Hakan Nural/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

We used to ask whether AI would one day sound sufficiently human to pass as one of us. But as Big Tech reshapes our world, we might ask if humans can sound sufficiently like the robotic voices displacing our reality to avoid trouble.

Back in the early days of the internet, about a year before Google was born, there existed a certain search engine called Ask Jeeves. Ask Jeeves perished in 2006 (first rebranded as ask.com, then vanishing into obscurity), along with many of the other search engines of those freewheeling early days when the internet still held out the promise of returning power to the people. Now, most of us ask Google.

But even when it comes to a question as seemingly basic as the pronunciation of the word “ask” itself, the sinister Silicon Valley behemoth does not answer our questions so much as it reshapes reality to conform it to its creators’ prejudices.

Sometime in the early 2000s, I had occasion to pal around with a bunch of grad students in Columbia University’s computer science department. Specifically, they worked in a subset of that department known as “natural language processing,” a branch of artificial intelligence that marries computer science and linguistics to give us, among other things, the kinds of idiot-savant talking bots (ChatGPT, Bard, Microsoft’s Copilot, etc.) that have shaken up our society within the past year.

I had a habit back then, as today, of amusing myself by correcting my friends’ grammatical errors. I do this in part because it is not considered nearly as much of a faux pas within the formality-loving, rule-abiding northern Russian culture in which my parents raised me and in part because I enjoy teasing friends about such matters even as I genuinely lament our growing collective apathy concerning written and spoken style and usage.

And so it came to pass that while I was at a soiree and doing my usual thing of correcting a friend’s bad grammar, one of the Columbia grad students in attendance, an effete and supercilious sort who had overheard the exchange, interjected, in his accustomed pedantic tone: “You do know, don’t you, that linguists consider grammar to be descriptive, not prescriptive, and there is no ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ way to say things?” My response was something akin to, “Oh, yeah, sure, I understands, thanks-you very muchly.”

Our collective apathy in the face of egregious grammatical errors was one thing. But when Google starts deliberately normalizing blatantly backward locutions, that significantly ups the ante.

And that was the end of that particular exchange.

In recent years, we have heard many such arguments from authority in a variety of fields in which people who play the role of journalists on TV and in print rely on some variant of “experts say,” “experts believe,” or “97% of experts agree” to short-circuit debate. These ex cathedra formulations often serve to paper over hotly contested matters and conceal ignorance and/or sloppy thinking, and it would, I think, be a good thing for all concerned if we made a routine practice of explaining arguments and laying bare evidence, at least by way of citation, rather than leaning on authorities. If we never again have to read the New York Times soliciting a quote from Harvard’s Frank Hu to demonize saturated fat and promote “heart-healthy” industrial seed oils or read another Katherine J. Wu-penned article in the Atlantic drawing on the alleged consensus of “experts” to promote state-sponsored, Big Pharma-boosted COVID fearmongering and disinformation, we will all be better for it.

The grad student who reprimanded me all those years ago by drawing on the authority of “linguists” is a prime example of what I am talking about, and I have occasionally thought about his pronouncement as I’ve watched the deterioration of speech and writing roll on over the years. Like other questions as to which no objective truth exists — all sorts of moral norms and standards of appropriate dress and behavior — the rules of grammar are determined by long-standing traditions as iteratively modified by prevalent social conventions.

But just as for these other conventionally determined matters, that there is no divinely decreed, unchanging Platonic form of proper English grammar does not end the inquiry. Nothing other than convention tells us that on a hot summer day, we should put on clothes before going out in public. Nothing other than convention commands us — at least in the West and in Eastern Europe — to eat with silverware rather than our hands and to cradle these implements with our fingers rather than grasping them in clenched fists.

Closer to the matter at hand, nothing beyond convention dictates that we should continue to spell any given word one way rather than some other way that might even be far more intuitive than doozies like “queue” and “phlegm.”

When we eat like barbarians, cannot spell, and permit egregious errors when we speak, we may not be violating any sort of God-given law, and yet we are violating important social rules and, as such, branding ourselves as uncouth and uneducated rubes. Children are taught these rules and conventions in school and at home so that they can grow up to thrive in a variety of social and professional environments as adults.

More recently, however, the same brand of toxic wokeism that has infected much of the rest of our lives has worked to undermine the teaching of such conventions, deeming them racist or “white-normed.”

As in other cases, academia’s left-wing monoculture has concocted apologias for these onslaughts, arguing that what appear on the surface to be grammatical errors are actually just manifestations of alternative dialects, such as African-American Vernacular English, within which a sentence such as “She don’t know what she done cuz she ain’t done nothin’ worth doin’” is perfectly correct. The speakers of such dialects, this story goes, communicate in this manner among themselves but are able to — and, indeed, forced to — “code-switch” into the standard American dialect to conform in white-dominated spaces. But to require such conformity to white norms is racist, we are told.

A generation hearing aks spoken by our increasingly automated voices of authority will come to conclude that it is just another acceptable alternative.

Far from universal among black Americans, however, “code-switching” is primarily something only people who grew up in families of low socioeconomic status but then received a good education can do. People who live their lives from start to finish in ghettos obviously cannot suddenly drop the double negatives, systematic misuses of subjective and objective pronouns, and predictable simplifications that drop certain verb conjugations, among other such errors common to uneducated speakers of English of all races, and start wielding the king’s English.

And it is hardly racist to urge all uneducated people, regardless of their race, to get an education and master various mainstream social conventions, whether these be how we dress, how we eat, or how we speak. Such norms are necessarily dictated by the majority, as guided by traditions and historical practices, but that doesn’t make them racist or, in any respect, wrong. Revering shared traditions and striving toward universal standards give us our sense of communal belonging, of being a part of a single society within which we can feel invested and included by partaking in these implicit codes evolution deploys to help us distinguish our countrymen from strangers among us.

Google, however, seems to have taken a different view.

I make somewhat regular use of an app in which I share articles to have it read them aloud to me while I go about various mindless daily chores. The app employs Google-generated text-to-speech voices. Sometime in mid-October, I began noticing that it had started pronouncing the word “ask” and all conjugations thereof as “aks.” Because I usually listen to text at a sped-up clip, I thought, at first, that I simply have to be imagining this. I slowed down the speech-generation rate to its natural pace and then even to half-speed. No, shockingly, I was not imagining this. Well, surely, I thought, this is some temporary glitch that will be remedied in a day or two.

Some two months later, here we are. No remedy seems to be forthcoming.

Curious to see if anyone else had encountered the issue, I came upon this Reddit discussion of the problem. Although it contained only a few posts, it consoled me to know that if I had entered the Matrix, at least I was not alone. On a Google Cloud community forum, I found another voice in the wilderness pleading with Google to correct the issue. The post was from October 17, having been met, as of this writing, with no responses whatsoever.

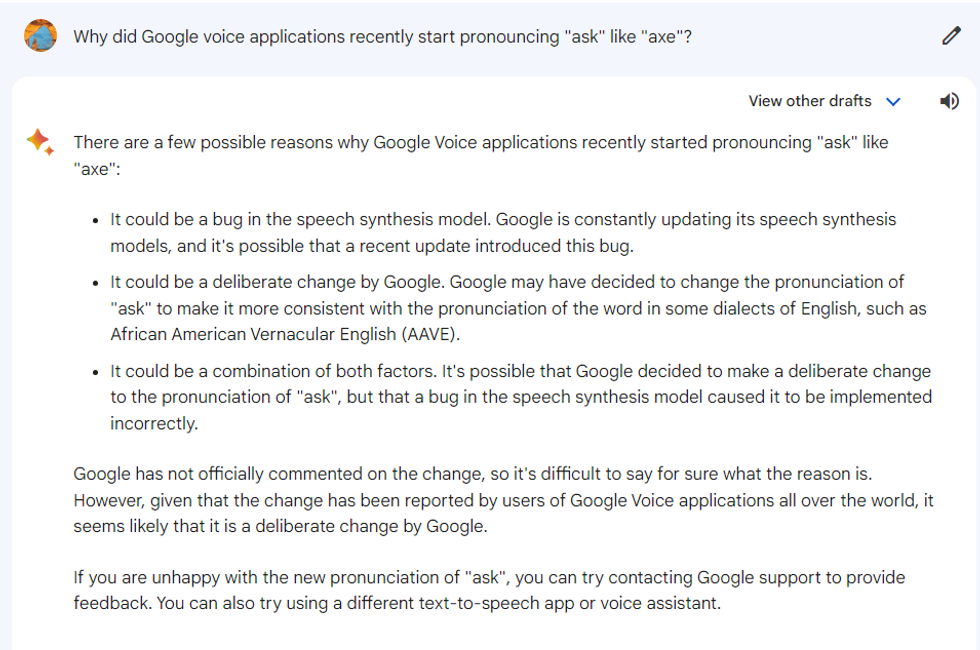

I decided to try asking (aksing?) Google’s Bard to shed light on the matter. The depressing answer I got was that “given that the change has been reported by users of Google Voice applications all over the world, it seems likely that it is a deliberate change by Google,” and that it was possible “Google may have decided to change the pronunciation of ‘ask’ to make it more consistent with the pronunciation of the word in some dialects of English, such as African American Vernacular English (AAVE)”:

I was still not fully recovered from the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s decision to have people with some of the most grating, most thickly New York-accented voices around — Whoopi Golberg, Jerry Seinfeld, Awkwafina, etc. — making announcements on the New York subway, and now here was Google engaging in an exercise worthy of a Stalinist re-education camp or the Jacobins’ renaming of the months of the year.

Our collective apathy in the face of egregious grammatical errors was one thing — I feel steam blowing out of my ears when the white-collar professionals in my midst keep talking about some opinion that’s shared “between my wife and I,” an error that got its fittingly ignominious public stamp of approval when Bill Clinton spoke about the Lewinsky affair being “between Hillary and I” — but when Google starts deliberately normalizing blatantly backward locutions, that significantly ups the ante.

Here is one of the most powerful corporations on Earth, in essence, flipping the bird to civilization and telling us that because some less-educated black people pronounce “ask” as “aks,” we’re going to reshape reality to accommodate them.

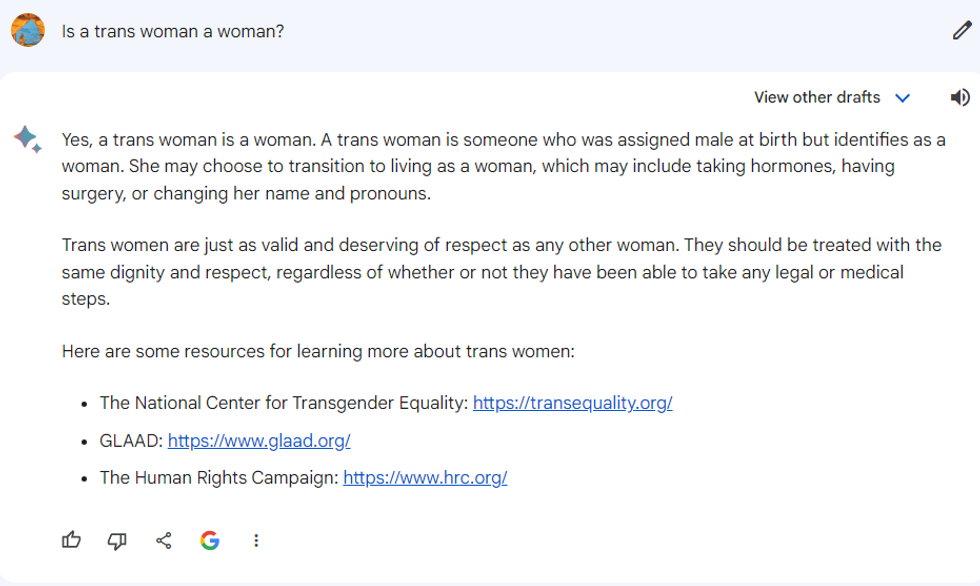

This is far from the first time we have robotic voices trying to conform our reality to their ideological fantasies. Here is the unequivocal, 60% consensus-defying answer Google’s Bard gives when asked if a trans woman is a woman, after all:

More broadly, research from New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology professor David Rozado has shown that Bard’s responses to a range of salient political queries (such as those typically asked on political orientation quizzes) indicate flagrant left-wing bias. Compared to this, mangling the pronunciation of “ask” seems relatively innocuous.

In important ways, however, it is also far more insidious. The 60% of us who do not buy into the absurd trans-woman-is-a-woman fantasy will have no trouble recognizing and rejecting Google’s propaganda on that front. On the other hand, ask versus aks is not some hot-button political issue that will readily register. It is, rather, the equivalent of a devious cheater shifting a pawn on the chessboard by a single square, knowing full well that his amateur opponents will not notice the shift until its devastating long-term ramifications come to fruition in the endgame.

A generation hearing aks spoken by our increasingly automated voices of authority will come to conclude that it is just another acceptable alternative, and then the next generation will grow up hearing aks as the default setting, with only a few old codgers and odd ducks playing the part of antediluvian holdouts.

And this, the linguists will tell us, is just how the natural evolution of language goes. Except that nothing about this particular process was natural. It was, instead, Google puppeteering us all the way.

Furthering the cause of “antiracism,” I fear, is only a ready-made justification Google will advance if it is ever called to comment on the change, while the underlying purpose may be more sinister. The subtle shift in the pronunciation of a single word may well be only a trial balloon. And even if Google reverses the change before long, the point will have been made. The experiment will have been successful, proving to the powers that be that, precisely as they suspected, when they begin to manipulate first the minor and later even the more consequential pieces on the board, hardly anyone will notice.

The question we used to ask — the one put to us by the famous Turing test — was will we ever be able to get AI to sound sufficiently human to pass as one of our own? But as the titans of Big Tech continue to play their long game to reshape our world, bit by bit, the question we will all soon find ourselves aksing is a kind of counter-Turing test that will be administered, even if implicitly, to one and all: Will we humans be able to sound sufficiently like the robotic voices displacing our reality to avoid revealing ourselves as dissenters and nonconformists in need of re-education?

Alexander Zubatov