© 2026 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

From farm fields to Music Row, Mary Kutter's turning small-town grit into protest anthems Nashville can't ignore.

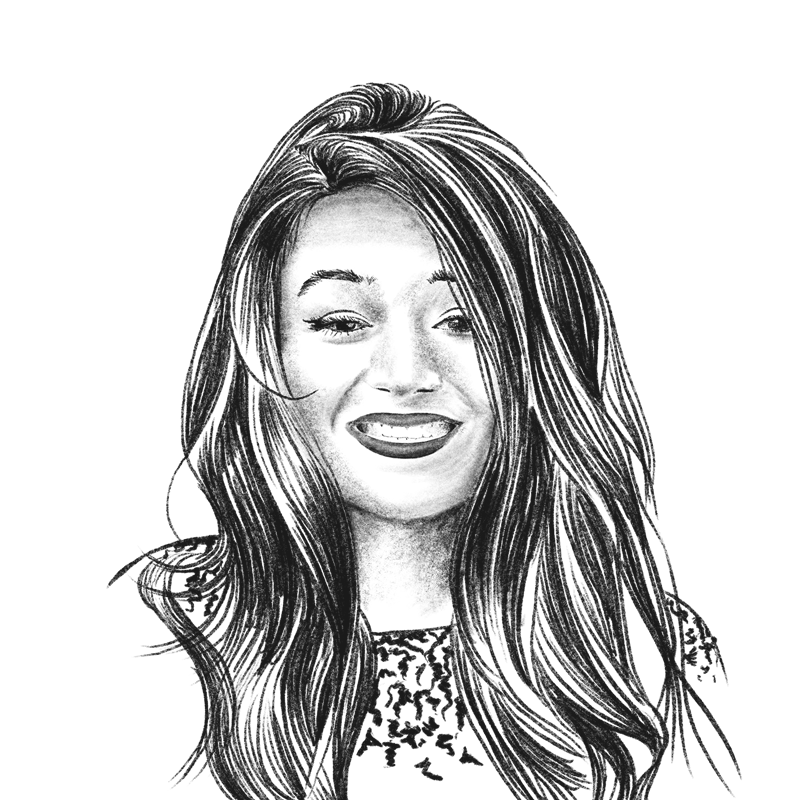

Mary Kutter catches you with her stare. Scroll through her Instagram reels and you’ll see it: a pair of sharp eyes, locked on the camera like she’s daring you to look away. It’s the kind of look that makes you stop mid-scroll. In Nashville, where talent is cheap and attention is currency, Kutter’s stare is its own form of music: piercing, defiant, with a visual hook to match the lyrical ones she writes.

But off camera, she’s something else entirely—warm, kind. “My parents raised me to treat the CEO and the janitor the same,” she insists. And those who’ve shared a writing room with her swear it’s no empty phrase.

The Kentucky native is one of Nashville’s hardest-working young songwriters, with more than 200 million streams on songs she’s co-written for breakout artists like Nate Smith and Bailey Zimmerman. And in an industry built on connections, she’s managed to hold fast to the values of Springfield, Kentucky, with a population under 3,000. When I spoke with her, I was struck by her joy, her gratitude, and her groundedness—far beyond what you’d expect from some-one climbing as fast as she is.

Country Roots

Springfield sits in Washington County, in central Kentucky. Kutter often says she’s from Bardstown, the next town over, because, with its 13,000 people, it feels “close to civilization.” But Springfield, her real hometown, is smaller than some high schools. It’s a place where Friday nights mean football, Sunday mornings mean church, and most families can trace their lineage without leaving the county line.

Kutter’s childhood was full of faith, discipline, and music. She was steeped in 4-H, serving as county president and traveling to national conferences. And on Saturday mornings, her father would drive her to Walmart with AC/DC, Steppenwolf, and Alice Cooper blasting from the car speakers. “That’s where I really fell in love with anything that was rocking,” she says. “Of course, you hear me talk and you can tell I’m a hick from the sticks—so country music flows out naturally. But what I do now is kind of a fusion of those two things.”

Both her parents were musical: her mother a pianist and singer, her father a bassist who once toured Europe with Donovan. They grew up poor, clawing their way out of poverty. “They taught me to work hard, to treat everyone equally, and to give it all you’ve got,” Kutter says. Dinner table conversations centered on passion for work. “I grew up seeing people who loved what they did,” she remembers. “It made me want that too—not necessarily the same career, but that same passion.”

The Squiggly Line to Nashville

Kutter didn’t grow up dreaming of Nashville. “It might as well have been Australia,” she laughs. She started singing in the church choir, at county fairs, and at festivals. One of those gigs introduced her to a Bardstown radio executive who asked her to host a weekly TV variety show. Every Saturday, she interviewed artists and songwriters on radio tours, opening and closing the show with her own songs. That’s where she met Kim Williams, the legendary songwriter behind hits for Garth Brooks, Randy Travis, Reba McEntire, and other country icon hitmakers. Williams handed her a golden ticket: nine Nashville phone numbers. “Call them,” he said, “Say Kim sent you.”

She did. Soon she was driving to Nashville three or four times a week. By the time she finally moved full-time, she had already built a network.

Once in town, she hosted writers’ rounds in Midtown, booking nearly 500 different performers in less than a year. Watching hundreds of songs night after night gave her a crash course in what separated the good from the great. “It was like a PhD in songwriting,” she says.

Mary recounted her intimidating first impressions of Nashville:

Everyone’s beautiful. Everyone’s got great songs. Most people know somebody. I moved to town in this old Buick. I didn’t have two nickels to rub together. I’m really gonna have to work hard and work smart.

Then the world shut down. When COVID turned off Nashville’s neon lights, Mary headed back home to Kentucky—her career seemingly on pause, her momentum stalled. But perhaps it was that final dose of Kentucky that took her career to the next level, and it started with advice from her father that changed her life: In a world that’s losing control, focus on what you can control.

So she did. She began writing sessions on Zoom seven days a week, sometimes three sessions a day. She woke up at 5 a.m., read, journaled, and ran five miles every day before her first session. “It was during that time that I really started writing songs that started moving the dial for me.”

The grind paid off. With Nate Smith, she co-wrote “Sleeve” and “Wreckage,” winning her a gold record and Billboard Top 20 hit. With Bailey Zimmerman, she co-wrote “Never Leave,” a SiriusXM #1 that put Zimmerman on the map. Her work also includes Alexandra Kay’s “That’s What Love Is,” which charted on iTunes at #1, and Haven Madison’s “How You Like Me Now.”

Songs That Tell the Hard Truths

If her co-written songs proved her chops, her own songs proved her courage. She isn’t afraid to take on subjects Nashville usually avoids: bootleggers, opioids, outlaw farmers, and poisoned rivers.

“Devil’s Money,” released independently in late 2023, tells the story of her great-grandfather, a bootlegger during Prohibition who donated much of his profits to build a church in Bardstown. The story is messy, morally gray, quintessentially Kentucky. Illegal liquor paid for stained-glass windows. Sin built a sanctuary.

The song went viral on TikTok, pulling in millions of views and shooting to #7 on the iTunes country chart—an unheard-of feat for an unsigned artist without a PR machine. Listeners flooded the comments with their own family histories: grandfathers who ran shine, uncles who tangled with the feds. Kutter had tapped into a shared Kentucky memory: survival in hard times, even if the means weren’t clean.

In her viral hit, “Devil Wore a Lab Coat,” Kutter takes aim at Big Pharma’s opioid invasion of Appalachia:

“One man’s grave is another man’s pay-check / RX meds at our expense / Forget the coal mines, they hit a goldmine / Hooked us on six feet of side effects.”

It’s just as much a protest ballad as it is a country hit, weaving a clear-eyed indictment of how pharmaceutical companies targeted small Kentucky towns, handing out OxyContin like candy while doctors cashed in on kickbacks. In Kutter’s telling, the drug reps weren’t slick businessmen; they were predators in white coats. “Appalachian map dots were the perfect bullseye,” she sings. And in communities where coal had already collapsed, pills became the new company store.

Kutter had tapped into a shared Kentucky memory: survival in hard times, even if the means weren't clean.

If “Devil Wore A Lab Coat” tackles Kentucky’s opioid wounds, “Smell the Smoke” recalls another chapter: farmers swapping corn for cannabis when crops alone couldn’t meet the bottom line.

“Mary Jane’s hiding in the back of that field / Sam sent his boys but our lips are sealed / Mighta broke the law but they’ll never break us down.”

It’s not just a song about weed—it’s about survival and the kind of communal silence that defines small towns when the feds come sniffing around. Washington doesn’t scare Springfield. “Sam can print his own, don’t gotta grow his own money,” Kutter spits, painting a portrait of ordinary people who have to get by in a rigged system.

Her most recent protest is the still-unreleased but viral “Dirty Money, Dirty Water,” a song about a Henderson, Kentucky, chemical plant that dumped mercury into the Green River. Residents got cancer; corporations got rich.

“Tombstones don’t lie,” Kutter insists, a line that echoes the refrain of “Devil Wore A Lab Coat.” It’s a song about betrayal—of a river poisoned, of a community left behind, of money trumping human life. It’s the kind of subject most mainstream country music won’t touch, but for Kutter, it’s part of the job.

To most of the country, these stories are headlines that quickly fade into the ever-churning news cycle—disembodied words describing forgotten people. But not for Mary Kutter. These are her people, and she knows they are one of many communities continually bullied by the “big guy,” whether that’s Uncle Sam, corporate greed, or Big Pharma. Her songs tell their stories, not as victims, but as people of grit, who always get up, no matter how much they’re knocked down.

“If I can be a voice for the voiceless, that’s a very powerful thing.”

Part of what gives Kutter credibility is that she doesn’t just sing about Kentucky—she embodies it. Her grit is inherited: parents who escaped poverty, great-grandparents who made do with bootlegging, a community that built beauty out of hardship. “Where I’m from, there’s so much beauty,” she says, “but also a lot of poverty and a lot of vices—bourbon, betting, bootlegging. For better or worse, people did what they had to do to get by. That’s always inspired me.”

It’s why her stare on Instagram feels less like performance and more like witness. She’s not posturing. She’s testifying.

A Stare and a Smile

The duality of Mary Kutter is her most magnetic quality. On TikTok and Instagram, she looks like a gunslinger: unblinking, sharp-jawed, eyes locked on the viewer. She sings of family sins, poisoned rivers, and Kentucky grit with the fire of someone who’s lived it. But in person, she’s all warmth. An artist who never takes anything for granted, but also never sells herself short of being able to achieve her dreams with honest elbow grease, sweat, and raw, unvarnished talent.

“Her music is aggressive, and it’s as true as you get,” Tully Kennedy, the bassist for country legend Jason Aldean, raved:

She’s backwoods... she’s so Kentucky, she’s so authentic... and she’s the first female I’ve seen in a really long time envisioning opening up for us on the road... that people give a shit about.

So far, Kutter’s climb has been completely on her own—no label, a self-built network, grit, and elbow grease. But Kennedy predicts it’s only a matter of time before Kutter is going to make it big—really big:

When labels say, “We need something different,” and you bring in something different, they get scared. And she’s going to land in the right spot, and she’s going to hit, because no one is doing it.

Mary Kutter isn’t chasing stardom so much as she’s embodying it—song by song, session by session, mile by mile on her morning runs. Her story isn’t the stuff of Nashville myth, where some 18-year-old moves to town and finds a hit within months. It’s slower, tougher, more real. It’s about a girl from a county fair town who built a career the way her great-grandfather built a church: with sweat, with grit, with whatever resources she had.

Kentucky shaped her voice. Nashville amplified it. And with her piercing stare and rugged testimony, she’s hooking the rest of the country along for the ride, too.

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

Katarina Pfister is the deputy opinion and analysis editor for Blaze News and an associate editor for Frontier magazine.

Katarina Pfister

Katarina Pfister is the deputy opinion and analysis editor for Blaze News and an associate editor for Frontier magazine.

more stories

© 2026 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.