© 2026 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

"I'm not putting my tin helmet on or hiding under a rock."

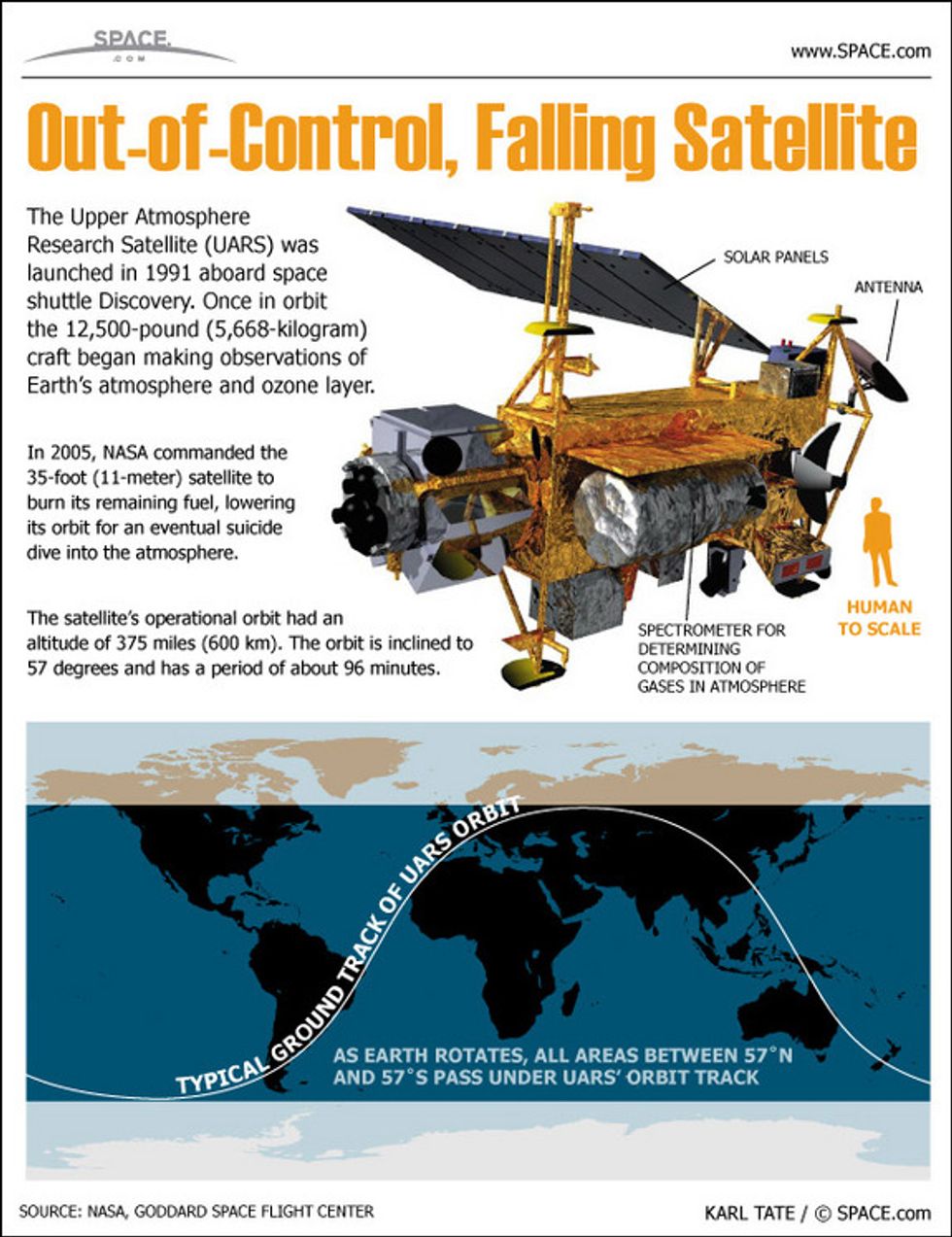

A six-ton satellite is hurtling towards earth. When will it land? Oh, well, sometime between Thursday and Saturday. Where will it land? Anywhere -- its strike zone covers most of Earth.

NASA scientists are doing their best to predict these whens and wheres but predicting something with a mass of about three compact cars is an imprecise science. It is already a day ahead of schedule than what scientists had predicted earlier, according to Space.com. If scientists predictions of where it lands are off -- even by a bit -- it could be the difference between landing in the ocean, which is what scientists are hoping for, or hitting populated ground.

If you live between latitudes 57 degrees north and 57 degrees south -- as far north as Edmonton and Alberta, Canada, and Aberdeen, Scotland, and as far south as Cape Horn, the southernmost tip of South America -- you could see a piece of UARS, the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite. Every continent but Antarctica is in the strike zone.

This video shows you the coverage of where the satellite could hit:

But don't worry too much. NASA says it will break apart into at least 100 smaller pieces bringing the odds 1 in 21 trillion that anyone on Earth gets hit. NASA says that most pieces will burn up before hitting land or sea, but about 26 of the heaviest metal parts are expected to reach Earth with the biggest chunk weighing about 300 pounds.

According to Space.com in a Q&A about space debris falling back to Earth, the during the last 50 years an average of one piece of "space junk" has fallen back to Earth each day. But no serious injury or serious property damage has been confirmed. This is probably because the majority of the planet is water and uninhabited land is more prevalent than you would think.

But, one thing to note is that if you do come across what you suspect is a satellite piece, do not pick it up. Although NASA says there are no toxic chemicals present, but there could be sharp edges. Plus, it's government property, making it against the law to keep as a souvenir or sell on eBay. NASA's advice is to report it to the police.

Jonathan McDowell, for one, isn't worried. He is in the potential strike zone - along with most of the world's 7 billion citizens. McDowell is with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

"There's stuff that's heavy that falls out of the sky almost every year," McDowell says. So far this year, he noted, two massive Russian rocket stages have taken the plunge.

As for the odds of the satellite hitting someone, "it's a small chance. We take much bigger chances all the time in our lives," McDowell says. "So I'm not putting my tin helmet on or hiding under a rock."

All told, 1,200 pounds of wreckage is expected to smack down - the heaviest pieces made of titanium, stainless steel or beryllium. That represents just one-tenth the mass of the satellite, which stretches 35 feet long and 15 feet in diameter.

When UARS was launched to study the ozone layer in 1991, NASA didn't always pay attention to the "what goes up must come down" rule. Nowadays, satellites must be designed either to burn up on re-entering the atmosphere or to have enough fuel to be steered into a watery grave or up into a higher, long-term orbit.

The International Space Station - the largest manmade structure ever to orbit the planet - is no exception. NASA has a plan to bring it down safely sometime after 2020.

Russia's old Mir station came down over the Pacific, in a controlled re-entry, in 2001. But one of its predecessors, Salyut 7, fell uncontrolled through the atmosphere in 1991. The most recent uncontrolled return of a large NASA satellite was in 2002.

The most sensational case of all was Skylab, the early U.S. space station whose impending demise three decades ago alarmed people around the world and touched off a guessing game as to where it might land. It plummeted harmlessly into the Indian Ocean and onto remote parts of Australia in July 1979.

The $740 million UARS was decommissioned in 2005, after NASA lowered its orbit with the little remaining fuel on board. NASA didn't want to keep it up longer than necessary, for fear of a collision or an exploding fuel tank, either of which would have left a lot of space litter.

Predicting where the satellite will strike is a little like predicting the weather several days out, says NASA orbital debris scientist Mark Matney.

Experts expect to have a good idea by Thursday of when and where UARS might fall, Matney says. They won't be able to pinpoint the exact time, but they should be able to narrow it to a few hours.

Given the spacecraft's orbital speed of 17,500 mph, or 5 miles per second, a prediction that is off by just a few minutes could mean a 1,000-mile error. It probably won't be clear where it fell until afterward, Matney says.

If it happens in darkness, it should be visible.

"If someone is lucky enough to be near the re-entry at nighttime, they'll get quite a show," says Matney, who works at Johnson Space Center in Houston, also in the potential strike zone.

Space junk in general is on the rise, much of it destroyed or broken satellites and chunks of used rockets. More than 20,000 manmade objects at least 4 inches in diameter are being tracked in orbit.

This video explains how fragmentation of objects in space occurs and how they are dispersed:

It's mostly a threat to astronauts in space, rather than people on Earth. In June, the six residents of the International Space Station took shelter in their docked Soyuz lifeboats because of passing debris. The unidentified object came within 1,100 feet of the complex, the closest call yet.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

more stories

Sign up for the Blaze newsletter

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.

Related Content

© 2026 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.