Nina Power

The sceptred isle has forgotten itself, but its people have not.

The banks of the Thames are clouded! the ancient porches of Albion are

Darken’d! they are drawn thro’ unbounded space, scatter’d upon

The Void in incoherent despair! Cambridge & Oxford & London,

Are driven among the starry Wheels, rent away and dissipated,

In Chasms & Abysses of sorrow, enlarg’d without dimension, terrible

Albions mountains run with blood, the cries of war & of tumult

Resound into the unbounded night, every Human perfection

Of mountain & river & city, are small & wither’d & darken’d

Cam isa little stream! Ely is almost swallowd up!

Lincoln & Norwich stand trembling on the brink of Udan-Adan!

Wales and Scotland shrink themselves to the west and to the north!

Mourning for fear of the warriors in the Vale of Entuthon-Benython

Jerusalem is scatterd abroad like a cloud of smoke thro’ non-entity:

Moab & Ammon & Amalek & Canaan & Egypt & Aram

Recieve her little-ones for sacrifices and the delights of cruelty

From Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Great Albion (1804-1820) by William Blake

It would be too easy to despair. Great Britain—the first civilization to industrialize, making spectacular and rapid use of coal and iron and the minds of its great engineers and inventors—seems to have woken up in the middle of a bad dream. Governed by a venal and malicious elite who would rather be in Davos than defending the native population, we have become a nation where farmers commit suicide in the face of inheritance tax raids, and where stating the obvious about sexual difference or the downsides of mass immigration will see you, if you’re lucky, unemployed and socially shunned, and, if you’re unlucky, charged with one of the myriad “hate crimes” that the police spend their time investigating while violent crime goes lightly punished, if at all.

We see Americans shaking their heads that we ever gave up, bar antique firearms and muzzleloaders, our guns—and they have a point. They worry that the country they remember, both in reality and in their imagination—the countryside, with its lambs and faeries and prehistoric megaliths and burial mounds, our millennia of great kings and queens, our pantheon of playwrights and poets—has all but disappeared, transformed beyond recognition by rapid waves of immigration and an apparent diminution in the spirit of this great people. “Wake up!" another meme has it, a lion sleeping on his side as a little boy pleads for the great flag-draped beast to roar again...

For all the internal schisms and external damage done to the faith, the reminder that, above all, Britain is a Christian country, does not, cannot, leave me.

American friends are rightly concerned, but for every doomy “England has fallen” post from across the seas, there is a rapidly growing feeling here that things can’t go on, and that we’re not going to let them do so. The veil has been torn, and reality is pouring in. Operation Raise the Colours, barely a couple of months old, where patriots across the land have spontaneously organized to hoist the St. George’s flag and the Union flag, is both a declaration and a warning: Albion will not go down without a fight.

I’ve lived in this country all my life, and I love everything about it. The appalling decisions made against the will of the people by a seemingly interminably evil cabal can be overturned. Meanwhile, the omnipresent chirp of hacked hire bikes and the feral screams of foxes and ill-managed children provide the soundtrack to a city in a state of permanent low-level suspicion. Cheap blue plastic bags from markets selling over-ripe vegetables and halal meat hang from trees like inedible futuristic fruit, while drug dealers openly hustle in parks (one might ruefully reflect that some of the country’s once great commercial energy remains).

Like many European nations, the United Kingdom—England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland—exhibits many of the hallmarks of decline: a stagnant economy, with almost a quarter of the population in receipt of benefits; omnipresent petty crime—phone theft, shoplifting—met with police indifference; and a rapid decline in the manners and customs that hold a people together. A British person born in 1961 London has, in the intervening decades, overseen his city transform from one that was 95 percent populated by men and women like him to a mere 39 percent. People have forgotten (or never knew) how to queue, and headphoneless TikToks blare out of phones on public transport. The little scripts of civility that subtend a conscientious, high-trust society are quickly vanishing, and in its place a more brusque, edgy, and hectic energy prevails. In the poorer streets of London, one has the feeling of wandering through a years-long carnival that has forgotten to end.

And the lion may be taking its time, but England will rise again: we must with prayer and force, to vanquish those who wish us ill and to protect everything we hold dear.

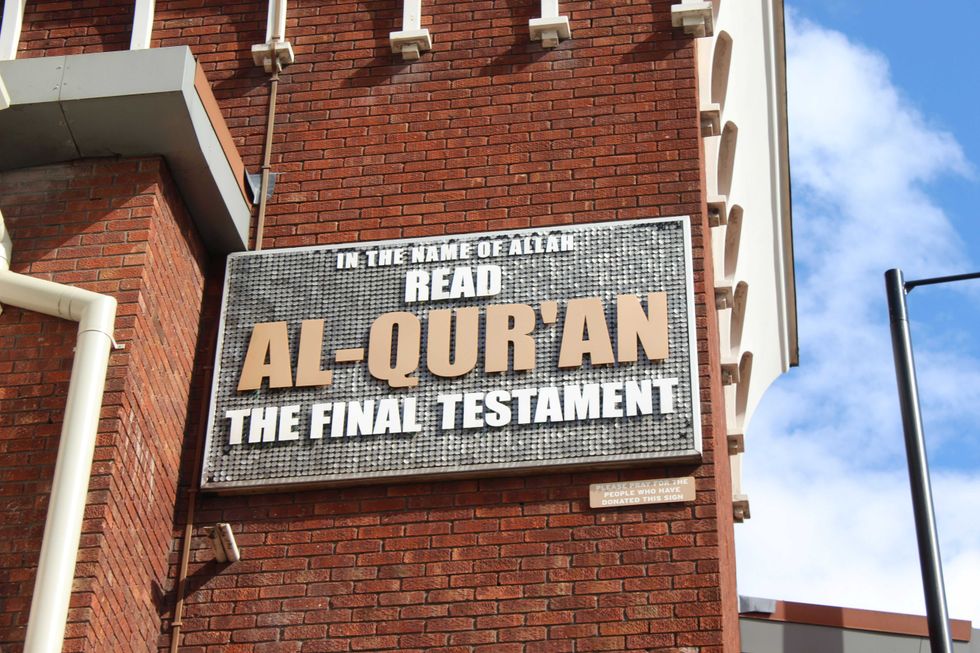

The United Kingdom is now “the Yookay,” a designator coined by the pseudonymous X poster Drukpa Kunley, who regularly posts elaborate and scathing memes concerning our national degradation. The Yookay is comprised of a chaos of nationalities—almost 20 percent of England and Wales were not born here, according to the 2021 census, but it’s not clear that anyone actually knows the true figure: leading supermarket Tesco reckons it’s more based on sales of staples, and the sewage companies have reported more effluence than our near 70 million “official” population might be expected to produce. Britain now hosts around 1,500 mosques, and it is not unusual to see stalls proselytizing on behalf of Islam, though Christians praying at abortion clinics are routinely arrested, as JD Vance has noted. In London, apart from the rich, who dwell in a fantasy of the old city, most live in religious and ethnic mixed areas, but some parts of England are now dominated by Islam alone.

I was recently in Birmingham for an annual event called “The Witan,” named after the seventh–eleventh-century king’s council, where wise and noble men gathered to advise the monarch on matters of war, money, and policy. Although King Charles III was absent, leading lights on the British Right—Christian and non-Christian alike—as well as a smattering of international speakers, came together to discuss politics, heritage, and culture (there was much mention of J.R.R. Tolkien in particular.)

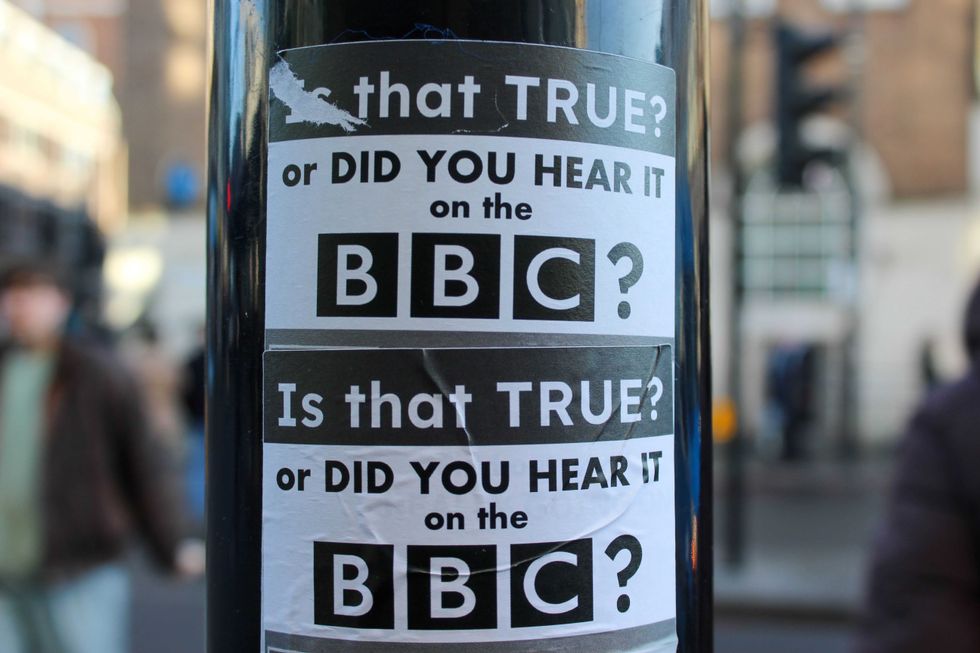

Britain’s second-largest city became minority white as of the 2021 census, with 17 percent of the city’s population from a single foreign country—Pakistan. American readers might know, largely as a consequence of Elon Musk’s attention to the horrible story, that 50 or so cities in the UK have been host to so-called “grooming gangs” (or rape gangs). Many of the men involved in these terrible acts are Pakistani, and they explicitly targeted young, white, often vulnerable working-class girls, plying them with alcohol and drugs and systematically abusing them over years, and at scale, among groups of men. In many cases, the girls were disbelieved and even punished by the authorities, and described as “child prostitutes” by the BBC, implying that the girls were somehow to blame for their unimaginably horrific treatment. Many in the police and left-wing Labour councils knew about the abuse. They were complicit in it, sacrificing the girls in the name of our new alien gods “multiculturalism” and “community relations.” Some of these gangs were based in and around the West Midlands, where Pakistanis and other populations were forcibly imposed upon poor and working-class whites.

Before the conference began, I spent a few hours walking around the vast Muslim-dominated areas of the city—particularly Sparkhill, notorious for a 2005 riot between Pakistanis and Caribbeans, after an alleged gang rape of a black teenage girl by Pakistani men. Moazzam Begg—extraordinarily renditioned to Guantanamo Bay on account of his Al-Qaeda membership—was born here.

Sparkhill was described as a “no-go area” last year by a Conservative MP, and I was curious to see whether it lived up to its less than flattering reputation. Wearing a modest dress with my camera around my neck, I encountered a few hostile stares, often from young men in cars, but no outright confrontation. What struck me, apart from how large and exceedingly un-English the area felt, as well as the appalling driving and parking, was the relentless mess.

Near the Central Mosque, illegally dumped sofas, burnt plastic, and domestic detritus covered the pavement. Palestinian flags flutter over disused tires, abandoned car seats, and shopping carts.

The city has lately become synonymous with litter, cat-sized rats, and the fear of disease. Since March, Birmingham refuse workers have been on strike, complaining of proposed pay cuts and cuts to officer roles. Nevertheless, despite 17,000 tons of uncollected garbage building up, other parts of the city have managed to stay tidy. Not so in Sparkhill, where, even near the Central Mosque, illegally dumped sofas, burnt plastic, and domestic detritus covered the pavement. Palestinian flags flutter over disused tires, abandoned car seats, and shopping carts. Children’s play areas are festooned with empty takeout cartons and plastic bags. There is no future here.

Back to the Witan and, under the baroque beauty of the ballroom ceiling of the newly restored Grand Hotel, a largely male and rather young crowd discussed everything from birth rates to Chinese history, Anglofuturism to David Lynch. The atmosphere was optimistic and dynamic. I talked about how Britain was both a pagan and a Christian country, and the ways in which cremation and other “modernizing” technologies, such as television and the internet, had cut us off from our ancestors and heritage: how many of us even know where the graves of our forebears might be found?

In this vein, a panel by the newly formed Pendragon Foundation (“New Visions for Castles”) was particularly striking: following the success of a French initiative that raised millions of euros to save ailing Chateaux, the group are already working on the reconstruction of several of Britain’s ancient strongholds. One is so used to imagining that such castles and keeps must by default belong to one of the two major British charities, the National Trust and English Heritage, that one forgets there are castles outside of their reach, often in need of serious restoration (the Pendragon Foundation members noted too that many properties managed by the charities will be coming up for sale as they are, like many other institutions, running out of cash). Others talk of buying up dilapidated churches before the Muslim Brotherhood gets to them first.

At the Witan, a positive and historic vision of Britain emerges: a country battered by poor and venal governance, but still teeming with life, and people with the wit and energy to restore with care and archival knowledge, the great outposts that remain. Ruins too have a spirit. One speaker referred to Britain as an American satrapy, and others spoke of a revitalized Europe: not, to be clear, of the Europe we attempted to escape, the bureaucratic super-federation, but of an older spirit than animates the different nations of the beleaguered continent. There is a government-in-waiting here, among the tweed and whisky and tobacco. Our discussions about paganism and Christianity will perhaps have to wait for a less febrile time, but they are at the heart of what we are all fighting for.

Britain is a Christian country that has forgotten about God. Our pre-Christian pagan roots are similarly obscured under the dead weight of distance and the accusation of LARPing, occultism, or eco-fascism anytime anyone tries to take heritage and nature seriously. But despite the best efforts of the Reformation and the liberal individualist malaise that followed it, Catholics have never left the island. In 2021, just over 8 percent of the English and Welsh population described themselves as Catholic (it’s much higher in Northern Ireland, naturally, at around 45 percent).

The Latin Mass Society, founded in 1965, is committed to the traditional Latin liturgy (the Tridentine Mass), which Vatican II superseded and which was further restricted under Pope Francis, who described it as indietrismo (“backwards” or “nostalgic”). Once a year, the society organizes a pilgrimage of around 60 miles over three days from Ely to Walsingham, a village in North Norfolk, where the Shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham was established in 1061, destroyed in the Reformation, and rebuilt in the late 19th century. This year, I joined over 200 people in a walking prayer for the conversion of England. Accompanied by crosses dedicated to Catholic martyrs, national flags, and the absolute devotion of the pilgrims themselves, who sing, pray the rosary, and listen to peripatetic sermons over much-needed sandwiches, this was a stunning reminder of the religiosity of those for whom faith is not merely attending church on a Sunday but an entire modus vivendi. A lengthy traveling daily mass took place every morning before even hot water was permitted, some on their knees for more than an hour, while chefs prepared vast pots of porridge. Despite the distinct lack of comfort—camping in rugby fields, sharing extremely small numbers of toilets, no showers—I didn’t hear a single complaint. I don’t think I’ve ever had a less modern experience, nor such a profound encounter with faith.

Others talk of buying up dilapidated churches before the Muslim Brotherhood gets to them first.

We walked for miles every day, through fens and forests and winding roads, in chapters led by cantors and accompanied by priests in gray robes, who live completely in the light of God’s providence, carrying only a Bible and a cross, feet calloused in old-fashioned leather sandals. They would sleep outside unless we offered them a tent, one fellow pilgrim tells me, and they only eat when there are leftovers. I don’t speak to the men to find out if this is true, as their holiness somehow creates an unapproachable aura, though I can see that they’re really quite friendly and light-hearted.

I’m struck by the number of dead animals—foxes, hedgehogs, birds—we see killed by cars and mangled by the side of the road. At one point on the second day, a beautiful young woman in my chapter came across a dying owl in the forest. Picking it up, she cradled it in her arms for the next few miles as we continued our walk, and the beautiful creature slowly breathed its last. I can’t think about the girl and the owl without tearing up, and this combination of sorrow and gentleness encapsulated something tragically and beautifully mysterious about the whole event: around 40 miles in, as my feet blistered and rubbed, a thought came to me: suffering is energy. Trance-like, we arrived at the ruins of Walsingham abbey, destroyed and looted in 1538, its incredible arch all that remains. We walked the last mile barefoot through rough track and village road. I surprised myself by managing the last half-mile, quickly learning to avoid sharp-looking rocks and broken glass. For all the internal schisms and external damage done to the faith, the reminder that, above all, Britain is a Christian country, does not, cannot, leave me.

The lion, symbol of 12th-century Norman kings, and, in its Christian incarnation, in C.S. Lewis’s Aslan, as a symbol of Christ, is an anachronistic symbol for England—particularly as any real cave lions that once roamed the land died out between 12,000 and 14,000 years ago—but the lion represents everything profound about the country: nobility, pride, and a quiet but deadly strength. As Wallace Stevens wrote in his mid-1950s poem, “Poetry Is A Destructive Force”:

The lion sleeps in the sun

Its nose is on its paws

It can kill a man.

We may have little sun—although the past summer has been unusually glorious—and the lion may be taking its time, but England will rise again: We must, with prayer and force, in order to vanquish those who wish us ill and in order to protect everything we hold dear. We may be, as George Orwell once put it, “a family with the wrong members in control,” but a great reordering and restoring is possible, and urgently needed.

Nina Power