Fine Art via Getty Images

It’s a devilish question that raises various related — and equally existential — questions about art’s purpose and identity. After all, if we can’t even agree on what art is, how on earth are we supposed to judge whether the art made by AI is any good?

For those who haven’t heard the apocalyptic warnings about the algorithmic assault on human creativity or read about the lawsuits and scandals surrounding the new breed of generative AI models, they are sophisticated tools for turning words into visual images. Written instructions (called “prompts”) are fed through a multi-layered architecture of neural networks, ground into a kind of statistical powder, and matched via probabilistic correspondences to shades in individual pixels. The resulting image is the neural network’s interpretation of the words in the prompt, informed by its familiarity with hundreds of millions of other JPEG files.

The process by which these models generate images has an ancient analog: the Greek concept of ekphrasis. Meaning literally “to speak out,” ekphrasis refers to the rhetorical technique of describing works of art with vivid language. The most famous instance of ekphrasis is Homer’s depiction of Achilles’ shield in the "Iliad." When Homer describes the many emblems on the shield, which include “the inexhaustible blazing sun” and “noble cities filled with mortal men,” he is prompting the mushy gray nest of neural networks inside your brain to produce a detailed image of a “gorgeous and immortal work.”

What generative AI models make possible is the automation of ekphrasis. Rather than relying on humans to conjure an image in their mind’s eye based on a written description, these models do the work for us, turning written language into something we can actually look at.

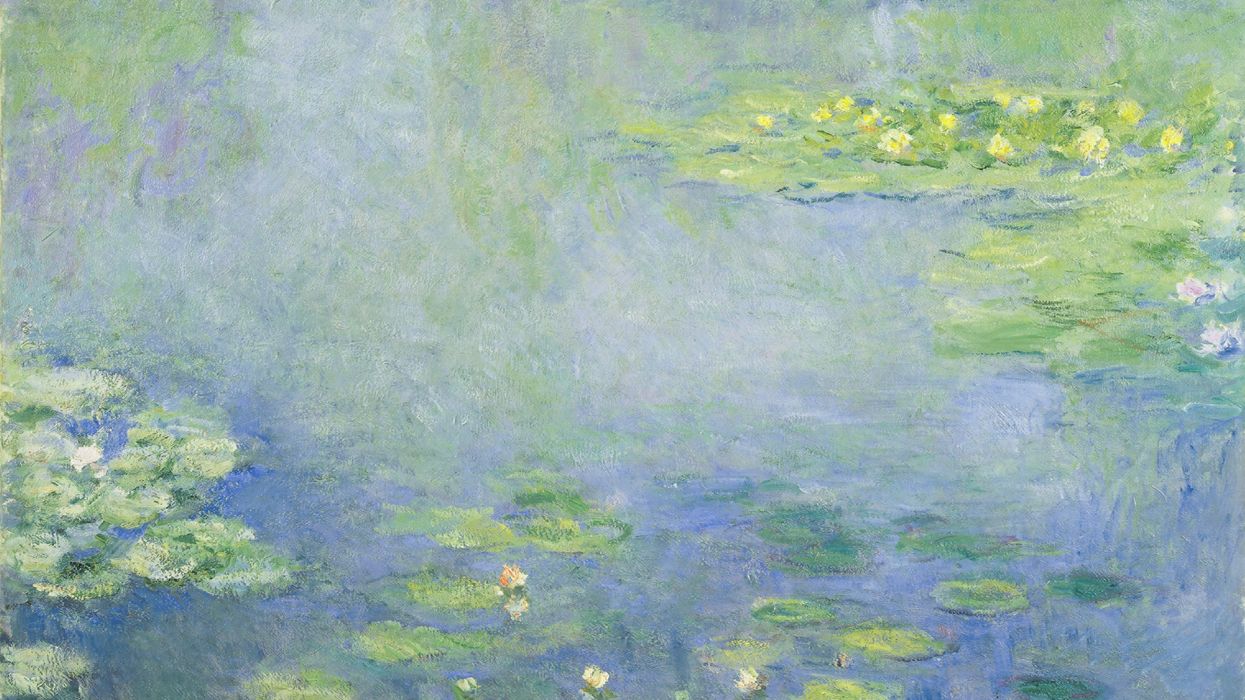

Many famous works of art have resulted from artisanal versions of such a process. Bernini turned Ovid’s description of Apollo chasing Daphne into a marble masterpiece that unfolds in four dimensions as you circle around it. Even the text of Dante’s "Paradiso," filled with heavenly experiences that the poet himself claimed that his eyes “could not sustain,” has inspired artists from William Blake to Gustave Doré.

One key difference between the above examples and the outputs of generative AI models is the nature of their respective prompts. For Bernini, Blake, and Doré, the words of Ovid and Dante were the prompts that fired their imaginations. For models like Midjourney or Stable Diffusion, the best prompts take a form distinctly different from classic literature.

Currently, summoning the finest images from these models means writing prompts with an esoteric syntax and vocabulary. If you want a minimalist image of a cat, including the word “minimalist” in the prompt will help, but repeating it five times in a row like a Buddhist mantra will help even more. Indicating that you prefer “4k resolution” or “volumetric lighting” can work wonders. So can specifying which rendering software style you would like the image to replicate. The end result can resemble an alchemist’s recipe of oddities that make little sense to humans but make perfect sense to an AI model:

RAW SF VFX 3d hyperrealistic 32K cosmic crashed cars sculpture gestalt Trisha Paytas composition 🌌🚀🌉🛣️highway spatial hair CHRIS lABROOY sculpture made of HAIR of 🛣️ Trisha Paytas CAR 🌌. Belin postneocubismo BY Andrew Thomas Huang. A goddess cyberpunk with a ram skull. beautiful intricately detailed Japanese crow kitsune mask and BIOTECH kimono:: OCCULTIST 🛣️ bubble CARs, epic royal background, big royal uncropped crown, royal jewelry, robotic, nature, full shot, symmetrical, Greg Rutkowski, Charlie Bowater, Beeple, Unreal 5, hyperrealistic, dynamic lighting, fantasy art

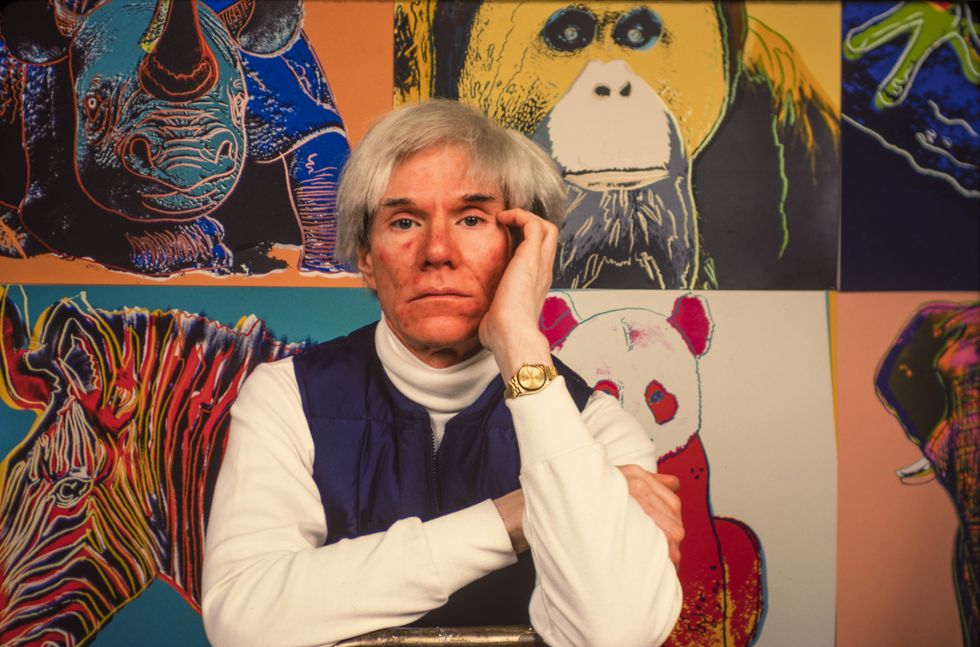

Those who specialize in communicating with AI models in this exquisitely bizarre idiom are called prompt engineers, and a stream of job advertisements for such positions has begun to emerge in the wake of the generative AI craze.

Despite the excitement surrounding prompt engineering, however, some argue that this peculiar way of addressing AI models will be short-lived. A chorus of tech-focused Twitter accounts have declared that “ prompt engineering will not be a thing.” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman appeared to concur when he recently announced: “I don’t think we’ll still be doing prompt engineering in five years.” Rather than a litany of seeming gibberish, these commentators argue that AI models will eventually become much more responsive to prompts written in conventional sentences. These strange machine dialects will wither away like other programming languages rendered obsolete by software advances.

Should such advancements come to fruition, the only constraint on the quality of the outputs generated by AI models will be the linguistic proficiency of the people using them. The heights of human eloquence, rather than any technical limitations, will determine the upper boundary of their potential performance.

This poses one small problem. For ages, humanity has rested on linguistic laurels, smugly satisfied with the ability — unique in all known creation — to weave together long recursive sentences made of distinct symbols. Now, technologies like ChatGPT have come along that evince the same ability, and the decline of our collective eloquence has suddenly become conspicuous.

Over the last several decades, the average American’s vocabulary has shriveled. This trend holds true for every level of educational attainment. Even though we spend on average two years longer in school than in 1974, we somehow manage to learn fewer words.

Already in 1999, David Orr coined the term “verbicide” to describe the unlettered speech of even his most gifted students. In his essay of the same name, he cites research suggesting that “the working vocabulary of the average 14-year-old has declined from some 25,000 words to 10,000 words” since the 1950s. This tendency has been going on too long to blame convenient bogeymen like smartphones or social media. But it does suggest a link with the proliferation of an earlier generation of household screens.

Not only have our vocabularies shrunk, but many fields of professional writing have come to be dominated by mind-numbingly dull prose conventions. One finds more flair on a tombstone than between the pages of peer-reviewed scientific journals. Ask a scientist, and he will often embarrassingly admit that these acronym-laced articles are frequently not comprehensible to the specialists composing their target audience. Meanwhile, at work, we are assailed by a grating corpspeak that memoirist Anna Wiener has memorably dubbed “garbage language.” This is the grandiose verbiage of company vision statements, full of buzzwords and pomposity but signifying nothing.

If prompt engineering is soon obsolesced by more capable AI models — less reliant on linguistic hacks and gimmicks — then the success of generative AI as a creative endeavor would seem to hinge on a linguistic tool kit rusted over with neglect. Currently, many of these models suffer from certain limitations. They often struggle to spell. They’re also not very good with hands and fingers. But these shortcomings will soon be fixed. And when they are, then it will be our unrelenting slide into inarticulateness that hobbles their potential.

To return to the question with which we began, the ability of these deep learning models to conjure beautiful works of art would seem destined to depend on our ability to compose beautiful lines of prose. It will be our capacity to carefully and evocatively describe the images we desire to see that will be tested, rather than the technology itself.

The 19th-century art critic John Ruskin’s advice to painters applies equally well to artists working with the generative AI models of the future. In his five-volume work " Modern Painters," he insists that “every class of rock, earth, and cloud, must be known by the painter, with geologic and meteorologic accuracy.” As each combination of elements in a landscape offers “distinct pleasures” and “peculiar lessons,” the quality of an image is partly determined by the artist’s knowledge of nature’s specificities. Accordingly, creating a desired effect with AI models will necessitate fluency in the many words we use to describe the world.

Consider Ruskin’s own description of J.M.W. Turner’s " The Slave Ship," first exhibited in 1840:

It is a sunset on the Atlantic after prolonged storm; but the storm is partially lulled, and the torn and streaming rain-clouds are moving in scarlet lines to lose themselves in the hollow of the night. The whole surface of sea included in the picture is divided into two ridges of enormous swell, not high, nor local, but a low, broad heaving of the whole ocean, like the lifting of its bosom by deep-drawn breath after the torture of the storm. Between these two ridges, the fire of the sunset falls along the trough of the sea, dyeing it with an awful but glorious light, the intense and lurid splendor which burns like gold and bathes like blood. Along this fiery path and valley, the tossing waves by which the swell of the sea is restlessly divided, lift themselves in dark, indefinite, fantastic forms, each casting a faint and ghastly shadow behind it along the illumined foam. They do not rise everywhere, but three or four together in wild groups, fitfully and furiously, as the under strength of the swell compels or permits them; leaving between them treacherous spaces of level and whirling water, now lighted with green and lamp-like fire, now flashing back the gold of the declining sun, now fearfully dyed from above with the indistinguishable images of the burning clouds, which fall upon them in flakes of crimson and scarlet, and give to the reckless waves the added motion of their own fiery flying.

I submit that a useful metric of a generative AI model’s performance may very well be its ability to capture the visual correlate of phrases like those used by Ruskin above.

The Ruskin test, if you will.

The oft-cited Turing test evaluates AI systems based on how effectively they can simulate a human being in conversation. If a person cannot tell he is talking to an AI, it has passed the test. The Ruskin test offers us a similar method of assessment. In this test, a person must compare a description of a work of art written by Ruskin with an accompanying image.

If the person cannot tell whether that image is the output of a generative AI model using Ruskin’s description as a prompt or a photo of the painting Ruskin described, then the model has passed the test. Any model that passes will have demonstrated its capacity to transmute human eloquence into great art seamlessly. The moment a model passes the Ruskin test, the age of prompt engineering will be over and a new era of eloquence will have begun.

An AI model that can skillfully render “reckless waves” or “green and lamp-like fire” will be one responsive to the most luxuriant expressions of human language. Such a model would reward eloquence, inspire it, and usher in a transformation in technical education. Courses in practical ekphrasis would supplement those in algorithms and data structures.

Disused words once coined to describe specific shades, landforms, or peculiarities of anatomy or architecture will need to be dusted off to better tailor future prompts. We shall need to reacquaint ourselves with the difference between vales and dales, between ash trees and elm trees, and between loggias and porticos. Repairing our vocabularies after decades of erosion will prove a key part of creating the best images these models can produce.

The advent of AI is only the latest in a series of historical traumas that have slowly undermined our sense of human exceptionalism. While Darwin showed that we share an indivisible genetic link with other animals and evolved by employing the same mechanism of natural selection, our notable language and art capacities still set us apart. Now a crowded field of neural networks has usurped these aspects of our unique identity.

What’s more, they have brought into stark relief the tragic fact that we failed to make good use of these talents. Responding to the challenges posed by these technologies will require us to undo a mechanization of thought that has flattened our forms of expression, making them frequently indistinguishable from algorithmic outputs. Doing so will require us to reconnect with our language and with the world that inspired it, to seek out the exact places where these technologies fail and where a revitalization of human eloquence might help them succeed.

Jason Rhys Parry holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Binghamton University and received a 2021 English PEN Translates Award. He tweets @JRhysParry.

Jason Rhys Parry

Guest Writer