Sian Roper

Detroit’s felonious, philandering Mayor never had a chance.

I was 19 years old on New Year’s Day, 2002, when a 31-year-old Kwame Kilpatrick was sworn in as the youngest mayor in Detroit’s history. Detroit is both the city listed on my birth certificate and a national punchline because of stories like his. But such stories are also a big part of why I love my city.

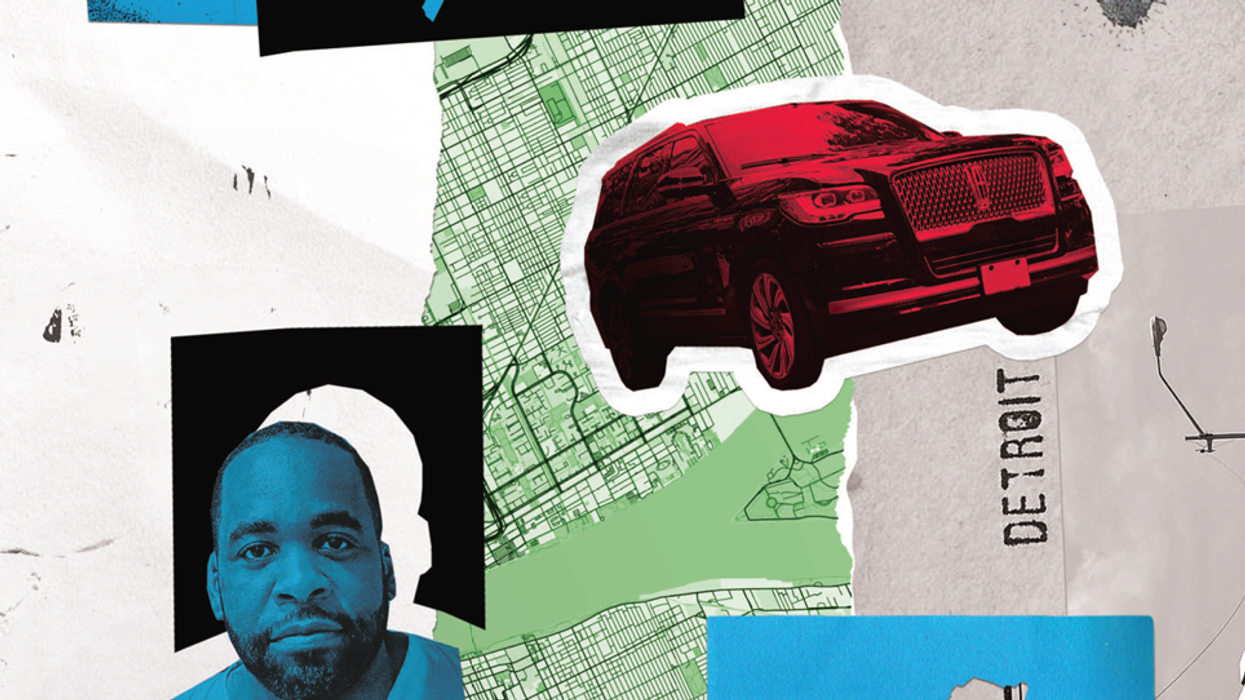

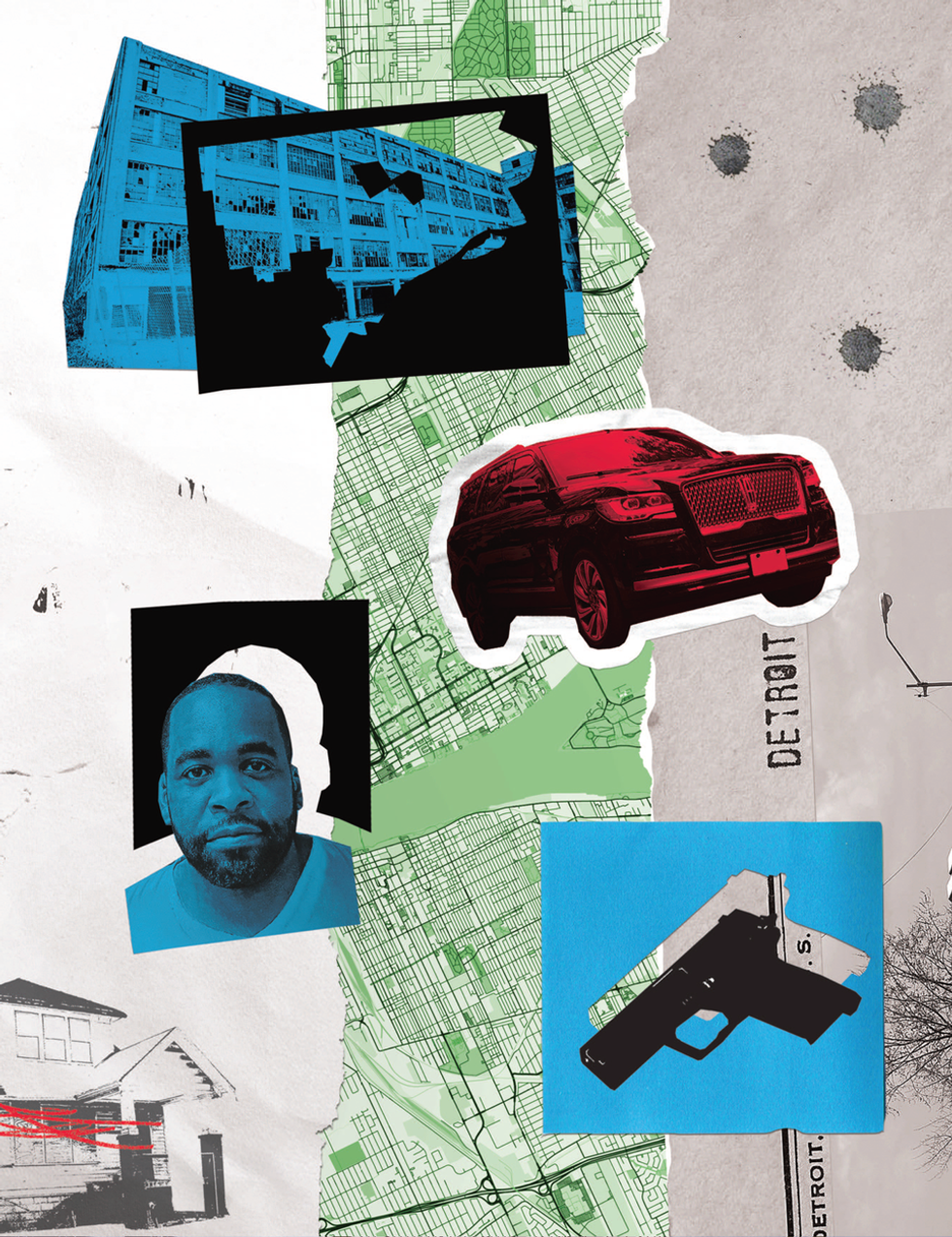

Rocking pinstriped suits and a two-karat diamond in his ear, Kwame was known as “the Hip-Hop mayor,” even before his stint in federal prison on 24 felony counts gave that nickname street cred. He even leased a red Lincoln Navigator in his wife Carlita Kilpatrick’s name with taxpayers’ money—five dollars under the threshold for a city council purchase review, to be precise. You must really love your wife to rob a city in plain sight to get her a luxury SUV. Either that, or your ex-girlfriend Christine Beatty is now your chief of staff, and bribes aren’t the only thing you’re getting on the side.

Everyone was on the payroll, and he made sure the checks cleared. That control gives a young man power. Is he at fault for his actions and responsible for his choices? Certainly, but we’re all sinners.

In spite of all this, Kwame was a breath of fresh air in politics, and I liked him. He looked more like Suge Knight walking into a Death Row Records release party than the elected head of a municipality. The fact that he came off more like a gangster added to why I thought he could run Detroit properly. At the very least, Local 4 News would be funny.

During Kwame’s first year in office, my brother and I were painting a beautiful old house near the mayor’s residence—the Manoogian Mansion—a stunning Spanish Colonial Revival estate that sits on Dwight Street overlooking the Detroit River. Resembling a slightly less tacky El Fureidis (the mansion used for Tony Montana’s house in the movie Scarface), it only added to the impression that Kwame was more of a criminal than a councilman.

Every previous mayor of Detroit had taken up residence at the Manoogian, but I didn’t know that at the time. I also had no idea that “wild parties” were against the rules. I partied with every dollar I made back then, so large get-togethers didn’t seem out of the ordinary to me. I mean, why even be rich and powerful if you can’t enjoy it?

Virtually every time my brother and I would show up to paint, cars belonging to people pulling an all-nighter at the mayor’s mansion would line up and down the entire street. No one was in the front yard except for what appeared to be police and security. However, in the back, facing the water, the luxurious stone patio and bedroom balconies were crowded with people dressed to the nines—mind you, this was usually around 6 a.m. Their night was winding down while our workday was just beginning.

It’s rumored that at one of these parties, Kwame met 26-year-old Tamara Greene, a stripper better known by her stage name, Strawberry. Tamara allegedly carried on an affair with Kwame, who to this day denies those allegations.

One night—though never confirmed—it’s said that Carlita Kilpatrick returned home unexpectedly and caught Greene giving her husband a lap dance. Furious, she beat the crap out of Kwame’s mistress outside the Manoogian, leaving puréed Strawberry all over the front lawn. Tamara reportedly feared for her life in the aftermath—a fear that would be realized months later when she was killed in a drive-by shooting. An autopsy traced the bullets that killed her to a .40-caliber pistol—the same caliber of standard-issue Detroit Police Department Glocks—leading many to speculate that this was a Kwame-ordered hit carried out by corrupt cops.

However, the department and others argued that she was simply caught in the crossfire of a lethal drug feud, pointing to her boyfriend Eric Mitchell’s rival, Darrett King, as the likely assailant (Mitchell was struck five times yet survived). An investigation by then-Michigan Attorney General Mike Cox would find no evidence of a party (ha!) or a murder conspiracy, but the ground was trembling beneath Kwame’s Gucci loafers.

The Manoogian Mansion controversy was just the first block to be pulled from the Jenga tower that was Kwame’s political career. A 2007 whistleblower lawsuit unearthed text messages proving he’d lied under oath about an affair with Christine Beatty and had fired a cop who attempted to probe his administration, costing the city $8.4 million to settle. That triggered 2008 state charges for perjury and obstruction, forcing his resignation, followed by a 2010 federal indictment for running a “Kilpatrick Enterprise”—extorting contractors, rigging $127 million in contracts, and pocketing $1.7 million in bribes.

Convicted on 24 felony counts, including racketeering, bribery, and fraud (pretty much everything except murder), he drew a 28-year sentence in 2013. After serving seven years, President Trump commuted his sentence at the end of his own embattled first term, possibly to secure the black vote in Wayne County, Michigan, for 2024—or just because he thought it was hilarious. This move shocked even Democrats because Kwame, not surprisingly, was a Democrat.

More than anyone, Kwame Kilpatrick personified Detroit’s cautionary tale—not as the city’s affliction but as a symptom of its deeper, more terminal illness. To me, the city’s unraveling began in July 1967, when one of America’s deadliest race riots tore through its streets over five days. In its wake, white residents and businesses fled to the suburbs, abandoning their homes and solidifying a racial divide that endures to this day. Once celebrated as “the Paris of the Midwest” with nearly 1.85 million people in 1950, Detroit now clings to just over 639,000—and I’d bet the real number is even lower.

So why do I write in defense of Kwame? Because I don’t think he ever had a chance. The road to hell is paved with good intentions, but once you get enough carrots dangled in front of you, it’s only human nature to take a bite. Coleman A. Young served as mayor of Detroit for an even 20 years, and while there is little doubt of his corruption (though never proved in a court of law), black voters loved him. After that was Dennis Archer—mayor from 1994 to 2001—perhaps best remembered for his moral flip-flop on casino gambling. Then along came Kwame, who had some big shoes to fill as a young man in a city dead set in its corrupt ways.

When a Sicilian becomes a “made man” in La Cosa Nostra, he doesn’t start making changes. He works to fit in, and an even bigger fish calls the shots. Even if you’re the boss, you have a boss. I believe Kwame realized he had a pay-or-pray arrangement involving his life. Everyone was on the payroll, and he made sure the checks cleared. That control gives a young man power. Is he at fault for his actions and responsible for his choices? Certainly, but we’re all sinners. His flagrant corruption was the result of a young ego that had been blown out of proportion. People who are competitive get upgraded to assistant manager, and things go sideways. Just imagine what would happen if they were given keys to an unregulated kingdom.

Detroit could be considered a microcosm of the United States and a harbinger of things to come. Against a backdrop of abandoned car factories and boarded-up homes, Kwame mortgaged the American Dream that Detroit had once embodied for the kingpin’s Political Dream, where those in power eat first while everyone else starves. America has become a big business, where politicians buy stock using our lives as collateral.

Gil Hill served as the Chief of Homicide Investigation within the Detroit Police Department from 1982 to 1989. He was also rumored to be corrupt, but much better known for playing Inspector Douglas Todd, Eddie Murphy’s captain in three Beverly Hills Cop movies. Why get an actor when the real guy from Detroit is even more foul-mouthed and funny? Deep down, Detroit and its neighbors like that the city is filled with problems. White suburbanites have a convenient reason to never visit—while black residents get to tell whites that they don’t belong. The Motor City keeps the tank of racial tension in America full and proves that no matter the circumstances, we can always find a reason to be divided. Kwame was just a younger, hipper version of a centuries-old system—and the excuse everyone needed to stay set in their ways.

Dave Landau is a stand up comedian and hosts the show Normal World on Blaze Media. His first book Party of One: A Fuzzy Memoir, is now available and a bestseller on Amazon.

Dave Landau