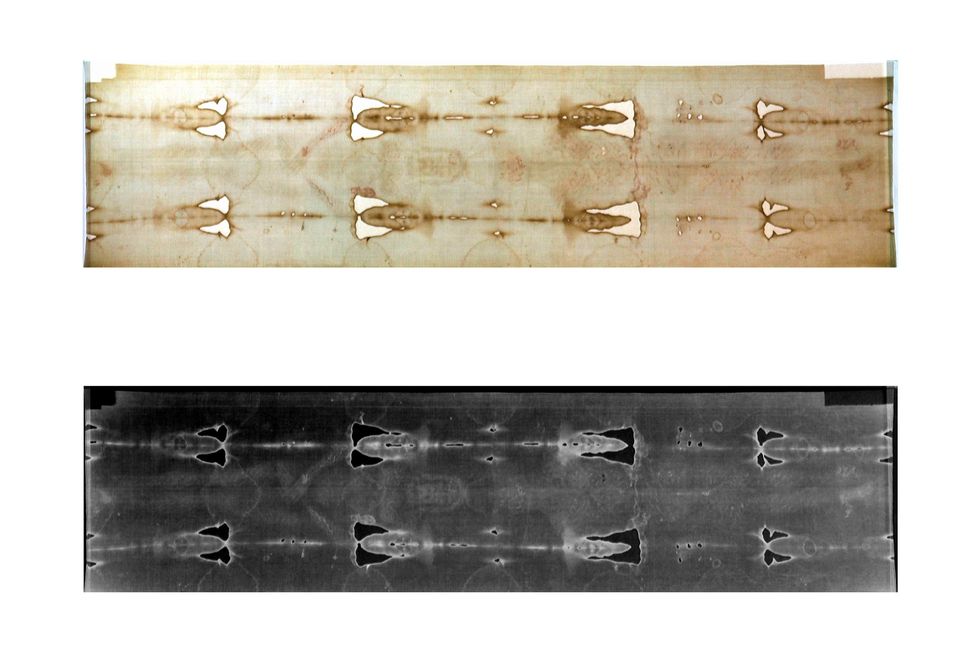

Stefano Guidi/Getty Images

The media loves a good 'gotcha' moment. Too bad this one collapses under the weight of real evidence.

Once again, the Shroud of Turin is making headlines, this time with bold claims such as “The Shroud of Turin was not laid on Jesus’ body, scientists reveal” and “Shroud of Turin didn’t wrap Jesus’ crucified body — it was just art, new research claims.”

These sensationalized assertions are based on a recent article published in Archaeometry, in which Cicero Moraes, an accomplished digital modeler, used visually intriguing 3D simulations to argue that the Shroud image could not have been formed on a full human body, but rather by contact with a low-relief sculpture.

Why wouldn’t Jesus leave behind a sign of His resurrection?

While the media delights in a provocative “debunking” narrative, Moraes’ study is not a scientific breakthrough. In fact, it recycles long-discredited assumptions.

His central thesis — that the Shroud is a contact imprint — is not demonstrated but simply presumed. Using 3D software, he simulates what a cloth might look like when draped over both a full 3D form and a shallow bas-relief. He then concludes — predictably — that the bas-relief result more closely resembles the Shroud. But this is not new insight. It’s a tautology.

When you begin with a flawed assumption, your conclusion naturally mirrors it. This isn’t discovery — it’s circular logic.

More importantly, Moraes fails to engage with decades of rigorous image analysis and physical testing that demonstrate the Shroud image is not consistent with contact imprinting, artistic rendering, or any known medieval method. The Shroud’s image is anatomically precise, encoded with three-dimensional information, and limited to the topmost surface fibrils of the linen — not soaked or pressed through as one would expect from a contact transfer.

Moreover, Moraes’ approach ignores decades of serious scientific work, especially findings that deeply challenge any contact-based theory. The Shroud image is not the product of direct contact. It is far too subtle, too topographically accurate, and too spatially encoded for that.

Last week, I had the privilege of serving as a keynote speaker at the International Shroud of Turin Conference in St. Louis, where I met with Dr. John Jackson, one of the original physicists who led the 1978 STURP investigation and co-author of the landmark 1984 Applied Optics study on image formation.

The evidence he and his team uncovered stands in sharp contrast to the assumptions Moraes recycles.

Consider the groundbreaking VP-8 Image Analyzer work done in 1976 by Captains (and physicists) John Jackson and Eric Jumper, U.S. Air Force scientists. This analog image analysis device, developed for nuclear weapons laboratories in New Mexico, was designed to detect spatial relationships in radiographic imagery. Additionally, the VP-8 Image Analyzer was developed and used by U.S. military weapons laboratories, specifically for analyzing high-energy radiographic and photographic data, including images of atomic bomb tests.

When Jackson and Jumper input a photograph of the Shroud into the VP-8, the machine generated a three-dimensional relief of a human body.

RELATED: Is the Shroud of Turin legit? Here's one pastor's interesting take

This was extraordinary. No other photograph — whether of a painting, statue, or live subject — produced anything close. Why? Because the Shroud image is spatially encoded. Its image intensity varies inversely with the distance between the cloth and the body it once covered. The closer a body part was to the cloth, the darker the image; the farther away, the fainter the impression.

This inverse relationship was confirmed in Jackson, Jumper, and Ercoline’s 1984 peer-reviewed paper in Applied Optics, where they wrote:

The frontal image on the Shroud of Turin is shown to be consistent with a body shape covered with a naturally draping cloth in the sense that image shading can be derived from a single global mapping function of distance between these two surfaces.

They concluded that none of the known artistic or physical processes — direct contact, heat transfer, dabbing with powders, electrostatic imaging, or radiation from a heated bas-relief — could simultaneously explain the Shroud’s 3D encoding, high resolution, surface-only image penetration, and absence of pigment or thermal damage.

Let me be clear: The Shroud is not simply a medieval art piece or a contact imprint.

Its image resides only on the topmost fibrils of the linen’s surface. It does not penetrate the threads. Its subtle optical qualities are consistent across ultraviolet and visible spectra. It displays anatomical fidelity that would be nearly impossible to reproduce by hand. And unlike thermal burns from the 1532 fire, which fluoresce under ultraviolet light, the image does not, indicating it was not formed by heat.

Moraes’ theory also fails to explain the lack of distortion.

As Russ Breault noted in his interview with Michael Patrick Shiels, a cloth wrapped around a face would, when flattened, appear “like a pumpkin.” Yet the Shroud image displays no such warping. The image appears vertically collimated — not distorted or stretched as it would be from wrapping or contact.

And critically, attempts to reproduce the image by pressing cloth against bas-reliefs or models — whether by rubbing pigment, applying heat, or using other methods — have consistently failed to replicate the Shroud’s anatomical accuracy or 3D encoding.

As Jackson and his co-authors emphasize:

A satisfactory hypothesis of image formation must be able to produce an image structure capable of a 3-D interpretation … for in doing so the shading distribution of the Shroud image should presumably be duplicatable.

So what are we left with?

While Moraes’ graphics are state of the art, the conclusions drawn are far less innovative than they first appear. The study rests on a foundational assumption: that the Shroud image is a type of contact imprint — essentially, a “body print” resulting from direct physical interaction with a corpse or sculpted form.

Unsurprisingly, Moraes’ simulations conclude that a low-relief model aligns more closely with the Shroud image than a full-body figure. But as digital artist Ray Downing — a renowned American 3D expert who was featured in the History Channel special "The Real Face of Jesus" — rightly observes, this is a classic case of circular reasoning. If one begins with the assumption that the image was formed through contact, it is no surprise when the model supports that assumption.

This approach overlooks critical empirical details. The Shroud image is characterized by its photorealistic subtlety, with gradations and shading more akin to a negative photographic plate than a physical transfer. Traditional contact imprints, by contrast, produce stark, binary images — high in contrast, low in nuance.

But the presence of features such as the sides of the nose and cheeks — areas unlikely to have touched the cloth at all — poses a serious challenge to any purely contact-based model.

RELATED: New evidence indicates Shroud of Turin shows EXACT moment of resurrection

There are further inconsistencies.

The lack of mirror symmetry between the frontal and dorsal images contradicts expectations from simple cloth-body interaction. We also do not observe the telltale signs of capillary wicking or pressure distortion typical of contact imprints. Moreover, the bloodstains on the Shroud are anatomically precise, appear to have transferred at a different time from the body image, and exhibit halo rings under UV fluorescence — further evidence that the blood and image formed by distinct mechanisms.

As Downing and others have noted, Moraes’ study does not provide novel insights beyond what has already been established — decades ago — by the STURP investigation. His use of modern rendering software offers a visual upgrade but does not advance the scientific conversation. Presentation alone cannot rescue a flawed hypothesis.

Ultimately, Moraes’ work illustrates a broader truth: Technological sophistication cannot compensate for weak foundational assumptions.

Until a contact-imprint model can be demonstrated under real-world conditions — and account for the full range of physical, chemical, and optical properties of the Shroud — the theory remains speculative at best. Digital simulations, no matter how elegant, are only as reliable as the premises they’re built upon. In this case, the digital artistry is commendable, but the interpretive framework remains deeply inadequate.

Moraes’ simulation, while technically polished, brings nothing new to the conversation. It recycles a theory that fails against the hard evidence — evidence amassed by physicists, chemists, and image analysts across more than four decades. Without accounting for the VP-8 findings or the full chemical, spectral, and physical properties of the Shroud image, his conclusions remain, at best, superficial.

And then there’s the deeper question. As Russ Breault beautifully summarized: Why wouldn’t Jesus leave behind a sign of His resurrection?

According to John’s Gospel, the linen cloths left in the tomb were the first piece of evidence to convince John that Jesus had risen (John 20:8). Is it so implausible that God, in a moment of divine transformation, impressed upon burial linen a subtle, encoded image — a kind of sacred relic left for the world to ponder?

Moraes’ paper may impress in terms of digital technique, but it fails to contend with the depth of the data. Any theory about the Shroud must explain not just what is seen — but how it is scientifically seen.

The Shroud is not merely mysterious — it is measurable. And the more we measure, the more it challenges every naturalistic explanation offered so far.

Jeremiah J. Johnston