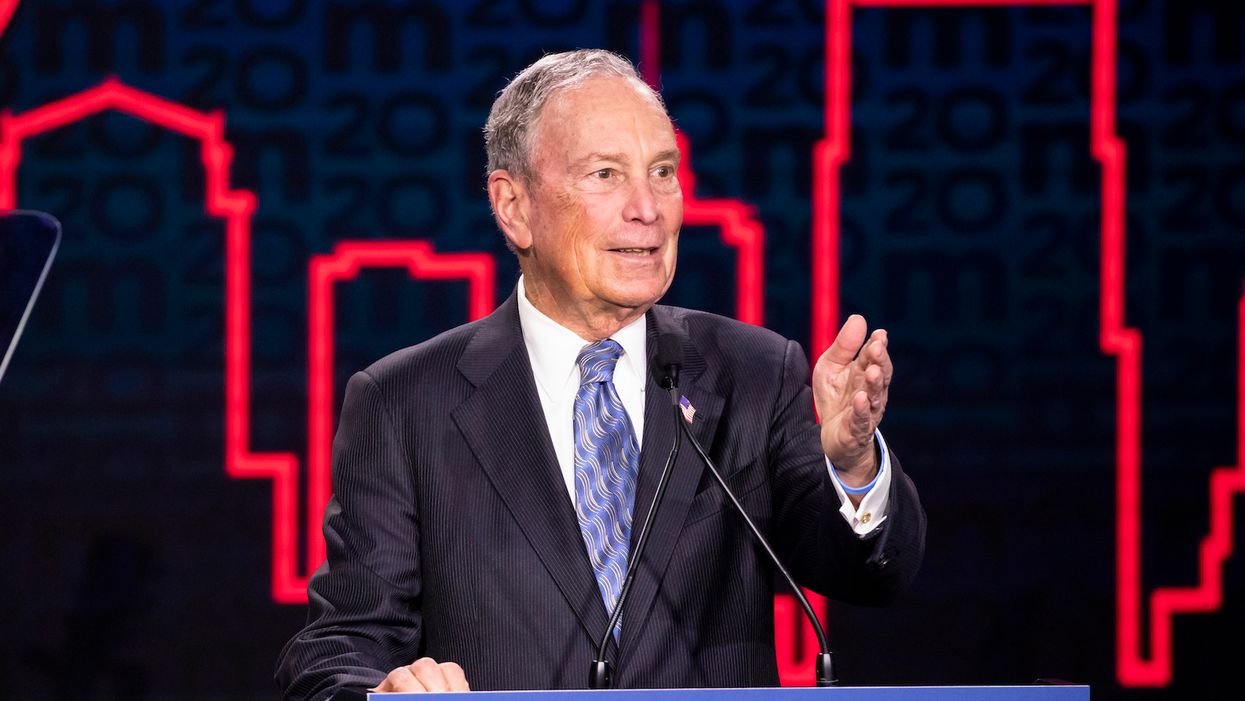

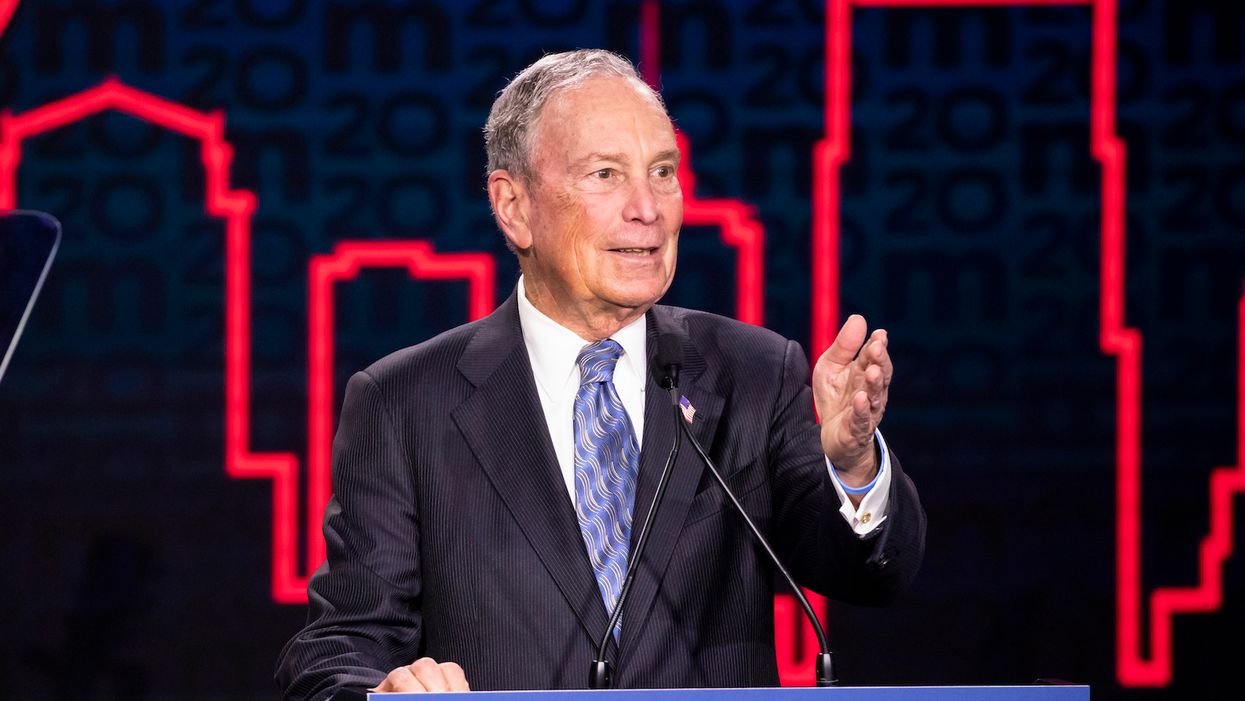

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg presided over the peak use of "stop and frisk" by NYPD. (Brett Carlsen/Getty Images)

The numbers are clear

When former New York City mayor and current Democratic presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg's racist comments about the stop-and-frisk policing method leaked this week, defenders of the policy quickly attempted to separate the racism from the method itself.

In a 2015 speech that he attempted to suppress from the public, Bloomberg said 95% of murderers are male minorities between the ages of 16 and 25, so police resources should focus on targeting people who fit that profile.

He brushed off the fact that a disproportionate number of those arrested for marijuana were minorities, calling it an "unintended consequence" of putting all the police in minority neighborhoods "where all the crime is."

In order to get guns out of these young minorities' hands, you have to "throw them up against the wall and frisk them" to discourage them from carrying.

One of the first arguments typically made in favor of stop-and-frisk is that it's constitutional. This claim is based on the 1968 U.S. Supreme Court case Terry v. Ohio, which established that police officers can stop-and-frisk someone without probable cause, if that officer holds a "reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime and has a reasonable belief that the person may be armed and presently dangerous."

It must be noted, however, that this ruling very specifically applied to searches for weapons performed on people reasonably thought to be a threat to the officer or others. It does not apply to possession of drugs — but Bloomberg readily conceded in the aforementioned speech that drug arrests are often the result of stop-and-frisk encounters.

Terry v. Ohio established that the frisk "must therefore be confined in scope to an intrusion reasonably designed to discover guns, knives, clubs, or other hidden instruments for the assault of the police officer."

A 1993 case, Minnesota v. Dickerson, expanded the scope of a stop-and-frisk to allow for the seizure of contraband, including drugs, detected by an officer in the course of a legal frisk. So, if an officer who is frisking someone for weapons under "reasonable suspicion" happens to feel a bag of marijuana, a warrantless seizure is justified.

In his concurrence with the Court's opinion in that case, the late Justice Antonin Scalia expressed concerns about the potential that allowing the admissibility of drugs from stop-and-frisks could encourage more frisks for drugs. This expands stop-and-frisk beyond the intent of Terry v. Ohio, which, again, was focused on frisks for weapons for the sake of the safety of the officer or others.

More importantly, Scalia directly questioned whether the concept of stop-and-frisk violated what the Founding Fathers intended when they drafted the Bill of Rights.

"I frankly doubt, moreover, whether the fiercely proud men who adopted our Fourth Amendment would have allowed themselves to be subjected, on mere suspicion of being armed and dangerous, to such indignity," Scalia wrote of stop-and-frisk.

Indeed, if Bloomberg's comments are any indication, Scalia was correct in his concern. And the statistics clearly show who the primary victims of this expansion are.

The New York Civil Liberties Union tracked stop-and-frisk demographic data from 2003 through the first half of 2019. The numbers revealed two overwhelming facts: A large majority of those stopped and frisked were either black or Hispanic, and even larger majority of those stopped were completely innocent.

In 2003, 160,851 people were stopped and frisked. Of those, 54% were black, 31% were Hispanic, and 87% percent of them were innocent.

Those percentages held pretty steady over the years, even as the number of stops increased dramatically until 2011, when NYPD officers under Bloomberg's watch stopped 685,724 people — 53% of whom were black, 33% Hispanic, and 88% innocent.

This problem didn't just plague New York City. In Philadelphia, data from January through June 2018 showed that despite criticism and lawsuits, blacks and Hispanics accounted for more than 80% of stops and 87% of frisks despite only constituting 56% of the city population. Only about 1% of frisks led to the recovery of a weapon.

Stop-and-frisk results in large numbers of innocent people being harassed by police. Stop-and-frisk leads to disproportionate numbers of minorities being harassed by police. Bloomberg wasn't making some wild, inconceivable comment that doesn't represent the truth of stop-and-frisk. He was describing the undeniably racist assumption at the heart of stop-and-frisk: Minorities are violent criminals, so the more we target minorities, the more violent crime we will prevent. If we have to frisk or arrest thousands of innocent or nonviolent people in the process, so be it.

One might still defend stop-and-frisk, or even Bloomberg's comments, by saying "Well, the crime rate did go down." But at what cost? It's disturbing how little regard someone must have for the rights and dignity of minorities, and all citizens, to feel that thousands upon thousands of unnecessary police stops represent effective policing, and are worth the result. And there is evidence that a significant decrease in stop-and-frisk encounters in New York City did not result in increased crime after all.

Another line of argument asserts that if you're innocent, you shouldn't mind if you're stopped and frisked by an officer every once in a while. It'll be over pretty quickly, and it's for the greater good of public safety, one might say. But the right to not be physically accosted in the street by police just because you look to an officer like you might be up to something should not be so easily discarded. People who are doing nothing wrong should not be subject to the disruption of having to prove their innocence to a suspicious cop.

Rights are important, even if the preservation of those rights makes it more difficult to achieve a goal. It's an argument conservatives make often against gun control advocates who would disregard the Second Amendment in order to, in their view, reduce the number of mass shootings.

Some people might feel safer knowing that police have broad authority to stop people based on the dangerously subjective standard of "reasonable suspicion." But statistics point to literally millions of examples in which innocent people felt much less safe because police officers treated them like criminals rather than people to be protected — often due, at least in part, to the color of their skin. If that's not racism, I don't know what is.