© 2025 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

The cityfolk don't know what they're missing.

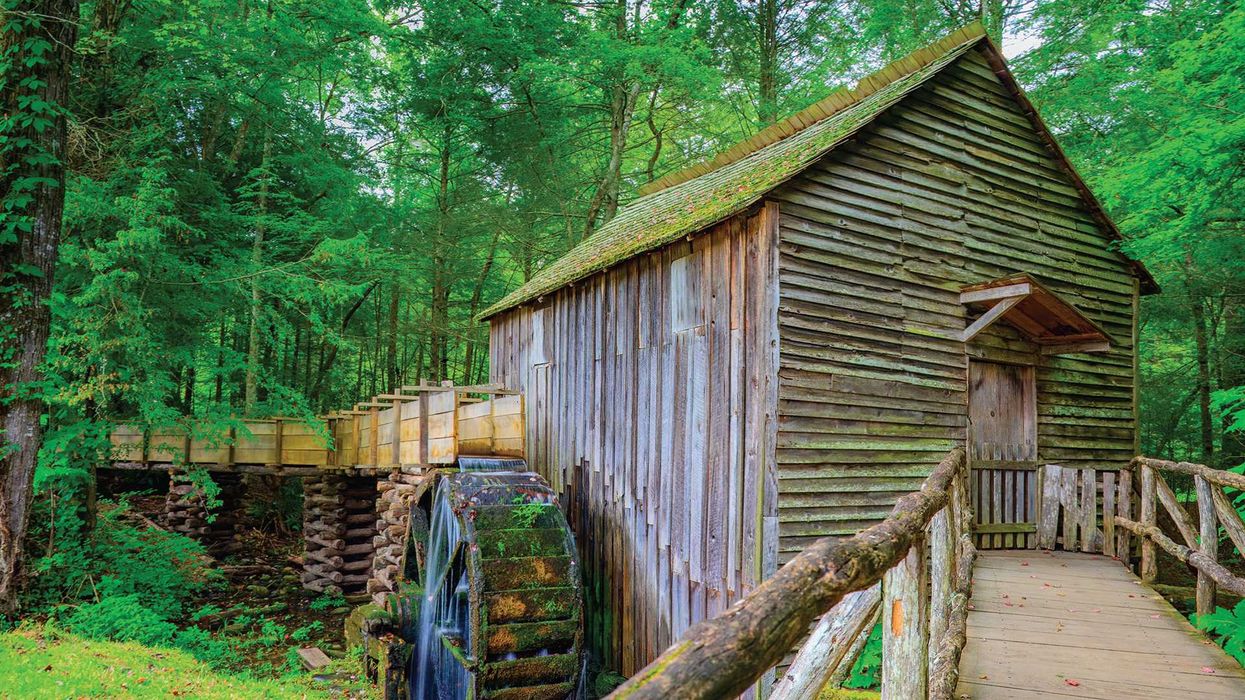

Crockett County has an ineffable quality only understood through experience. Robert W. Sills realized this on July 17, 2025, when he tried to break into a small farmhouse on Johnson Grove Road inhabited by a 12-year-old girl and her octogenarian grandmother. The home’s youngest resident took umbrage at Mr. Sills’s intrusion, then chased him out of the house and into a soybean field, where she tackled him and held him down until neighbors arrived to help restrain him before sheriff’s deputies showed up. The girl did all this barefoot. Despite the 24-hour news cycle’s relentless appetite for eye-catching stories, this particular tale never made the national news.

It’s no surprise that hinterland happenings get overlooked by popular culture. The vertices of mass communication in the United States lie on her ocean coasts. Cosmopolitan America’s relationship with agrestic America is one of a downward gaze, 30,000 feet aloft, en route from one important place to another. The perfunctory treatment overlooks the wild beauty and wonder of the places and people who live here. The common perception of rural folk as a distinct species also misses the fact that the same geopolitical and economic forces which threaten the country mouse also jeopardize the city mouse.

Crockett County’s population is just over 13,000 people. It’s a postbellum amalgamation of four different counties, created in 1871 to honor the area’s most famous congressman and frontier legend, Davy Crockett. The county’s primary economic staples were cotton and the railway at its inception, but over the years, both have been on the wane. The one thing the county has never lost in its century and a half of existence is the dynamic pioneering spirit of its namesake. Come what may, this small, rural, West Tennessee county is hanging in there like a hair in a biscuit.

If you want to know what’s happening in the southern part of the county, Bells Hardware and Lumber is the mainline to the zeitgeist. Bob Pigue and his family have owned the store since 1972. It’s a bit of a throwback to the frontier dry goods stores of yore. There, you can buy lumber and tools to build a new barn while taking delivery of a fifth-generation Glock 19 (the store is also a federally licensed firearms dealer). That’s not to say that Bells Hardware is anachronistic. The Pigues must avail themselves of every tool at their disposal to keep the small business afloat in a changing economy. Bob’s son John handles e-commerce and uses AI-driven analytics to help optimize wholesale purchases and monitor market trends. Bob thinks that convenience is what allows the store to survive in a world where big chain stores have driven thousands of family businesses out with economies of scale. John, on the other hand, thinks it’s specialization. “You can’t buy lumber off of Amazon,” he says.

Cosmopolitan America’s relationship with agrestic America is one of a downward gaze, 30,000 feet aloft, en route from one important place to another.

Bells Hardware is successful because of reciprocity: the Pigues invest in their community, and in return, the community invests in them. A few years ago, Bob led a project that revitalized a historic town theater that had been dormant for 17 years. Now it hosts high school plays and Christmas cantatas. The front counter of Bells Hardware is surrounded by stools where people sit to trade in what perpetually remains the hottest commodity in any small town: gossip. People will often come in, pull up a stool, and shoot the breeze while the Pigues dart to and fro, helping customers. In the decades I’ve known them, the only time I’ve seen Bob and John sitting down is during Bells City board meetings, where father and son serve the city as aldermen. While the hardware store has a folksy, Mayberry-like charm, the Bells City Council is a very different can of worms, or at least it was during the reign of Mayor Harold Craig.

Harold Craig was a former used car salesman who served as Bell’s mayor for 20 years. He was a good ole boy, an avuncular figure with a quick smile and a mischievous gleam in his eyes. When Craig first took office, he amended the city charter to officially classify the mayor as a city employee. Then he waited. Eventually, the board of aldermen turned over completely, and there was no one left who remembered Craig’s amendment. That’s when he struck. When it came time to propose a new budget, the mayor addressed the new city board with effusive praise for the city employees and all the great work they’d performed the previous year. He then recommended that all city employees receive a raise. The board assented, not realizing Mayor Craig was effectively arguing that his own salary be increased. He got away with this for a few budget cycles, then the board caught on—and scandal erupted.

When Craig’s stealth raises became public knowledge, the quiet town of Bells became a locus for regional news coverage. Every area newspaper and the lone regional television station descended upon the quiet town like locusts. The mayor greatly enjoyed the attention, hamming it up for the cameras during board meetings, slamming his folded pocketknife on the table like a gavel to quiet the raucous crowds that showed up for the must-see drama. The crux of the issue was a state law that forbade an elected official from giving himself a raise during a mid-term year. Legally, the issue with Craig’s self-largesse stemmed from the fact that he made it an annual event. When John Pigue asked, during one meeting, how many of the mayor’s raises were illegal, city attorney Jasper Taylor IV replied, “Let’s not say illegal, let’s say ‘unlawful.’” The Pigues and the rest of the city board were mortified.

Craig eventually returned his ill-gotten gains, but by then, the damage was done politically. The good people of Bells promptly voted him out in the next election. The last time I saw Harold Craig, he was at a gas station, fueling a brand-new white Chevrolet Z-71. I complimented him on his new ride, and he looked at me with that sparkle in his eyes and said, “The other day somebody said to me, ‘that’s a nice truck, Mayor,’ and you know what I told him? I said, ‘Hell, when you’ve stolen as much as I have, you ought to treat yourself once in a while.” He passed away about a year after that. No one who knew Harold Craig will ever forget him. Now, Bells has a new mayor and anew city board, and Bob Pigue says it’s the best board he’s ever worked with, which is a shame for people who enjoy a good yarn. Nothing in the world is more boring than effective local government.

Rural life in Tennessee is a hidden universe, invisible to the lens of mass media. The citified conception of places like Crockett County is a desultory parade of symbols: red MAGA hats, lifted pickups blaring country music, life obfuscated by the villainous patina of Old South romanticism. The coastal brahmins are blind to the vibrant current that runs through these small towns. Crockett County, like the rest of the world, is perpetually navigating the changing maze of the times, persevering as best as it can in its own uniquely wonderful way. Who knows what the future will bring? The only certainty is that the people here will brave whatever comes with the same self-reliance and courage as the county’s namesake, who famously once said “Be sure you’re right, then go ahead.”

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

Hamilton Wesley Ellis is a writer from rural West Tennessee.

Hamilton Wesley Ellis

Hamilton Wesley Ellis is a writer from rural West Tennessee.

more stories

© 2025 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.