipated meaningful speech, and made it possible. But the only kind of act that could acquire a fresh meaning was one that was performed in company, shared with other members of the group, constantly repeated and thus perfected by repetition: in other words, the performance of a ritual.

Over time, humans repeated these performances.

Ritual connects us to our humanity, to ourselves and other people. It is an exercise in communion, a way to share meaning. It stabilizes life.

Ritual allows us to work through a crisis. And our world is a world in crisis.

Ritual unveils, it shows us what is sacred, guides us toward belief. For thousands of years, if something or someone was sacred, it meant that it did not belong to you. It belonged to God, to the ordering power of the universe.

“Religion is at the heart of every social system,” writes Rene Girard, "the true origin and original form of all institutions, the universal basis of human culture."

Hunter-gatherers weren’t grunting primitives wandering the vast plains. They were information machines, dumbly creating new worlds without really knowing why. Technological wonders, more incredible than Apollo 11.

In the Neolithic Era, humans became domesticated. The first domesticated animal on earth.

Domestication brought an important invention: the garden. And with it, the ax and the container. But something else happened.

Stand-alone shelters became villages. Settlements appeared in Syria, Greece, Estonia, China, Ireland. And shortly after, the first hint of politics emerged, with the democratic councils of elders.

That moment, when the elders gathered for the first time, launched humans into an entirely new technology: the technology of civilization, the rate of advancement always increasing, into architecture, comedy, art, and lots of war, which often determined the speed of technological advancement.

German political philosopher Hannah Arendt writes that the art of politics “teaches us how to bring forth what is great and radiant.”

She looks to the Ancient Greeks for a full understanding of what politics ought to be, and she arrives at the primacy of action and speech. The art of storytelling, through conversation and performance.

Human action survives through story. But it is the chorus, not the actors, who reveal a story’s meaning. The chorus tells, the actor imitates, and “the political realm rises directly out of acting together.”

Arendt positions freedom in cohesion with this plurality: “No man can be sovereign because not one man, but men, inhabit the earth.”

For Plato this spirit came to life as the polis, which roughly translates to "city" or “political community.” Aristotle writes that “the polis comes into existence for the sake of living, but remains in existence for the sake of living well."

Arendt is careful to point out that the nature of Ancient Greek political activity was much different than our own. For one, lawmakers were not part of the process.

Politics, instead, was the activity of the citizen. And the polis was a reliable place to be seen and heard, to have your story told. More than a fixed place, it was “the organization of the people as it arises out of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between people living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be.” When the people disbanded, power vanished, and when power vanished, the polis was gone.

About the time of the Enlightenment, people got cocky. They started to roll their eyes at ritual and belief. They started to replace God with themselves, with artists, with politicians. And they put their faith in reason instead.

“The true guide of human beings is not abstract reason but ritual,” writes Rene Girard. “It is religion that invented human culture.” Humanity is “the child of religion.”

The path from deism to atheism has been catastrophic for us as a species.

The consequences of our society of atheism have been nightmarish, almost terroristic. French psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva frames this as our era’s “nihilistic distress and its maniacal underside, fundamentalism.” Either extreme leads to the secularization of culture and the deprivation of its capacity for truth. This rejection catapults society into violence and automation, nihilism and emptiness, both of which lead to the negation of humanity, leaving the “raw wound of the need to believe.”

In all our advancements, we’ve abandoned ritual, the portal to the sacred, the soul of religion.

Yet even Freud, who claimed to fight religion, believed in a higher truth. “Logos God,” he called it. The Word of God at the very beginning. It was one of the few topics that made him squirm, because it felt so enormous.

“Imponderable,” is the word he used.

It gave him a feeling. He said this feeling was as an enormity, as big as an ocean. Something that comes over you, and you know, you believe, and you may not have words for it, but it still speaks.

When you hear the word “Freud,” the word “mother” comes to mind. And not in a good way. But when Freud talked about the oceanic feeling, the word of God, he explained it as the truth we know while we’re still in the womb, before we realize there’s a difference between us and our mother, us and the world, before we realize there's a world of differentiations at all.

Our very first experience. No threats, no evil, no disappointments. Only the sound of our mother’s heartbeat in a world of warmth and certainty.

That place, that feeling, that truth, is all around us even now, we just tend not to notice.

But we get glimpses. Connections. The feeling.

We aren’t in a village, with the council of elders, or in a city as a member of the polis. We’re separated, distant. These words are spiraling to you through code and screen. But our connection is as strong as this way of connecting ever was. And by remembering it, by continuing the ritual, by believing, we can find strength, in God, in life itself. We can correct course and land on our feet.

What's Heaven without the Earth below it?

We don't know, but we know. We’ve been taught to champion the Socrates slogan, “All I know is that I know nothing at all.” But who actually believes that? Who — in this era of convenience and transparency and fame — actually feels tinier than the stars?

We see the Manhattan skyline and it reminds us that God sings every morning. That breath, that entirety, must have been our first inspiration.

Susanne K Langer writes, “the symbols that embody basic ideas of life and death, of man and the world, are naturally sacred.” Humans have always observed these symbols through performance, the rituals that founded human culture, lifted into “symbolic transformation of experiences that no other medium can adequately express.”

Ritual is an expression of rhythm, as defined by Bifo Berardi, it is “the vibration of the world,” and rhythm is “the inmost vibration of the cosmos,” “the mental elaboration of time, the common code that links time perception and time projection.”

It’s two lips directing a voice, exhaling a song, a shout on the street. It’s geese across the horizon, dust from construction, the stink of oil, horses clopping, all the miniaturizations of life we don’t see.

Check out Kevin's Twitter. Send all notes, tips, corrections to kryan@blazemedia.com