Sian Roper

The slow, tragic death of the American Dream was on full display at the Grateful Dead's 60th anniversary in San Francisco.

It was unclear if the man in the stars and stripes onesie was passed out drunk, tripping on acid, napping, or dead. He lay perfectly still in the Polo Grounds in Golden Gate Park as the furious guitar picking of bluegrass wunderkind Billy Strings blared from the stack of speakers 100 feet to the man’s left. No one seemed to notice or care. The Dead they were concerned with were about to take the stage.

“Are the Dead nationalist?” my friend Melody asked me, clocking the recumbent man in the flag-colored pajamas. It was her first time seeing this or any incarnation of the Grateful Dead, the 1960s roots rock band that would go on to become a singular, revolutionary force in American music history. The band, now performing as Dead & Co. with John Mayer on lead guitar and vocals, was celebrating its 60th anniversary in its city of origin, and Melody was struck by the sheer amount of patriotic iconography on display.

All throughout the crowd were Deadheads decked out in red, white, and blue, oftentimes in tie-dye (of course). American flag-inspired visuals flashed across the stage’s enormous LED screens. Uncle Sam hats bounced above the throng. Three men donned blue blazers and red and white-striped pants—the full Brother Jonathan ensemble.

There’s a long-standing debate over which is the greatest American rock band. Rock and roll purists might argue the Beach Boys, citing their trove of hits about California sunshine. A similar case can be made for Creedence Clearwater Revival, who bewitchingly channeled the American South. Rock snobs love to claim it’s the Velvet Underground because of their outsized influence on the genre; avant garde ambient musician and legendary rock producer Brian Eno once said The Velvet Underground sold only 30,000 albums, but everyone who bought one started a band. There’s even a strong argument to be made for Nirvana, though their success, like their frontman, was relatively short-lived.

Instead of thoughtful, heart-wrenching, life-affirming art, we will have an infinite torrent of ephemeral slop—produced in just a moment and forgotten just as quickly.

But the Grateful Dead are the most American rock band. Their music alchemizes a smattering of uniquely American genres—blues, folk, jazz, bluegrass, funk, R&B, and good ol’ fashioned rock and roll—into improvised orchestral compositions so distinct that they pioneered a new genre, jam band music, that lives on with Phish, Widespread Panic, and the Dave Matthews Band. Their lyrics tell of a storybook American landscape filled with swindlers, vagabonds, folk heroes, charming drunks, dangerous women, and angelic beauties. Like America itself, the Grateful Dead is both welcoming and insular—the band is infused with lore, about which Deadheads love to flex their encyclopedic knowledge. The original Dead members espoused an anti-authoritarian populism that appeals to both the Left and the Right. It’s easy to imagine former Democratic senator Al Franken and right-wing firebrand Tucker Carlson barking at each other in a cable news segment, but it’s equally plausible to see them grooving together to an extended “Althea” jam. They’re both Deadheads.

More than all that, the Dead embodied America’s pioneering ideal: the revolutionary, the cowboy, the hippie—the untameable rogue who defies convention and refuses to conform, living life entirely on his terms.

And yet, 60 years after their founding, despite the band’s incessant protesting otherwise, that dream has faded away. The America on offer at Golden Gate that weekend in August was one of crass consumerism—comically expensive ticket prices that rivaled Coachella and thousand dollar luxury viewing suites. Much like the American Dream itself, the Grateful Dead’s founding ethos has withered and been forgotten, replaced with a lifeless exercise in conspicuous consumption.

My curiosity got the better of me, and I approached the supine man on the Polo Grounds grass when he suddenly lurched up and swiveled his head in a panic, assessing his surroundings. Just as quickly, he lay back down. Rather like his country, the man in the America jumpsuit was indeed alive, but perturbed and confused.

“How do these hippies afford this?!” Melody asked, pointing out items available for purchase at the merchandise tent. “Two hundred fifty dollars for a poster?!”

As was everything at the Dead’s three-day anniversary show, the merchandise prices were astronomical—T-shirts for $50, hoodies for $90, and a blanket for an even $100. Just to get into the event was wildly expensive—a three-day ticket cost $635, more than a three-day pass to Outside Lands, the multi-band musical festival held at the very same venue the following weekend. VIP packages cost more than $6,000, with the most expensive option nearly $10,000.

The most egregious prices, however, were at the food stalls. Forty dollars for a crab roll and fries. Dave’s Hot Chicken was selling a single chicken tender—just one, no fries included—for $30. The most reasonable lunch I could find was a $12 slice of pizza.

The irony could not be any more rich considering that the Dead, from their inception, were fiercely and proudly anti-commercial.

Like so many other mid-century American artists, Jerry Garcia, the late founder, leader, and emotional center of the Grateful Dead, was inspired by Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, the seminal Beat Generation novel about Kerouac’s vagabond travels across America. The Beatniks believed the seemingly idyllic life of post-war America—the middle manager position, the suburban home with a white picket fence, 2.5 kids and a wife in pearls and an apron—was a vapid lie. Their philosophy, the one Garcia and his bandmates later adopted, was that the most meaningful life was not lived in pursuit of wealth and career success but of connection, creativity, and experience. “We were always motivated by the possibility that we could have fun, big fun,” Garcia told Rolling Stone in 1993.

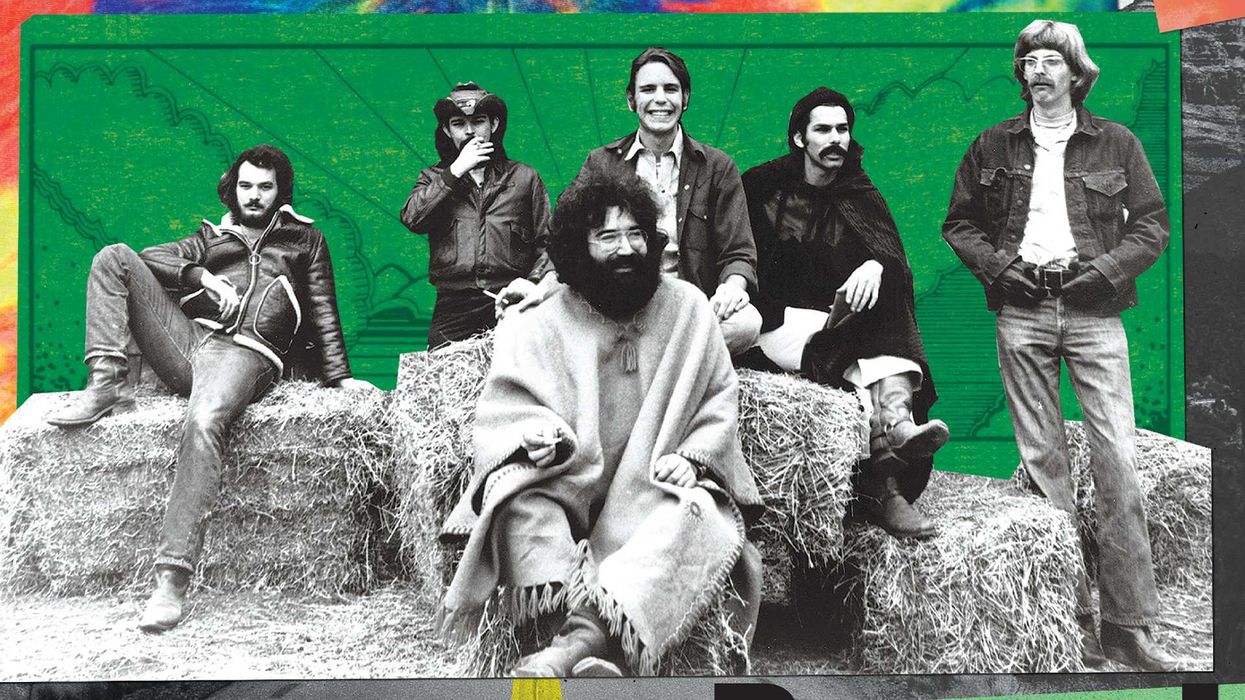

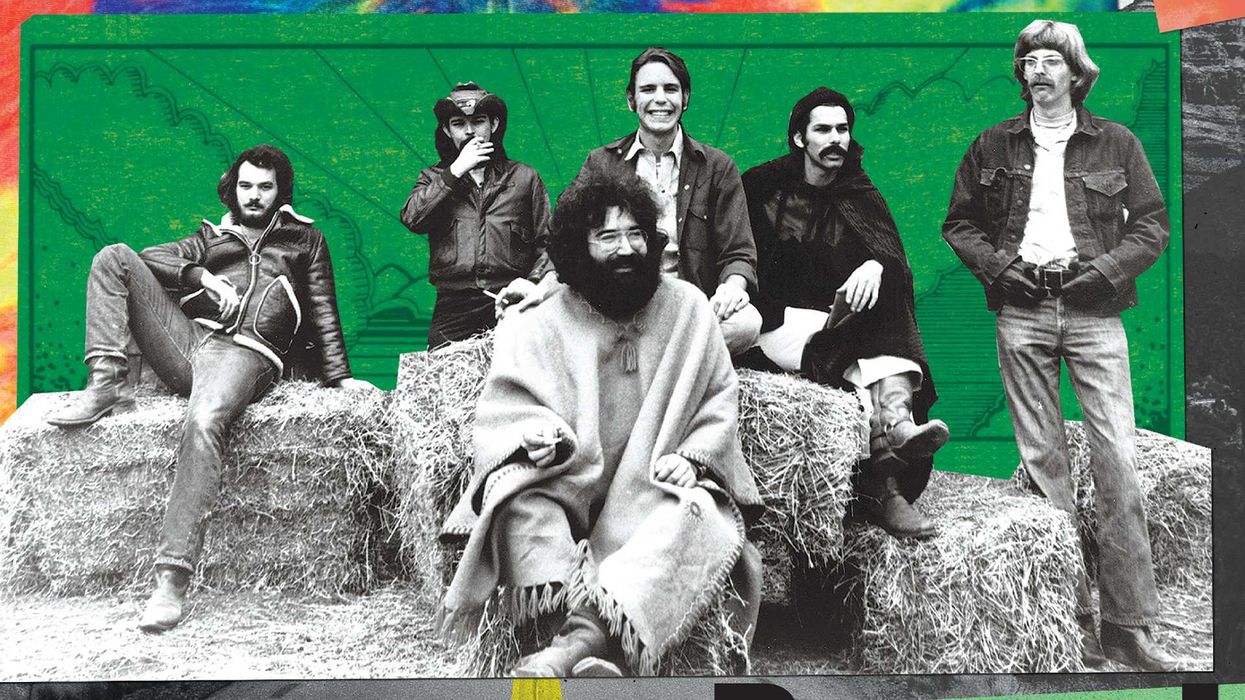

This was more than mere rhetoric. The Grateful Dead lived their values. Formed in 1965 in San Francisco, the Grateful Dead began playing acid-fueled house parties thrown by the Merry Pranksters, a group of hippies whose mission was to evangelize the mind-opening capabilities of LSD. (Neal Cassady, the inspiration for Dean Moriarty, the main character in On the Road, was one of them.) For the Dead, music was a vehicle to achieve a higher consciousness.

For this, the Dead were seen as synonymous with the hippie movement gripping San Francisco and then the nation at large. Corporate record labels were more than eager to commodify the counterculture and sell it back to Middle America. But the Dead showed zero interest in being a big commercial success. They lived in a group house, a Victorian in the city’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, and their only goal was to make enough money playing gigs to avoid getting day jobs. Warner Bros. signed the Grateful Dead anyway in 1966, and the band delighted in wasting the record label’s money.

Their lyrics tell of a storybook American landscape filled with swindlers, vagabonds, folk heroes and charming drunks; dangerous women and angelic beauties.

The band somehow negotiated unlimited studio time in their contract and treated all the fancy studio equipment like kids on Christmas morning. At one point, rhythm guitarist Bob Weir insisted the band record 30 minutes of “heavy air” on a smoggy day in Los Angeles and mix it with “clear air” from the desert, a request so absurd and impractical it caused the sound engineer to quit. Warner Bros. Vice President Joseph Smith tsk-tsk-ed the Grateful Dead in a 1967 letter to the band manager, writing that their studio sessions were “the most unreasonable project with which we have ever involved ourselves.”

The band’s fucking around in the studio left them $200,000 in debt to the label, prompting them at last to take the studio process seriously. The result was not one but two 1970 albums, American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead, filled with tidy, delightful blues- and folk-infused ditties, replete with melodies, harmonized vocals, and catchy hooks. Two of the songs, “Truckin’” and “Uncle John’s Band,” charted on the Billboard Hot 100.

The Dead proved themselves fully capable of recording artist success, and it would have been easy to ride the 1970s Laurel Canyon folk-rock wave, churn out an album a year, and print endless amounts of money.

But that’s not what the Grateful Dead was about. “We were never climbers in that sense,” Garcia said in a Classic Albums special about the making of American Beauty. “We were having fun doing what we were doing. We already knew it had almost no commercial potential, apart from the community we were in, and that was fine... The music we were making had some value to us and the world we lived in.”

Their music was meant to be heard live. No home listening could ever be a substitute for the magic of the live concert experience. Because the band relied so much on improvisation, no two Dead shows were remotely the same. The individual band members’ musicianship would spontaneously fuse into a towering sonic wave, blared from the Wall of Sound, the band’s towering PA system, to crash over the audience’s enfeebled minds. You had to be there to catch it.

The band toured relentlessly to bring their magic live to the people. At their height, the Grateful Dead played more than 100 shows per year. “We were a working band,” Phil Lesh, the original Dead bassist, who died in 2024, said of the group.

Yet, for much of their existence, the band was an underground phenomenon. The Dead inspired cultlike devotion among their small group of loyal fans, but the band didn’t achieve mainstream success until the mid-’80s, when the band suddenly and unwittingly transformed into a hit group among a new generation of counterculture youth. Fueled by “Touch of Grey,” the only top 10 hit of their career, the Grateful Dead surged in popularity, becoming one of the biggest bands in the world. For nine consecutive years, from 1987 to 1995, the Grateful Dead were one of the top five grossing acts in the country. Two of those years, 1991 and 1993, they were no. 1.

There were accusations of selling outback then, especially with the Jerry Garcia neckties and the Cherry Garcia Ben & Jerry’s ice cream flavor. But even as revenues soared, the band attempted, best they could, to stay true to their roots. The Grateful Dead never protected their copyright, allowing fans to create all kinds of bootleg merch. In 1995, when the band was making upwards of $50 million a year, Garcia was expected to clear only $300,000 after the spring tour. The band was famous for paying its production crew well. By the time of Garcia’s death, in August 1995, the extended Grateful Dead “family”—band members, managers, publicists, roadies, wives, girlfriends—had grown to the hundreds. A significant reason why Garcia worked himself into an early grave is he felt pressure to keep the family well-fed.

I don’t begrudge the surviving members of the Grateful Dead for cashing in; they paid their dues, and they’ve provided immeasurable joy to their fans over the decades. But I also don’t think Garcia would find the Coachella-fication of the Dead experience much “fun.”

“You’re getting a little tweaky,” I heard a Deadhead say to his girlfriend, right before the start of the third, and final, show of the weekend.

The woman had just taken a selfie huffing a balloon of nitrous oxide in front of the house the Dead rented when they formed the band. Now she was muttering incoherent gibberish to herself as other Deadhead devotees documented their pilgrimage to the Dead house with selfies of their own.

All along the walk into the Golden Gate Park, enterprising black teenagers sell nitrous balloons to affluent white concertgoers, off to see a band the teens have probably never heard of. Their world is one dominated by a vibe alien to Garcia and company. On the drive into San Francisco, I was bombarded with billboards for dozens of artificial intelligence startups with forgettable names and indistinguishable product offerings. “The #1 AI agent for customer service.” “Your app, Enterprise Ready.” Gamma, a startup that automates creating PowerPoint presentations.

The goal of these startups is to reduce human creativity to data and displace musicians, filmmakers, writers, and artists with generative content protocols. Their vision of the future does not include the next great American novel, a cinematic masterpiece, or a groundbreaking musical talent like the Grateful Dead. Instead of thoughtful, heart-wrenching, life-affirming art, we will have an infinite torrent of ephemeral slop—produced in just a moment and forgotten just as quickly.

At the concert, the band played “Standing on the Moon,” their most explicitly nationalist song. The tune is sung from the perspective of the American flag on the moon, marveling at Earth below.

I see the soldiers come and go

There’s a metal flag beside me

Someone planted long ago

Old Glory standing stiffly

Crimson, white, and indigo

The song reminds me of my father, who, at first glance, appears to be the furthest thing from a Dead-loving hippie. He worked a successful yet unglamorous job as a telecommunications salesman. He tucks his T-shirts into his cargo shorts and wears shin-high tube socks with clunky New Balance sneakers. He goes to bed at 8:00 p.m. His favorite hobby is gardening. But my stern, disciplinarian, hard-working father is also a devout Deadhead, having attended more than 70 shows across the band’s myriad ensembles.

My father and I listened to “Standing on the Moon” together on the Fourth of July 10 years ago at Soldier Field in Chicago, for what was billed as the Grateful Dead’s last concert. The Dead have, of course, continued to tour as the Mayer-led Dead & Co.—an effort that has been both derided as a money grab and hailed as a noble effort to keep the music alive. My dad likes to joke, “I’ve seen all five of the Dead’s final shows.”

Not only has the free-spirited, bohemian version of the American Dream died, but so has the middle-class alternative. I’m 37 years old, and by the time my father was my age, he had a wife, three kids, a steady career, and an affordable mortgage on a three-bedroom home in an architecturally significant Chicago suburb with exemplary public schools. I’m a freelance journalist with a girlfriend and a rent-controlled apartment. What my dad was able to achieve seems impossibly out of reach for me.

San Francisco is, in this way, a fitting deathbed for the American Dream. Overpaid tech oligarchs are squeezing the city’s middle class from one extreme; mentally deranged, drug-addled vagrants are doing so from the other. The Grateful Dead were able to hone their craft and launch their careers because San Francisco was still affordable in the ’60s. The Dead rented their home for just a few hundred dollars a month. Now, comparable houses in the neighborhood rent for as much as $15,000. The idea of a city that is both affordable enough to cultivate a thriving arts scene and safe enough to raise a family no longer exists. Our choice is an expensive slum or a prohibitively expensive cloister for the ultra-wealthy.

Dotting the crowd at the Golden Gate Park shows are Deadhead parents with toddler children sitting on their shoulders, wearing sound-cancelling headphones to spare their fragile eardrums. I was one of those children once. My parents, not wanting to spend money on babysitters, would take my sisters and me to Dead shows when we were just babies. I’m one of the few millennials who can honestly say I saw Jerry Garcia perform. Perhaps Dead fandom will be passed down to those shoulder-borne toddlers, just like it was to me.

Perhaps the next wave of Dead fans can redeem the band’s founding ethos. The current generation sure hasn’t. The most desired career path among members of Gen Z is social media influencer, which is essentially being a living, breathing vehicle for brand advertising. Selling out is the first and last stop on the highway. There is no great cross-country adventure to be had, no roads to get lost on. All the streets have been mapped on GPS. Anything resembling a counterculture is meticulously catalogued on social media. There is no mystery, no romance, nothing left to discover.

Basketball legend and avowed Deadhead Bill Walton used to say that with the Grateful Dead, “it’s all one song,” referring to the recursive nature of the Dead’s music. Much like the Grateful Dead’s music, the American Dream is imperfect. It’s an active, improvisational experiment, constantly shifting and being redefined. Sometimes the music is discordant and jarring; other times it’s transcendent. Dead? Maybe. As long as the music keeps playing, there’s always another chance it will all come back to create something beautiful.

John McDermott is a writer in Los Angeles. He has contributed to Esquire, GQ, and Rolling Stone. This is his first, and hopefully not last, time writing for Frontier.

John McDermott