James Poulos

Elena Velez, New York’s black sheep girlboss, sews chaos into couture.

I was in Times Square, New York City’s tacky-and-proud ground zero of commercialism, to see Elena Velez—the only famous fashion designer me or anyone in my circles knows personally, so, probably, the most famous fashion designer nobody outside New York or L.A. has ever heard of. But at this moment, with America’s running war over all things race-class-and-gender flaring up in the city with fresh heat, Velez feels poised for a break into conspicuous notoriety.

On the way to her studio—tucked above the traffic along an archetypal cones’n’manholes midtown sidestreet, the coffee-powered interns you visualize weaving through its racks of clothes as you ride up the freight elevator materialize at the industrially Lynchean door to slip you inside—I steered clear of Thomas J. Price’s Instagram-ready statue of an ample-figured black woman in a pose of laid-back defiance. It had just gone up between West 46th and 47th Streets, and the mania surrounding the installation intensified in the glare of the intersection’s video billboards. Coincidentally, of course, they blasted “body positive” dating-app propaganda encouraging the obese, the ugly, and the otherwise “conventionally unattractive” to proudly present themselves as advertised.

Inside Velez’s studio, she settled swiftly into a tour-driven conversation that spilled over, after an hour, across the street to her favorite local, where we sipped traditional New York tap and well drinks on a breezy rooftop and solved the world’s problems over several hours more. It’s a space that reminded me with a pang—during the 2010s I spent a lot of time in New York, where for a moment I had more friends and colleagues than in my hometown—of the “old New York” I loved in that era: an arch urban Arcadia, where neolib conventionalism made political time stand still in a manner affording the all-in arts person a long shining moment of focus, fun, fruitfulness, and, of course, fashionableness.

It was an age of access—not the freemium online kind, cheap up front, taxing at the exit, but subtly, sumptuously embodied: cable TV hits en route to unadvertised boho apartment parties, artist passes to Gov Ball, hanging in the headliners’ trailer after a warm, complete downpour… almost everyone ages out of these things, but in New York, continuity of cultural memory and experience has always been generationally guaranteed. Is it still?

There are still celebrities, after all—people famous for something besides being famous – and many of them still prop up New York’s mystique when it sags in other areas. And a lengthening laundry list of them are wearing Elena Velez: Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Grimes, Doja Cat, Teyana Taylor… you might not know them all, but their many millions of fans and followers do. Velez isn’t just a name on the catwalks, at the Fashion Weeks, in the Times. She’s in as many Instagram grids and reels as there are people in major cities.

And here’s the funny thing about Velez, and about fame in 2025. The same edge she’s earned in the highly competitive industry from her insistence on countersignaling the conventional ideological programming has led to… well, problems. Vague reprisals that at once heighten her unique prestige and cast a cloud over her clout.

When I ask if her A-list clients are conscious of their involvement by proxy in that problematic complex, she admits she’s not entirely sure.” I don’t know who absorbs what source of media. In the beginning I was kind of a fashion darling and was in all of the editorials and all of the print pieces, but it’s not hard to be found by stylists and people who facilitate those sorts of connections. It is their job, actually,” she laughs. “Or else they get fired! I got bored with that. It was too easy. And I wanted success on my terms, on my existential terms—and now I’m in time out.”

As in, you were bad and you’re being punished? “Yeah. I’m a little bit of a black sheep right now in the industry. I think I’m kind of in time out because I’ve done a couple of projects that have just not mapped cleanly enough onto the industry’s hyper liberal matrix.”

That would include the infamous (for New York) “longhouse” fashion show, culminating in a very fashion mud wrestling moment. “When at last the models enter, they walk with the slow, lurching determination of zombies. Their hair is matted with white paint that also stains their faces like the celebrants of some Paleolithic ritual.” This is Justin Lee’s eyewitness account at First Things. “As they walk their circuit they are expressionless, with thousand-yard stares of trauma survivors—or rite-drunk bacchantes. They’re dressed in outfits that, like the strange, pulsing music, seem at once post-apocalyptic and a reassertion of older styles. The designs, made from materials Velez describes as ‘debris,’ suggest a blasted earth whose inhabitants still feel compelled to adorn themselves in what beauty they can wrest from the decay.”

“At the show’s end, the models return in single file to circumnavigate the arena so the audience can have one last look at the designs. Mid-circuit, however, the music abruptly stops. Shrieking, the models fall upon one another in a frenzy of hair-pulling, shoving, wrestling, even animalistic kissing. The sand is revealed to have been a thin veneer covering a mud pit. The models grapple in the filth, which slathers onto their garments, perhaps ruining them. Slowly, they filter off the stage and into the darkness.”

Well, I ask, some of this is intentional, right? Velez speaks matter-of-factly. “I’ve always been extremely aware of what the consequences of making a statement would be. And so I’m not a victim whatsoever of the negative media that I have incurred. But it’s been essential to almost do high altitude training for the artists that I want to be and see more of out in the world. You have to be kind of forged in fire and you need to be, you need to learn how to sit with the discomfort of being misunderstood and disliked. To the extent that there is a culture that can be spoken of.”

She describes it as a paradoxical culture of everything permitted, nothing allowed. “If you stray from the vector of permitted transgression, then, you know, you’re on notice. I have a very paradoxical and nuanced commentary on womanhood and the female experience post MeToo, post woke culture. It’s a brand of womanhood that I just don’t see on the creative coasts. It’s about taking responsibility for your desires, both good and bad, and making no excuse for your proximity to wickedness. And being somebody who activates all of the potentially nefarious, sexy parts of being a woman into an ultimately virtuous pursuit.”

She’s on a roll, articulating something I’ve heard from more than a few women straining to establish stable space between homesteading and OnlyFans. “There’s something that I like about a woman who vice-signals. Somebody who overcomes all sorts of internal darkness, struggle, to do something ultimately good and meaningful. It’s definitely implicating myself in the critique—a girl boss and a relentless capitalist and a mover and a shaker in New York City, but also somebody who has a very incongruous, very traditional, and esoteric mission.”

Under online pressure to seek refuge in the instantly verifiable and performative identity, whether cartoonishly old-fashioned or grotesquely progressive, America’s girls and women struggle to create and tend living gardens somewhere in the country’s great midsection of the soul.

This city seems increasingly unwilling to allow, to “hold space for,” to countenance and understand. Velez alluded to it in our conversation, and she’s said it elsewhere: New York sucks right now. Maybe not in those exact words—and it’s a theme I hear in just about every “leading” city I visit—but I ask her: if the suck went away, how would you know?

“I think there would be a more charitable willingness to engage with complicated ideas. There would be more spiritual buoyancy.” She sighs. “There would be more humor. I think there would be a levity and a silencing of the voice inside of our own heads that makes us second guess when we call somebody him or her or when we interact with somebody who is unlike us culturally. It’s like a really unfun time to have a public profile.”

Another gift of the internet—or at least of what it welcomes from people. When I suggest the only people who seem capable of weighing in meaningfully on this social psychosis ruining fame’s ostensible benefits are the craziest people, she laughs. “Because they have committed egoic suicide. Nobody can humiliate me, because I humiliate myself every fucking day. Every day I wake up in the morning and I’m ashamed of something that I’ve done. And after living with that for a couple of years, you’re like, you know what? Fuck it.”

What’s she so ashamed of? “Oh, God. All sorts of things. Like I’m embarrassed about how little control I have over curating my public image. You know, like very tedious, mundane material things. I’m embarrassed about the way that I’m inadequate in taking care of the people that I love or collaborate with… my face and my style and, like, living in New York and loving fashion. All these different really silly things that you have to just destroy before you’re going to transcend it.”

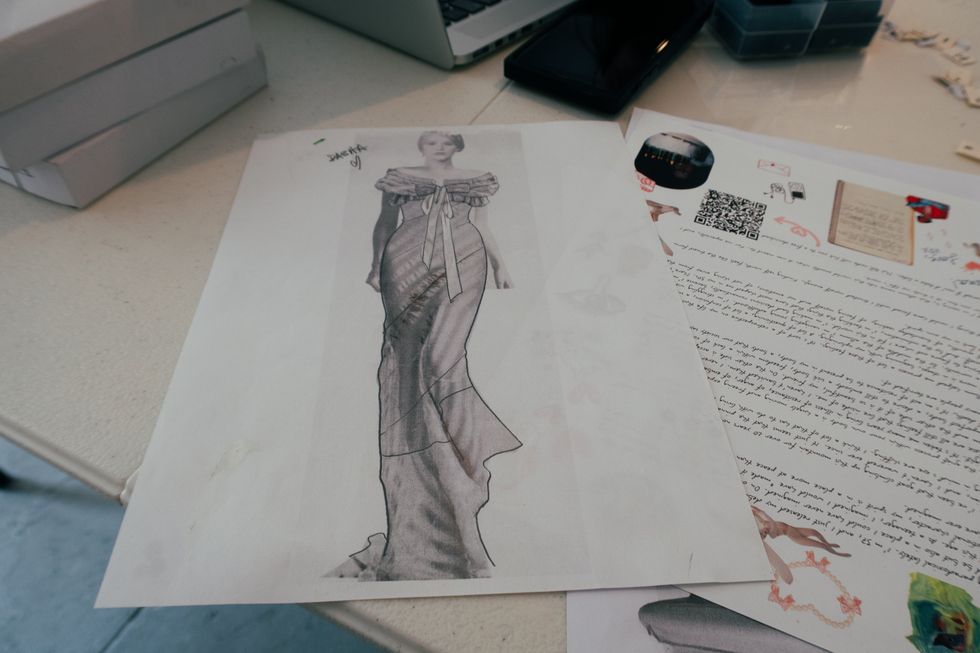

“La Pucelle,” Velez’s Spring-Summer 2025 collection and her largest yet, recast iconic historical figures as current-day “renegade pageant queens and patriots.” Courtesy of Elena Velez

This, here, is the key to understanding Elena Velez—the person, the label, the brand. Is it really that silly, I press her, to feel like you can’t love those who love you because you have to make your art project?

“I know what that is.” She nods. “A lot of people do. It’s like I wish I had more time and more altitude and more breathing room to look around me and say, ‘Hey, thank you. You did a great job doing that. I really appreciate that.’ Little things like that, that I just don’t feel like I have enough gas in my engine to accomplish. The come up”—that is, becoming recognized as an actual, legitimate success—“is really embarrassing and cringe, and the reason you keep doing it is it’s like, ‘okay, I’m going to circle back and say that I’m so sorry to that person in like two years when I have a thousand dollars to just give them, you know?’”

What explains this—is it guilt? Is it conscience? No, there’s something more—turns out to reside in a past that no amount of glamor or social credit can erase. A Midwestern girl with a quintessentially quirky New World upbringing, fashion quickly became her only lodestar—one which lifted her almost at once to the heights of the industry, via the elite Parsons School of Design, and the deep epicenter of fashion and the Old World that is Paris, France.

It’s a neoclassically American kind of story, one that Hemingway and Fitzgerald would have immediately recognized—and, no doubt, immortalized. Drawn by “this divine compulsion towards this thing that I could never really articulate, that I didn’t have cultural references for, that I didn’t have the means to manifest”—insert Gatsby reference here—Velez carries from childhood “a life of trying to understand what that’s about. I haven’t gotten any closer to it.” She pauses. “I don’t get it. It’s strange. If I could choose to love any other thing, I would, a hundred percent, but being in rural Wisconsin, like, I had no proximity to any sort of lifestyle in fashion.”

How rural, exactly? “Corn. Just corn.” But, as any true Midwesterner knows, the vibe runs much deeper than that in this world unto itself. “Wisconsin’s really exciting because you can drive 30 minutes in any direction, and you’re in a totally different, like, geographical landscape, so you drive 30 minutes east and you’re on the edge of Lake Michigan, which is just a horizonless body of water.” Her mother a Great Lakes ship’s captain (yes, she spent a lot of time on the water), her father a wayfaring, “worldly” Puerto Rican, Velez has peregrination in her bones, and her heart. “When I was growing up, like, I had no idea where I was going, just that I had an obsession for this very strange craft.”

It didn’t come from online. “I was born in ‘94. We didn’t have internet until I was at least 12 or 13 in our house. Project Runway came around in like 2007, 2008, which was kind of the thing that gave me the language.”

Languages come fairly easy to Velez: she stacked them in preparation for a global life in fashion. “I went to language immersion programs through, like, middle school, elementary school, high school, and I was going to be a government translator while I was kind of trying to figure out a more ‘realistic’ path for my life after graduation.” She chuckles. “I know. So I applied to all these colleges, everyone said ‘no,’ except Parsons Paris, which was willing to offer me a free ride, basically, to study in France. So I kind of decided where I wanted the coin to land while it was tossed in the air. That was kind of the only moment where I left it up to fate, and the universe.” And so the speedrun began. Brazil for a year, Paris straight after. Two years, then New York.

Those two Parisian years were pivotal. And not by design. Millions in Hemingway’s generation learned their own way the nature of Velez’s coming-of-age confrontation with the Old World. “It was, like, 2013, 2014. There was a lot of terror. There were a lot of, you know, bombings at nightclubs, there were shootings, it was a very tense time. Paris was starting to struggle with its own self-image in terms of the new immigrant population coming in.”

Velez was mugged on the streets multiple times. Friends were assaulted in front of her. She was in the city during the Bataclan massacre. “It was kind of the first time where I ever really experienced geopolitical ‘tension’ in my own little cosmopolitan fashion bubble. And I’m a 9/11 baby—like, this is not new to me, but I had to reconcile with it as a young adult and add that to my impression of the world.”

If you can’t make space for your own artists and your own free thinkers within this sort of ideological umbrella, then they’re going to move.

Which brings us back around to New York. Like so many brilliant expats, Velez didn’t stick around long. She hit “the States” with a sort of vengeance—seizing and commanding the attention of the city’s precarious late ‘10s early ‘20s scene, where a fractured left fumbled its bid for iron-fisted control and a rising “dissident right” snagged scaremongering headlines far out of proportion to their influence and numbers. Velez boasts a unity of theoretical vision and practical skill undeniable enough to win the respect of the academicized arts world—and with the imprimatur of the Times and a growing roster of bona fide celebs, Velez quickly began to change the cultural terrain taken for granted by more comfortably ensconced elites.

Along the way, her insubordination, free-spiritedness, and just plain drive has cut increasingly—to the irritation and shock of the industry’s gatekeepers and critics—against the grain of the Obama/Biden-era’s strictly enforced civil religion.

“At this point,” says Velez, “all of my quote-unquote ‘right wing’ affiliates are disgruntled, disaffected leftists—who will always be spiritual leftists, but just want to, like, have a modicum of free speech.” Spiritual leftism, she adds, involving “a perception of being the only one who can define empathy. It’s like a very hyper-feminized sort of mindset.”

And while many New Yorkers banished from the policed left will, she believes, never make the transition into full-blown right-wingers, she prefers the company of nonconformists whatever the label on their identity badge.

“I think that the leftist project failed when it cut out its eccentrics and its bohemians,” she suggests. “Anyone who critiqued from the inside or posed questions was removed from the project. If you can’t make space for your own artists and your own free thinkers within this sort of ideological umbrella, then they’re going to move. And it’s like a lot of these people haven’t changed. The cultural political center has moved and adopted them. So yeah—a lot of people who value free speech and creative expression, undiluted creative expression, have inevitably at least moved to the center these last few years.”

She lingers on this subject for a while, and we talk about how it’s all about loyalty—if your loyalty is not immediately legible, you are suspect. And because it’s the internet, you are persistently reminded at all times that, no matter how much praise or hate you get, you are in fact not special. And if you think you are? Guess what: there’s a functionally infinite line of people who are, to a very close approximation, your clones, who the gatekeepers, police, and critics can kill off (“cancel”) so the next, more compliant version of you will pop up and slide forward in the great online vending machine. That version’s loyalty will be instantly reliable and verifiable: she’ll know, having watched your original version get executed, that she’s next in line for elimination if she doesn’t immediately conform.

“That’s why it’s essential,” Velez intones, “that you have a singular talent that is not replicable. And that’s… that feels like a room for me. That feels like a space where I can be sustainable, if that makes sense. Like I know that whoever’s team I pitch for, whoever claims me, whoever hates me, whoever loves me, like it’s not going to do anything to my talent and my ability to make something beautiful and meaningful.”

The yawning expanse is not a plain peppered with roving killers but a depopulated realm of being and consciousness where the normie “art hoe” is as rare and persecuted as the tricky and troubled “trad”.

The key to the New York City mythos is that it’s the heart of America, the center of it all. For most countries, the focal point and center of gravity is the nation’s capital or the geographical midpoint. Often, these are the same spot on the map. But America isn’t like most countries. Just as New York City isn’t like most cities, America meets, exceeds, and finally transcends the template of what has come before.

The United States defines the New World through its new way of being a country: not by spawning a new Old World-style regime from scratch, nor by blowing away its old stock in a perpetual blast of newcomers, but by somehow incorporating and reconciling both old and new in its people, its mores, its spaces, and times.

Between the frontiers of the body and the core, the heart, there is the valve, the busy two-way portal through which everything must pass to recirculate. New Yorkers, even at their most logocentric, have always been wise enough not to call their boroughs the heartland of America. They understand even better than the rest of us that their true function is as the great valve at the border between the Old World and the New.

It’s a portal that transcends even the politics of ideology and immigration, now roaring back to the city’s fore in the wake of intersectional coolguy Zohran Mamdani’s victory over the high-modern hyphenate-American Andrew Cuomo.

Reflecting amid the fallout on the city’s current-year class situation, Persian Rumi scholar Muhammad Ali Mojaradi posted a pithy assessment to X of the WASP’s quietly enduring power—or, at least, the power of Northern European white girls, seen as instrumental to Mamdani’s win. “High status in NYC is to be a local WASP, attend a Northeast Ivy or Ivy-adjacent school, live in an ornate pre-war building with inherited rent control, and have a job in a creative or non-profit industry,” he began, teeing up a comparison between imagined representative types.

“Elizabeth Wilmington was raised on the UWS, went to Barnard, is now a Librarian at Columbia, lives in the apartment where she was raised, and her parents retired to Italy. Midwestern strivers, making $250,000 in finance or law while living in a high-rise Long Island City IKEA apartment, have none of this swagger. Michael Jerkowski from Columbus, Ohio, might make triple her salary, but his Ohio State degree and apartment in Williamsburg scream ‘low status’ to Elizabeth; he can’t get her to text back.”

What’s at work here is the malfunctioning of the New York City valve: eligible heritage white women turning against not just “normie white guys” but against ambitious New Worlders altogether, in favor of Old World elites on the make—including the city’s growing share of charismatic postcolonial Marxist international developing-world-raised non-Christian activists such as Mamdani.

To West Coasters (such as myself), who never felt at home on the Atlantic seaboard or amidst the inland seas of corn, the role played by the collapse of Hollywood’s glamor-making institutions plays a conspicuous role in the seemingly faraway breakdown of New York’s circulatory function between Old World and New. “People come to L.A. to make it in the arts,” I responded, “without it having to be in some way an economic or psychological condition of their having their particular family.” Hollywood’s breakdown “tilted arts culture dramatically back toward the cursed ‘Old World’ of Northern Europe. Dynastic sadomasochism, obscure fetishes, transatlantic intrigues, arms dealers, blood money. Years spent without seeing the sun. The cold erotics of death.” If New York fails in its crucial valve function, can Los Angeles still rise to the occasion? “Only SoCal can return us now to the New World… to the Med… ” Then again, we can no more imagine an America without New York than we can without California…

And that means paying very close attention to what New York’s most original and most dedicated creative women have to say to us now. Elena Velez—and much of the strikingly large class of women reaching from Taylor and Beyoncé to their forever-unknown fans and followers—find themselves at a frontierland every bit as wild and menacing as that faced by America’s pioneer women a century or two ago. Only this time, it is a psychological and spiritual one more than a physical one. The yawning expanse is not a plain peppered with roving killers but a depopulated realm of being and consciousness where the normie “art hoe” is as rare and persecuted as the tricky and troubled “trad”. Under online pressure to seek refuge in the instantly verifiable and performative identity, whether cartoonishly old-fashioned or grotesquely progressive, America’s girls and women struggle to create and tend living gardens somewhere in the country’s great midsection of the soul.

“That’s the thing,” Velez says, pinning down the heart of the matter. “If you can’t make yourself orgasm in your own life, like, nobody else can. I am a self-described chaos agent. And I love nuance and greyscale and multiple truths. And I feel just so inspired and energized by this moment of no singular authority having the answer. I don’t have any answers. I’m just living my life in a way that feels most authentic to me and hoping that other people can kind of articulate it for me. And it’s working. But I haven’t made it. I can’t think about other people.”

Making it in 2025 meaning—what exactly? “Having enough money to do it again. Whatever it is. To do another fashion collection, to do another novel, to stay in your apartment another month. To continue. At your current level.”

And maybe a cut above that?

“Not even. That’s luxury. Making it is taking another breath.”

James Poulos is the Founder and Editorial Director of Frontier and Return at Blaze Media, and is the host of Zero Hour on BlazeTV. He is the author of Human Forever, The Art of Being Free, and the forthcoming Golden Age Problems.

James Poulos

BlazeTV Host