© 2026 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Inside a temple of Southern Literature, where the ghosts of Agrarian poets still wander the aisles.

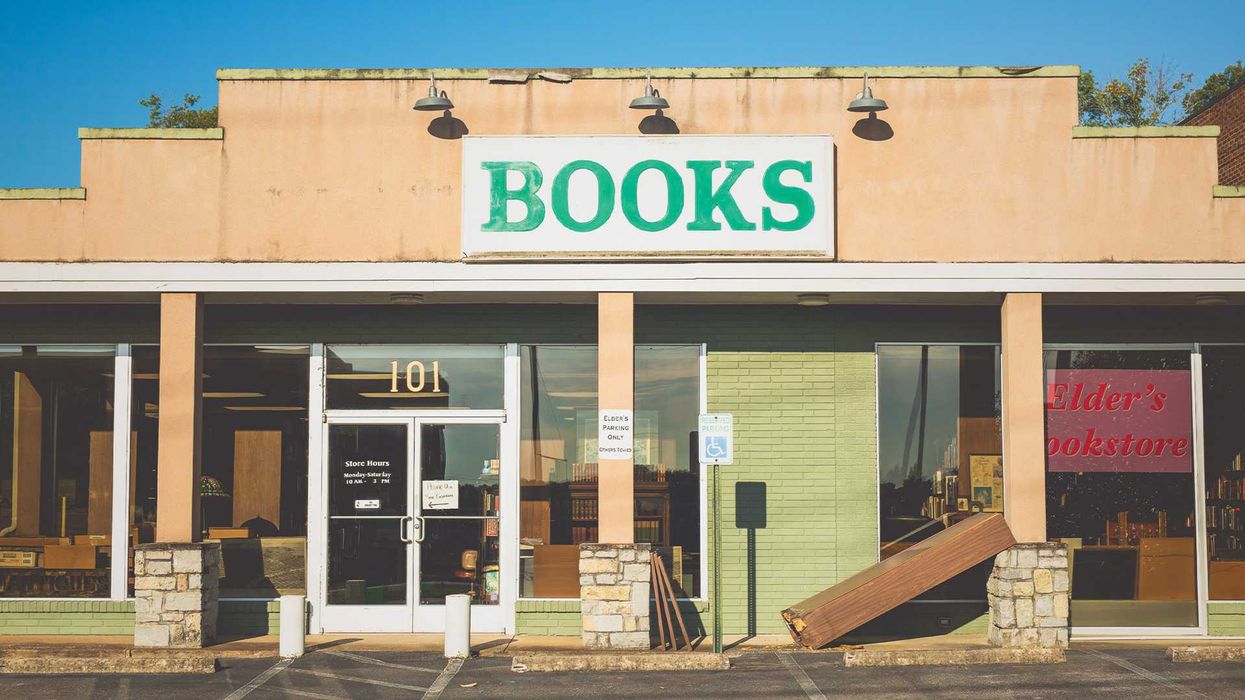

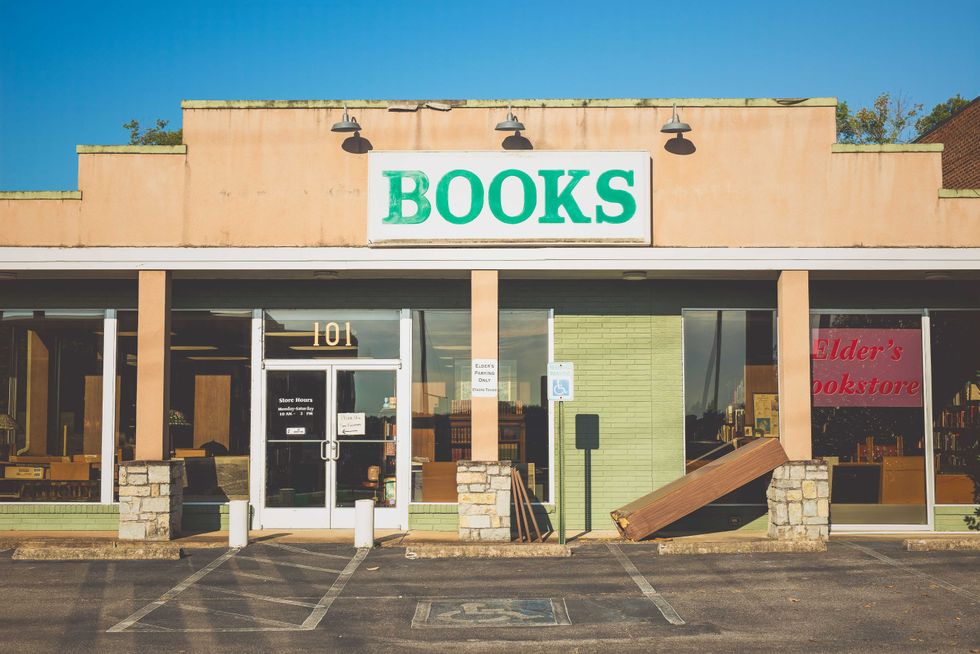

State route 155 carries its stream of cars past storefronts that might be anywhere. It circles Nashville for 35 miles, skirting the old Tennessee State Prison before surrendering its name to White Bridge Road. At 101 sits a repurposed mid-century mattress outlet. A sign above the street-facing windows reads in green letters against a white background: BOOKS. Between a fortune teller and bubble tea (that invasive species) is Tennessee’s longest-running bookshop, Elder’s Bookstore. A paper notice taped to the entry door requires pocket machines to be muzzled.

To the left, a few steps in, sits Randy Elder, the second-generation owner of the place. His desk is a Cumberland point bar where the current slows and the cultural sediment of a bookman’s trade collects. Scraps, notes, slips, and lists advance unchecked, creeping as vines will. Books crowd the edges. Cherokee myths, Scotch-Irish migrations, the roads of Nashville. Beside Mr. Elder, a young man hunches over a laptop, waiting on the next online order.

Elder wears his green polo loose, fabric soft as old cash. Limestone-colored hair. He never quite looks at you head-on. The smile hangs crooked. The look of a man who has seen collectors wince at the price or catch the Spirit at the sight of a long-hunted spine. The hands never quit, flutter-fidget-pick-shuffle, grabbing a book, nudging it, sliding another a quarter-inch to the left, flipping one open, then shut. The chain smoker’s rhythm without the smoke.

“Looking for anything particular?”

I mention the Fugitives, the Agrarians. Not the books, the men themselves.

He rises from the desk and walks. I follow. The light overhead is a hard civic white, the color of bureaucracy. The fluorescent tubes hum. I don’t know which note. I was born here. All the musicians came from out of town. We pass shelves that know the city’s three names: Athens, Music City, Neon Nowhere. The old city is still visible if you know where to look.

Athens

Beyond the desk stands the table, the center of the room. Glass-topped, its map spread wide, rivers like veins, counties etched in brown. Rolled maps jammed beneath like artillery shells. Over it all, the General’s portrait hangs—bearded, stern, eyes that follow the patriarch of the room.

Nashville’s fortunes rose with new men from the hollers and farms of Middle Tennessee and Southern Kentucky. Men whose fathers knew plows learned ledgers instead. They built themselves into bankers and insurance agents, Methodists and Presbyterians who set out to create a city of culture. By the time of the War for Southern Independence, Nashville claimed the title “Athens of the South.”

In 1897, they raised a White City, plaster temples celebrating a century of statehood. McKinley pressed a button in Washington; the current rode telegraph wires 700 miles to fire a cannon here. At the center stood their Parthenon, scaled exactly to the Athenian ruin. Progress itself, the crowd was told, had arrived. The Gettysburg Cyclorama drew steady crowds. Visitors examined Daniel Boone’s old flintlock rifle and Andrew Jackson’s dueling pistols.

This was the culture that shaped Vanderbilt University, where Randy’s father, Charles Elder, graduated in the 1920s. Latin and Greek anchored the early curriculum, creating a classical foundation that attracted serious students to Nashville. The university rejected provincial attitudes, seeking cosmopolitan faculty who could match Eastern institutions in scholarship and ambition.

Behind Elder’s desk is a cabinet of oak, maybe walnut. You’d call a buddy or two to scoot it six inches. At its corners, it has posts carved with feathered leaves that curl upward, its glass front catching every glare of those buzzing ceiling tubes. On the glass there’s a sticker: “I WAS ANTI-OBAMA BEFORE IT WAS COOL.” Behind the pane, books lean like drunks. Books that carried whole movements, whole generations. Elder reaches for The Fugitive: A Journal of Poetry.

Meanwhile, the music grows louder and always sounds the same, like the architecture around it—prefab, hollow.

The journal first appeared in 1922, born in a parlor on Whitland Avenue. The fruit of a group of sensitive young men gathered in Nashville parlors from 1915 through the 1920s. They read poems aloud, argued over rhyme and meter. The Fugitive would survive three years and eight months before ending. By December 1925, the contributors scattered toward university jobs, toward other cities, toward careers that demanded more than poetry could give.

Vanderbilt’s chancellor, James H. Kirkland, never subscribed; the English chair, Edwin Mims, urged them to send work to “Eastern journals.” Years later, Allen Tate himself walked into Elder’s, searching for The Golden Mean and Other Poems, the slim booklet he and Ridley Wills had printed in 1923. He left without one. The store holds a copy now. Their works line shelves across the room, a few even propped behind the glass of the “Obama cabinet.”

Mills went silent. The mule was driven out, the tractor drove in. Nashville was not spared the change. In 1930, Charles Elder opened a bookstore downtown. That year, Twelve Southerners set their names to a book, their defense against a world given to the machine. You can find I’ll Take My Stand now on Elder’s shelf, between The Fugitive and Who Owns America?

The Scopes Trial brought the world down on Tennessee. Reporters flooded Dayton, mocking its people as po’ White Tennessee trash. Nashville intellectuals watched. The wounds wouldn’t scab over. Blood pressure and tempers rose.

Ransom answered. Davidson answered. Tate and Warren answered—Fugitive poets joined by other Southern men, most tied to Vanderbilt. They became the Southern Agrarians, sometimes called the Vanderbilt Agrarians, sometimes the Nashville Agrarians. They named the machine as dignity’s thief. They named stewardship and tradition as the order worth keeping. Sons of small towns, sons of farms, sons of a South not yet erased—a South still holding what the nation had forgotten.

Vanderbilt was changing course. Latin and Greek fell away, the old order replaced by business courses and administrative salaries. Davidson stayed. The rest left. Tate sought aid and was refused. Warren, his course finished, went elsewhere. Ransom, denied his due, left at his prime.

Each departure scattered seeds. Ransom moved to Kenyon College, founded The Kenyon Review. Brooks and Warren drove south to LSU, started The Southern Review, turning it into America’s premier literary quarterly. Then LSU’s administrators killed it: money for deans, none for a Southern magazine. Andrew Nelson Lytle and Tate revived The Sewanee Review. These magazines shaped American literature for decades.

Yet the folkchain remains linked. Russell Kirk appreciated their work. Richard Weaver studied under them. M. E. Bradford came to Vanderbilt as Davidson’s doctoral student, called himself Davidson’s “disciple,” and spent his career writing about the Agrarians. Classrooms spawned more writers: Randall Jarrell, Robert Lowell, Peter Taylor, Flannery O’Connor, Harry Crews, and James Dickey. Their students’ students still lecture today in universities where Whitland Avenue means nothing. The genealogy stretches like biblical begats. Some say the Southern Renaissance began when Ransom walked into his first Vanderbilt classroom.

Music City

Next to a yellow mop bucket, a chair waits mid-aisle, exiled from some actuary’s cubicle. The old bookshop aesthetics are gone. What remains are the books themselves, visible in supermarket clarity. The air is scrubbed of mystery. The floor is checkered linoleum. Two colors alternating somewhere between oatmeal and cornmeal. I’m in the music section.

Jesse Ely Wills sat in the living room with the poets on Whitland Avenue, his cousin Ridley beside him. Across town their family switched on WSM, the “Air Castle of the South,” carrying fiddle tunes into living rooms across the region.

The Wills family changed the city’s name. Jesse’s father, William Ridley Wills, had cofounded the National Life and Accident Insurance Company in 1902. Twenty-three years later, as The Fugitive ended, his company put WSM on the air. “We Shield Millions”—slogan turned call letters. Jesse, still a Vanderbilt student at 23, joined the firm and never left. The Barn Dance followed. Then the Opry. Insurance wrapped in hillbilly music.

WSM’s first audience was made up of rural whites seeking factory jobs, fleeing farms the Depression had crushed. They crowded into neighborhoods that flooded with every hard rain; they lived in buildings without running water. Chamber of Commerce boosters sold Nashville to Northern manufacturers as a city with “cheap, docile labor” of “native, Anglo-Saxon stock.”

Nashville’s elite recoiled. “Low-class Cracker music,” they whispered in Belle Meade. They wouldn’t admit they listened, though their workers had no such shame. Athens had become Music City.

Charles Elder’s bookstore was at 4th Avenue North and Church Street. In 1957, Life and Casualty Insurance Company erected the L&C Tower on that exact spot—Nashville’s first skyscraper, tallest in the Southeast fora time. Elder’s moved to Elliston Place near Vanderbilt, where it became an institution.

Neon Nowhere

Bookstores dot the city, but they’ve got clerks with more pronouns and tattoos than books, rescue cats named Fauci with vaccine cards lurking about—their holiest sacrament, Banned Books Week. Meanwhile, the music grows louder and always sounds the same, like the architecture around it—prefab, hollow. The Athens of the South lies buried under pedal taverns and party buses. It’s hard to see with the sun reflecting off half-empty apartments with names like Albion, more spawn of Satan than seed of their namesake. This is the Neon Nowhere, a city with amnesia.

At Vanderbilt, more students speak Chinese than can name the Twelve. Born of Methodism, it once hired Christian men of tested character. Across the street, the Methodist church flies the rainbow flag. The prophets go unhonored now, though someone over there still appreciates the classics—the new Residential Colleges prove that much. Donald Davidson caught the Parthenon in verse back in 1935, already compromised by its setting, already diminished by men who didn’t know their Greek. Now you risk a beating there if you won’t play the jukebox for some vagrant.

A man pushes through Elder’s door, scans the shelves with airport urgency. “Y’all got anything on Hawaii?” Randy takes his name and phone number and promises to call if something turns up. The slip joins others grafted to his desk. At the airport, the hurried man might pause at the Fugitives Public House for high-proof syrup on the rocks, beneath letters that blaze orange plastic across the carpet, a parody of the name they stole.

I reach for one of the books on Randy’s desk. Nashville Pikes. The author: Ridley Wills II, Jesse Wills’s son. He died this year, back in January.

Yet there are people still around who know the way Hank did it. At Station Inn, you can hear that high lonesome sound. There are still Athenians about. You can find them over on the West End, where even the mosquitoes are more blue-blooded than my people.

Every city needs an Elder. A keeper who stocks Old Hickory biographies alongside hot chicken histories, who knows that the Fugitives weren’t outlaws and which singers were. State Route 155 carries me back into the stream. Behind me, the books, Randy at his desk, hands moving. Drive out there. Tell Mr. Elder you’re looking for Nashville. He’ll know which one you mean.

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

Chase Steely, a Tennessean and veteran, collects books and writes about them on his Substack, <a href="https://www.folkchain.org/">folkchain.org</a>.

Chase Steely

Chase Steely, a Tennessean and veteran, collects books and writes about them on his Substack, folkchain.org.

more stories

© 2026 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.