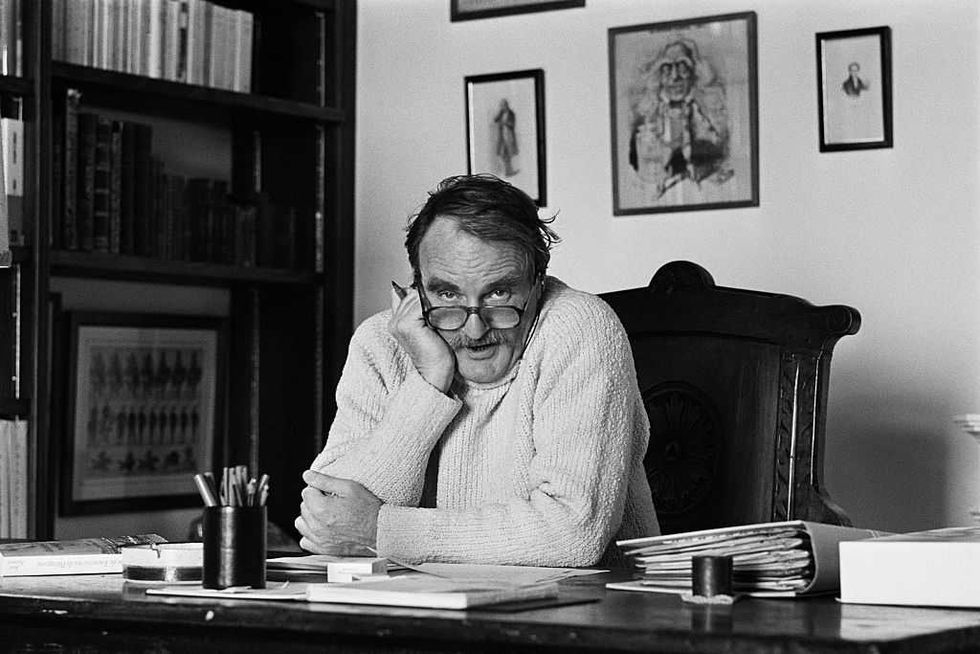

Photo by Bloomberg/Getty Images

A scandalous, nearly lost classic makes plain the stakes in the high-tech visa debate.

Jean Raspail’s "The Camp of the Saints" is one of those books you can’t mention at a dinner party without setting off a minor war. It’s been denounced, suppressed, and maligned as a hateful screed. And yet half a century after its publication, the book still pops like a gunshot. Why? Because it asks the question that polite society has done its best to avoid: What happens when a civilization loses the will to guard its own front door?

The novel is a fable, a satire, and a warning all at once. The plot is blunt: A massive flotilla of migrants sails toward France from India, while Europe’s leaders wring their hands, draft statements, and find ways not to act. The cast is drawn as caricatures — professors, journalists, bureaucrats, priests — each one a stand-in for the institutions that once anchored Europe but now serve as props for its decline. Raspail spares no one.

The poor on the ships are less his subject than the powerful on shore, who offer nothing but dithering and moral preening while their house is overrun. The book is brutal, unsubtle, and deliberately offensive. But it is also piercing, because it forces the West to confront its soft underbelly: its allergy to boundaries, its addiction to slogans, and its inability to say “no.”

If we want to preserve a middle class, we must demand that corporations train and hire our own graduates before importing replacements from abroad.

And it is why, surprisingly enough, it has something to say about our current debates over H-1B visas and high-tech immigration. Raspail describes hordes of the destitute; the H-1B program is designed for highly skilled engineers, scientists, and doctors. But dig deeper than the press releases, and you find the same theme: institutions playing make-believe, telling one story to the public while the true story unfolds in reality.

When the H-1B program was created, the pitch was simple. America, the world’s technological powerhouse, occasionally needs access to rare and exceptional skill sets. If a rocket company needs an aeronautical genius from Stuttgart, or a cancer lab needs a researcher from Mumbai, the law allows a narrow pipeline. The point was never to replace American workers but to supplement them, filling critical gaps while American talent pipelines caught up.

The reality, though, is something far different. Today, the H-1B program is dominated not by Nobel-caliber minds but by giant outsourcing firms and labor brokers who game the lottery system. They flood the application pool with tens of thousands of petitions, scoop up a massive share of the slots, and then rent those workers back to American companies at cut-rate wages. The result is not a pipeline for the “best and brightest,” but a labor arbitrage racket that undercuts American graduates while enriching a handful of consulting firms.

Even the most prestigious American firms have been caught using the H-1B program to displace their own workers, sometimes requiring those workers to train their replacements before letting them go. It’s the sort of ritual humiliation that would have made Raspail nod grimly: a civilization too weak to defend its own workers in its own labor market.

RELATED: Jean Raspail’s notorious — and prophetic — novel returns to America

Instead of nuclear physicists and neurosurgeons, we see armies of mid-level coders and IT staff — exactly the sort of roles American universities and trade schools could produce en masse if companies invested in them. Instead, corporations cut costs by importing cheaper labor, then spin it as a story of global competitiveness. The rhetoric is lofty; the practice is tawdry.

Here is where Raspail’s cold mirror matters. In his novel, Europe’s leaders never call things by their proper names. They drown reality in euphemism. The same is true today. Politicians and CEOs alike sell H-1B as a meritocratic jewel box, while insiders know it has become a vehicle for mass importation of mid-tier labor at discount prices. The tech lobby, one of the most powerful in Washington, spends lavishly to ensure that every attempt at reform is softened, delayed, or gutted. And so the system persists: a Potemkin policy that serves shareholders at the expense of citizens.

A visa program that actually admitted only the truly exceptional — the researcher on the cusp of curing a disease, the engineer pioneering a new material — would be defensible. A program that functions as a corporate back door for cheap labor is not.

Raspail also reminds us that admission is not an end, but a beginning. Those who come on visas should be expected to adopt the language, the civics, and the loyalty that make one a part of the American project. This is not cruelty; it is hospitality with standards. But when the bulk of visas are funneled through outsourcing firms, newcomers are less citizens-in-waiting than contract labor in transit, beholden not to America but to their sponsoring firm. That is not how you build a nation. That is how you hollow one out.

The truth is that the H-1B program, as currently run, is less a gate than a hollow archway — grand in appearance, flimsy in substance. It is sold as a crown jewel of American competitiveness, but in practice, it erodes wages, weakens training incentives, and mocks the idea of meritocracy. It is the sort of policy that Raspail would have recognized immediately: a symbol of a civilization that cannot even defend its own professionals in its own industries.

The armada in "The Camp of the Saints" is fiction, exaggerated and harsh. But the deeper theme — the failure of nerve, the surrender of sovereignty, the refusal to tell the truth about what is happening at the gates — is all too real. Today, it is not fleets of the poor but paper armies of visa applications, filed by corporate giants and labor brokers, that wash up at our shores. And our leaders, much like Raspail’s, prefer to hide behind euphemisms rather than face what they’ve allowed.

Literature earns its keep when it clarifies the stakes. "The Camp of the Saints" does not flatter; it does not console. It strips away illusions and forces us to see how quickly a civilization can collapse when it forgets to defend itself. Our immigration debate, particularly around H-1B visas, is in desperate need of that same clarity. If we want genuine excellence, we must close the scam pipelines and admit only those whose skills are verifiably rare and indispensable. If we want to preserve a middle class, we must demand that corporations train and hire our own graduates before importing replacements from abroad. Raspail’s novel insists on candor. It shows what happens when a nation replaces hard choices with soft lies.