Mike Mercury

A Report from an Independent Sunni Syria after the Revolution

Damascus was suspended in its post-revolutionary orgasm when I arrived with one friend and no plans. On the buildings were tagged timestamps, which marked the very moment, 6:08 AM, when rebels announced Bashar Al-Assad’s departure from Syria.

Just outside the Umayyad Mosque, inside of which John the Baptist’s head is allegedly enshrined, there were celebrations. Several journalists, as witnesses to dancing revolutionaries, stood awkwardly along the fringes of the public square in the same way introverts watch more fun people at parties.

I bought a SIM card so I could call home. The cell service provider required scans of my passport, several headshots, and my fingerprints, which together amounted to more surveillance than what was required at immigration. The airport in Damascus had been closed since the uprising and so, without other options, we flew into Lebanon and then crossed the border by car.

While we became “friends” with jihadists, exchanging stories and sleeping on their cold floors, journalists only left their hotels, like mosquitoes, to siphon off anecdotes until full, and then retreat to their swamp to contrive compelling stories.

Our driver turned out to be both an escort and a smuggler. After leaving the airport in Beirut, he filled his taxi with half a dozen garbage bags containing nothing else but eyelash extensions. At the border, the officer at passport control was more interested in this, the cosmetic merchandise, than in us, some of his first international visitors since the revolution. After some wads of cash were exchanged, the reason for his selective attention became apparent. I asked our driver whether such import duties were bribes or taxes, which, as it turned out, presented him with a false dichotomy: “It’s a tax for the pocket,” he responded.

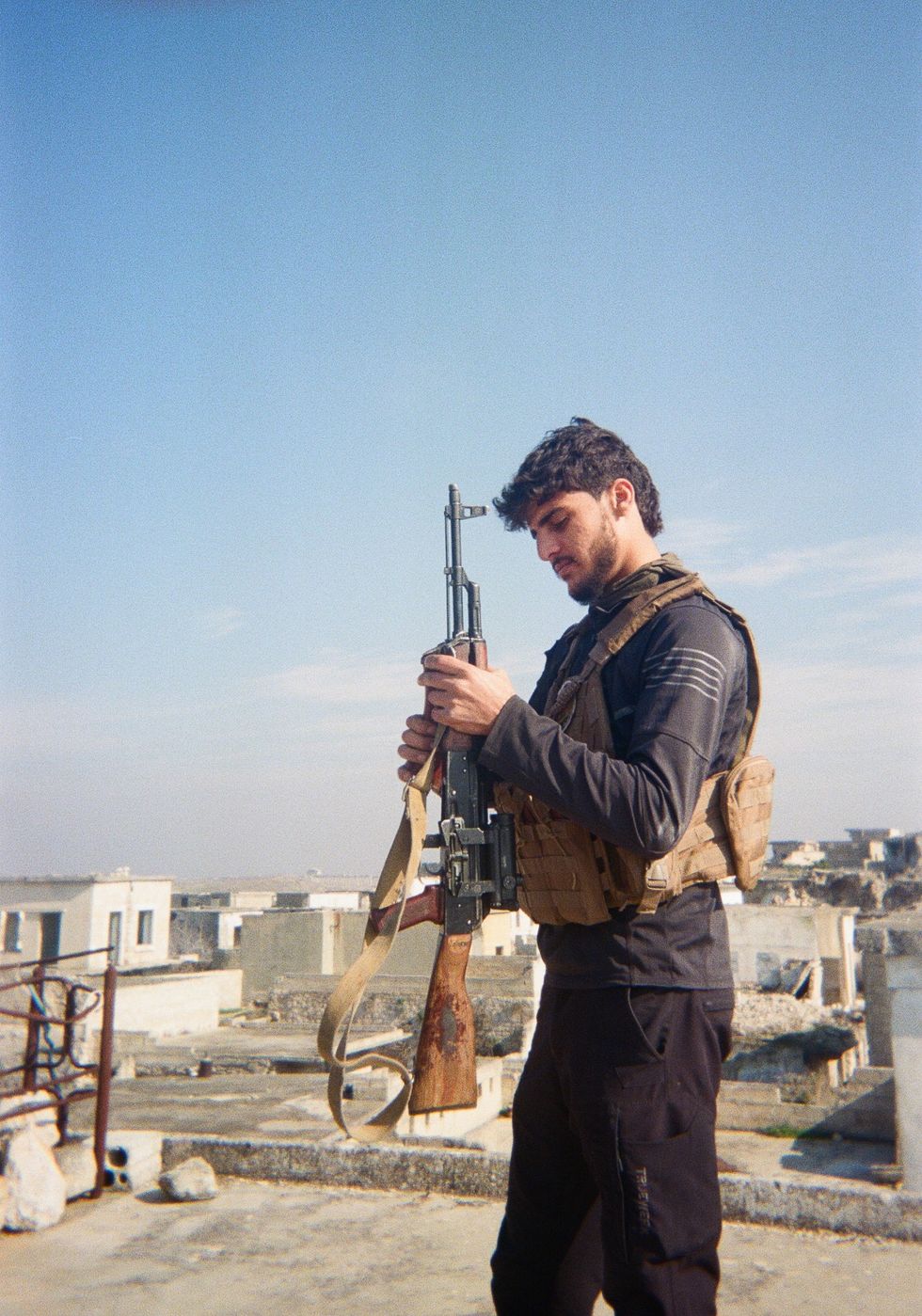

Upon crossing into Syria, our first sight was two adolescent boys, in military fatigues, practicing their marksmanship beside the highway. It would soon become a common encounter. That many armed revolutionaries were little more than growing boys, some maybe as young as 13, was obvious from their tenuous moustaches and their eagerness to impress foreigners. Some of these kids held up their rifles, proudly but clumsily, with unfamiliar hands that were still too small for this kind of toy.

Most of them seemed to have been deputized as street guards as more experienced fighters were needed elsewhere. Although some of them may have been actual soldiers—that would not have been too surprising. When children become targets in war or mere collateral damage—a pedantic distinction only textbook philosophers care about—they eventually reason: if every choice leads to death, better to die shooting back. That, or maybe something less calculated. Maybe the kids were just excited to carry a gun with the pretext of authority; nothing seems to initiate boys into manhood like some lethal power and a few entrusted responsibilities.

One morning in the Jewish Quarter of Damascus, I was briefly detained by an insurgent named Muhammed for taking pictures of veiled women outside a bakery. They were sorting through bread on top of car windshields, which were becoming opaque with flour dust, when I snapped the scene on my disposable camera. While we waited in the barracks for his superiors to question me, Muhammed passed the time by playing show-and-tell. He told me that his serrated knife was from America, that his Kalashnikov was from Germany, and that his combat pants were from Iran. When it came to demonstrating his gear, Muhammed was something like a cosmopolitan jihadist.

Later, when our conversation changed from material to metaphysical concerns, and Muhammed asked about my adherence to Islam, I was quick to disappoint my captor.

Then I confused him when he assumed that, not being Muslim, I must be Christian. “Actually,” I corrected him, “I am majnun [insane],” while twirling my finger above my ear as though scrambling my brains. The insurgent was shocked. He thought silently for a moment and then asked me to repeat the Shahada, which he recited for me in Arabic. The oath translates into English as: “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammed is His messenger.” I butchered the pronunciation, which didn’t seem to bother my officiant, because now, somehow, my detention for offensive photography had mutated into my one-sentence religious conversion. “You are now a Muslim,” Muhammed declared and then offered me a cigarette from his fresh pack labeled Elegance.

When his superiors arrived, they gave me a warm welcome but advised me against photographing religious women. It seemed obvious enough. But then, Syria can be a funny place when it comes to navigating public morality.

In the suburb of Jaramana, on the outskirts of the capital, a taxi driver pointed out that the many young women were widows-cum-prostitutes. He told us that USD 100 could buy one night of passion, which seemed relatively high considering lunch (with a drink!) had just cost me less than USD 1.50. At any rate, he said the market was for Iraqis, “who come from the desert and catch AIDS,” because “the Iraqis are donkeys.” Whether these insights were true or not—as many taxi drivers are keen sociologists (or zoologists, as the case may be with Iraqis)—I never got to the bottom of things. But what I did see on the sidewalk, where the whores advertised themselves, were conservative women carrying groceries. The sight recalled an observation made by Flaubert when he arrived on the shores of Alexandria, in a letter to his mother, about how Muslim women ventured into public, either completely covered or half-naked.

Such juxtaposition in dress and deportment caused me to wonder more generally about modesty among the Arabs. Did social conservatism come naturally to them? Or was restraint learned, perhaps over centuries, to compensate for intemperate desires? It was the chicken-or-the-egg dilemma of Islamic prohibition: which came first, the burqa or the breast? The answers to such questions were momentarily elusive but, upon reflection, now seem obvious and banal.

A universal logic underlies most human law, emerging not arbitrarily or thoughtlessly, despite the confounding influence of superstition and prejudice, but rather from the need to suppress some people with strong impulses. What one race inwardly strives against can be just as revealing of their nature as what they strive for—a fact to keep top of mind whenever emancipation becomes promoted as an essential good, since instincts are like genies coming out of bottles: once out, they don’t go back in so easily.

In the city of Homs, we met soldiers of the new regime on traffic duty. They were wearing all-black uniforms that were patched with the Syrian Salvation Government insignia and they claimed to have fought alongside Syria’s new leader, Al-Sharaa.

One terrifying aspect about local enforcement is that they all conceal their faces. The practice made sense when such men were regime subversives and designated terrorists, since keeping one’s identity undercover could stave off premature death. But now these rebels find themselves in control for the first time. My guess is that as the new government becomes accepted as the legitimate authority in Syria, this practice will soon stop, but until then, everyone continues to dress like insurgents from beheading videos. Not that the men in Homs were so different anyway.

These soldiers were very strict adherents of Sharia Law. When my friend offered them cigarettes, they gently declined his tribute, and when we asked about their musical tastes, they claimed to only listen to the Qur’an.

And, despite having fought against the Islamic State, the sources of conflict between the groups were political rather than ideological. “We don’t disagree with their aims,” they told us, “but the problem with ISIS is that they are too impatient.” These were surprising comments indeed. And their answers continued to reveal a degree of political maturity in place of the rabid fanaticism which one might expect. “We cannot thrust everyone into the Islamic Empire overnight,” one man continued; “change must happen slowly.” What change, exactly? One of the men pulled out his phone and showed us a picture: “This,” he said, showing us a little girl, a toddler, in full niqab.

This would doubtlessly provoke the emissaries of gender equality and progressivism into apoplectic rage. But then it wasn’t as simple as misogyny. These men cared only about dignity, not rights—which we in the West confuse as the proxy for respect and love. A conflation that naturally leads to surprises, such as when I asked these men about how they celebrated their successful insurrection. They responded, with an equanimity that’s more characteristic of sages than soldiers, “We first called our wives. They have been very patient with us.”

Because there were many women walking past us, in jeans and with their hair out, my friend asked what might await the Christian population. “In the meantime, they are fine,” one of them responded, “but we will deal with them eventually.” No doubt ominous words, and maybe even more sinister because they were said without anger or passion.

One of the younger men, Ahmad, was part of the offensive that claimed Homs, though he never shot a single bullet during the siege. He was excited by the victory but felt “deprived of the blessing of martyrdom.” Ahmad was now becoming bored with his new job, facilitating traffic, and he hoped to fight again for his Muslim brothers. A pedant could have interjected that, so far, his group appeared to have fought mostly against other Muslims, but that’s no way of making a new friend and especially a Salafist clutching a loaded machine gun.

Since the revolution was apparently without much violence, with Assad’s forces becoming so overwhelmed that most chose to abscond or surrender, some revolutionaries were convinced that the whole uprising was bloodless. A dubious proposition indeed. But whatever the facts were, many militants felt denied the glory of battle.

Concerning the Arab mindset, their insatiable propensity for war has been observed at many times throughout history. “As one caliph admitted,” to Arthur de Gobineau in the mid-nineteenth century, “the Arabs might possess military genius, but they completely lacked that of government and administration.”

Amending the caliph’s admission, one might say that Arabs derive their advantage less from military planning and more from martial courage. To find “genius” among desert dwellers would require diluting the word until it becomes meaningless. Not even general strategy or common sense are available to them. One soldier for the Free Syrian Army described an earlier (miscarried) attempt at insurrection, when rebels telegraphed their movements through posts on social media. Their eager indiscretion had the predictable effect of alerting the same enemy they hoped to catch by surprise.

But sometimes tortured logic can engender material success. The readiness to die and become martyrs could be why Arabs have remained historical people, while the rest of us, in the civilized world, have reasoned ourselves into suspended animation—a paralysis we’ve then reinterpreted, through our own transvaluation, as the triumphant “end of history.”

Except for the few soldiers trained by Turkey, most rebels considered the wooden stock and iron sights on their weapon as vestigial organs. I don’t think it was mere incompetence, either, which could have been corrected with one seminar on marksmanship; rather, their poor technique suggested existential indifference, which has no pedagogical cure.

Such demonstrations, to my eyes, became further evidence of Arabs prioritizing faith over form. And the strength of Muslim conviction, especially among jihadists, cannot be overstated.

Against every survival instinct that percolates into the secular mind, the jihadist considers leaving the battlefield intact no better a fate than leaving it in pieces. It’s an attitude that also seems to extend beyond themselves. We met several insurgents who had lost multiple family members in the war—often to Assad’s artillery fire, occasionally to Russian airstrikes—and who remembered them without showing trauma or grief. Instead, they seemed to have digested death like simple carbohydrates.

Across the Muslim world are many examples of this nonchalance towards death, or even its reappropriation from something feared to something welcomed. In his Letter to America (2002), Osama Bin Laden explained directly to Western audiences how jihadists reframed loss to their advantage:

As for us, jihad against the tyrants and the aggressors is a form of great worship in our religion. It is more precious to us than our fathers and sons. Thus, our jihad against you is worship, and your killing us is a testimony.

The last clause in that final sentence, “your killing us is a testimony,” seems like bending the rules to cheat the game: when jihadists win, they win; and when they lose, well, they also win.

But sometimes tortured logic can engender material success. The readiness to die and become martyrs could be why Arabs have remained historical people, while the rest of us, in the civilized world, have reasoned ourselves into suspended animation—a paralysis we’ve then reinterpreted, through our own transvaluation, as the triumphant “end of history.”

Islamists, who might otherwise lack our rational capacity and who might generally lag on the evolutionary timeline, have maintained their inclination for sacrifice—the force which propels an ethnos forward. They understand that the spirit of History must be propitiated with the continuous blood of martyrs.

These are the descriptions that inevitably make the epithet Islamofascism serviceable to polemicists who (very comfortably at home) agitate for wars in foreign lands. One shouldn’t be too surprised that they’ve made a portmanteau from contradictory terms. But there can be little truths inside a big lie. Modern Islamists understand what fascism espoused, that martyrdom and faith are twin pillars that undergird history; and when one falls, the whole structure comes crashing down. Remember that it was Mussolini (and not a Muslim) who said, “Those not ready to die for their faith are not worthy of professing it”—though its misattribution would be perfectly understandable.

At this otherwise unremarkable intersection in Homs, the jihadists poured us hot cups of yerba mate. They even provided us with the metal straws. What I appreciated the most was how unguarded they were with their opinions. There was no evasion or obfuscation or euphemism. They said exactly what they thought, without emotion, and seemingly without tailoring their answers to my status as a foreign writer.

At the end of our conversation, the men posed for my camera. However, they were first joined by an unknown chubby man, completely ordinary-looking and wearing a surgical mask. His presence diminished the gravitas of the scene and introduced some much-needed reality: even when lofty language can conjure up rich fantasies, it takes place on terra firma.

I noticed that every time martyrdom was evoked, in positive terms, many a serious journalist would furrow his brow in disapproval. But what these reporters dismissed as inscrutable nonsense was really one secret to pan-Islamic success.

Because, regardless of what one thinks about the substance of their desert religion, the jihadists have fought for their land, for their beliefs, for their God, and without so much as flinching at the sight of their own death. Yet these journalists thought their denunciations could break through and disturb such conviction. One must ask, if only rhetorically, who, between them, are more deluded?

In fact, rebels found our errantry more relatable than the professionalism affected by journalists. And no less surprising was that our casual approach earned far deeper insights, in mere days, than high-earning hacks, who had been there for several weeks. While we became “friends” with jihadists, exchanging stories and sleeping on their cold floors, journalists only left their hotels, like mosquitoes, to siphon off anecdotes until full, and then retreat to their swamp to contrive compelling stories.

Across from Assad’s favorite restaurant in Old Damascus, Naranj, a drunk German from the BBC had something heavy on his conscience.

He described an event that took place in Sednaya prison, which, under the Ba’athists, was allegedly the worst place to be incarcerated. His friend had witnessed a New York Times reporter stealing eight hard drives. After getting caught, the New York Times allegedly threatened bad press for the new regime unless the reporter was released.

It turned out to be much more than a rumor. I was leaked screenshots from one logistics group, where its administrators discussed the scandal with private outrage. Their thieving colleague had barred everyone from entering prisons and had increased general suspicion towards reporters. Through a bit of research, I also discovered the man’s identity.

For a fleeting moment, I felt inclined to reveal it. However, such tactics are the petty ways of journalists and, above all else, I could never do anything that might group me among them. By omitting the journalist’s name, I resolved to show him the mercy which he would deny others.

That’s not what was important about the story anyway. Much more pungent were the reticent witnesses—the other journalists present during the scandalous affair—who refused to give me further details, even when promised anonymity. They apologized and confessed to fears of becoming blacklisted by their publications, of being powerless to bureaucratic forces, of amplifying mistrust towards journalism—all excuses, and none that earned my sympathy. They instead betrayed the character of sniveling cowards and crude hypocrites. The same people who played moral arbiters—this week in Syria to censure Assad and condemn jihadists, next week elsewhere to issue similar verdicts—somehow lost their voices when confronted with housekeeping. Our paragons of transparency were now demanding some privacy. Please!

That toothless, illiterate, Islamic militants demonstrated more honor and better ethics … this provoked me into considering some dark justice: perhaps it was only fair that insurgents beheaded those reporters who delivered one thousand petty judgements on first sight; whereas the jihadist killed only men, the journalist executed the truth wherever he found it.

As posters of Assad were removed across the country, none were replaced by the visage of his usurper, Sharaa. Instead, the goalkeeper-turned-rebel-singer, Sarout, became the face of the new regime. While driving northwest from Hama, we unknowingly passed through the village where Sarout was fatally wounded and, therefore, promoted to martyrdom.

This was coincidentally on our way to see another singer, Khaled, whom my friend had found on social media. Not unlike the jihadists who only listen to the Qu’ran, some rebels listened exclusively to revolutionary chants. Perhaps when civil war lasts more than thirteen years, the constant need for inspiration and morale narrows one’s musical taste.

Khaled, though, could expand into other genres. He could give comfort as well as agitate for rebellion. During an assault on the nearest Christian village, Suqaylabiyah, he entered to find many townspeople sheltered inside a coffee shop. When Khaled breached the doors, gun in hand, the Christian occupants begged for his mercy.

Since the conflict had already claimed more than a quarter-million civilians, often as easy targets for petty revenge, these cafe-goers reasonably expected for themselves the same fate. But after Khaled relinquished his weapon, and sang mercifully to his terrified audience, their fearful tears turned into grateful weeping.

Khaled had fought in the Free Syrian Army since the beginning of the civil war. He recounted stories for us, including some about unlikely friendships made during close-quarter firefights, when only one concrete wall separated him from his rival belligerents. During these urban battles, combatants were often close enough to see each other’s faces, and soon they began to recognize one another, like how office workers might become familiar when they regularly share an elevator. Khaled told us other amusing anecdotes about how violent skirmishes could sometimes be punctuated by jokes, insults, and music. Even when trying to kill each other, boys will be boys.

Khaled then introduced us to some family members, uncles and nephews, who brought us into their newly reclaimed home. Like almost every other building in this town, it was bombed out, except that their house had contained many drums of diesel when it was struck. They showed us a video. It went up in orange flames and black plumes of sooty smoke.

One of the nephews had fought for Al-Nusra, the former al-Qaeda branch in Syria, which was founded by Sharaa. He showed us some coins, unearthed nearby, with Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine provenance. Tomorrow, the family would bring us to their digs. Although, as we would soon see, their system was less like archeology and more like tomb raiding.

We slept nearby on the floor of an abandoned café. I switched off our only source of warmth, a propane heater, before lying on my rolled-out mattress fully clothed. That initiative condemned everyone to shiver throughout the night, but I had to do it—I couldn’t fathom traveling all the way to Syria to then accidentally “wake up dead” from carbon monoxide poisoning.

We started our morning walking through an Ottoman caravanserai. In its courtyard were several gravestones of Roman legionnaires, crumbling from the effects of time and weather and neglect. We then visited the nearby medieval citadel. To the east, there were the ancient ruins of Apamea; to the west, the surrounding town was in rubble. The elevated fortress, too, was devastated. Its perennial military advantage made its structure an object of constant fighting. It was tragic to see a medieval town studded with bullet holes and crumbled from explosions. But there was also something poetic about the old fortress still being used for its original purpose.

The citadel was vacant except for one young man who was practicing his sharpshooting from upon the bastion walls. Behind a few glass bottles, which he placed in the distance as targets, was a well-inhabited village. That someone might survive decades of brutal conflict, only to be killed by a boy who carelessly shoots his gun for a little fun—does anyone imagine for themselves such an ironic death? And yet, the cemeteries are a testimony to God’s mordant hand, which composes the strange and syncopated music to our danse macabre.

At the Roman amphitheater, someone pointed out the previous locations of successful treasure hunting. Most notable were the gold rings, set with precious gemstones. These were most easily found, above ground in the sunbreak after a very heavy rainfall, when wet metal glimmered most radiantly. Such items were then sold for no more than USD 2,000 to Syrian middlemen, who then smuggled them into Turkey. Where the rings ended up, who knows?

Apamea was incredible and desolate. The Roman colonnade remained standing against all odds. In places, it still supported sections of entablature. On the ground were broken segments of pillar—of base, of shaft, and of capital—strewn about without a second thought.

We walked on the undulating mounts, under which ancient cities were buried. Our new friends from the night before demonstrated their excavation method. They first searched the landscape’s surface for rows of stonework, which were the possible capstones of subterranean walls. Eventually discovered, they then made deep trenches on both sides. Some pickaxes were used to loosen the dirt, which was then deposited into a wheelbarrow. The spoils were then dumped nearby and hovered over with a metal detector. Once the sensor was triggered, two piles were made. Each pile was then scanned again, so that the unresponsive one could be discarded. The process continued, exponentially splitting the mounds of soil, until the last reactive pile became small enough to scoop into one’s hands and sift through.

The revolutionaries have won for themselves the ultimate spoils of war: the burden of governance and rulership.

It was simple and it worked. We found shards of Byzantine glass, such as the bases of turquoise stemware, and several Greek coins, including one with Alexander the Great on the obverse side. My childhood fantasy of rogue archeology was finally being fulfilled. However, my excitement was also offset by our very crude methods. We destroyed more than we discovered. Watching these men excavate, it was painful to register how much of history was being regularly obliterated. In such places, where the ruins of higher civilization are plundered by ineducable peasants, one reevaluates Joseph de Maistre’s thesis that the earliest civilizations were near perfect and have only degenerated since. What once seemed to be an absurd argument now seemed compelling.

Some vases and urns were smashed throughout the process and revealed human bones. They were tossed aside as trifles. The careless way my friends handled garbage and relics and bone, evenly, evoked an image of post-apocalyptic monkeys, thoughtlessly exhuming human remains, unaware of the once-superior beings who came before them.

Of course, similar degeneration can be observed just as acutely over decades as across millennia, just as it can be recorded both domestically and abroad. If the man who effectively revived Islamic Jihad could see America today, Sayyid Qutb might revise the statement from his post-war visit that “America’s bounty and prosperity evokes the dreams of the Promised Land. The beauty that is manifested in its landscape, in the faces and physiques of its people is spellbinding.” Qutb was evidently not so modest as to avoid exaggeration or even biblical allusion, granted, but still America has declined, so dramatically, that the nation he visited might as well be ancient history.

From Apamea ruins, I brought home some coins and, from newer destruction, items that will doubtlessly become tomorrow’s artifacts. On the highway north from Damascus were many scorched cars, as well as several tanks that must have been ditched hastily during the uprising. We found one, completely upended, with its ammunition scattered on the ground like a prostrated corpse next to spilled groceries. One rebel, who must have seen us playing beside the tank, came over to yell at us. He said there were landmines all around. Bearing massive scars across his face, and missing one eye, we took his warnings as credible and left.

Of course, such boyish exploration could be dangerous but it could also be rewarding. On our last day in Syria, we scavenged through a checkpoint barracks just outside the Lebanese border. It had been left unguarded and seemed to have been untouched since its abandonment. It was our final chance to gather some war booty—or some souvenirs for friends and family. We found Syrian Army hats, military fatigues, Bashar posters, and one Hezbollah flag. Maybe it wasn’t exactly the rape and pillage fantasy one wishes for oneself, but since we couldn’t be hawks, we settled on being vultures.

And so, pan-Islamism has eclipsed pan-Arabism in yet another Arab country.

One wonders if Bashar now reflects upon his incumbency with some regret. A little soul-searching might recover the memory from 2008, when Gaddafi gave his stark warning to the Arab League, declaring, “Your turn is next.” In response to “the Mad Dog of the Middle East” and his rabid admonition, the Syrian leader broke into dismissive laughter. But then, less than two decades later, history laughed back even harder and turned the mad dog into a dead prophet.

We asked nearly every Syrian we encountered how they felt about the regime change. For Sunni Muslims, the largest ethnoreligious group, the eviction of Assad was farewell and good riddance. For others, especially the Christian and Alawite minorities, their fate was now balanced precariously between uncertainty and apocalypse. These were expected reactions.

Any public survey in the Middle East usually finds that individual opinion corresponds very consistently with tribal welfare, whereby political sentiment is merely a corollary to religion and ethnicity. Indeed, so much of the Syrian Civil War could be reduced to the clash of tribal politics with 7.62 x 39 mm. Not that such parochialism is unique to the Arab world. Everywhere are men who measure the world by the yardstick of their own circumstances, and who, like Nietzsche’s lambs, can only conceive of their betters as evil predators. Such is the world. However, what makes Syria especially interesting is their new leader, President Al-Sharaa. Much is still unknown about him, but he is demonstrating himself to be an altogether new breed of Islamic leader.

When I was there, Sharaa was still being called Jolani, though every day with less and less frequency—a name change signifying a more profound transformation, as Al-Jolani the insurgent was becoming Al-Sharaa the statesman.

Sharaa was born into a wealthy family in Saudi Arabia, who were originally from the Golan Heights (to which his nom de guerre, Jolani, is an explicit reference). He joined Al-qaeda in Iraq against the Americans during the invasion, fighting for three years until being imprisoned for half a decade. Once released, he started Al-Nusra in Syria, with the goal of overthrowing the Syrian Ba’athist government. During that time, he negotiated with other Sunni groups, such as the Islamic State, though he resisted subsuming his group into other transnational Islamic insurgencies. Even as a militant, Jolani demonstrated tact and cunning, with an ability to navigate political pressures. Not even apparent allies trusted him fully. He was once quoted as having “two faces” by the Islamic State’s second-in-command for his political duplicity. But his skill in negotiating and shapeshifting paid off and eventually positioned him as the head of Idlib’s government and the de facto leader of the revolution.

These are not mere details. They suggest a background and early life that follows the biographic formula of great leaders, unlike that of modern technocratic politicians. Without parallel, Sharaa is the apogee of Islamic insurgency, becoming an actual head of state, and, in some way, a vindication of Osama bin Laden’s holy war.

There is a near certain chance that I’ll be accused of writing an “apologia” for the enemy or reading too much into the psychology of barbaric people. While the charge of misplaced sympathy is wrong and stupid, there’s always the risk of claiming more to a situation than is truly justified—thus, I’ll avoid specific political predictions, especially in the Levantine desert, where certainty is even rarer than oases.

Yet a series of questions can be asked, such as: what is even possible in this part of the world and among these people? Can Sharaa lead the Arabs in escaping their condition? Most evidence suggests, no, the Arabs are stuck killing themselves over nothing—sand and scripture.

Even basic requirements for modern government, such as bureaucratic competence, continue to evade them. Our first errand in Damascus was to pick up our press credentials because, we were told, they would be necessary to travel throughout the country. Except that we never received them. The new Minister of Information had forgotten his laptop at home.

And at stake is far more than paperwork. The revolutionaries have won for themselves the ultimate spoils of war: the burden of governance and rulership. Of course, we should have some patience; the levers of power are handled clunkily at first, and like a new tenant blindly grasping for light switches in an unfamiliar home, it takes a while before things run smoothly. But can the Arabs eventually figure it out … if given enough time?

Again, Gobineau’s thoughts remain as relevant today as when they were first written: “Individually taken [the Arabs] are a noble race, but incapable of understanding the idea of the nation state, the idea of the system. Attachment to the tribe represents the extent of their capabilities.”

The Arab has particular limitations to his nature, as does every other race. But there is something even more damning. Islamism is fundamentally a populist and anti-elitist movement—a religious vehicle for peasant resentment against the intelligent and well-turned-out—so that the inherently provincial and blindly pious can relieve their sense of inferiority. The Syrian Revolution was waged for many reasons: some were intimate; others geopolitical. But the insurrection was also a successful slave revolt.

And such an upheaval has great implications.

Can the earth, which has seen so many prophets and gods, even raise another Apamea, let alone another Rome or Athens? Or has mankind become too old, too crippled, too close to its end, for civilizational splendors to ever be seen again?

Mike Mercury is collecting stories from around the world for his book in progress. Mike is focused on exploring why some people suffer decline and why others flourish, combining ethnography and socio-political analysis. He can be reached at mercurialmikemercury@gmail.com.

Mike Mercury