Return Illustration

Why are we constantly forced to prove we're human?

A team of researchers at Carnegie Mellon University developed CAPTCHA, a contrived acronym for "Completely Automated Public Turing Test to Tell Computers and Humans Apart," in the early 2000s. CAPTCHAs meaningfully distinguished human and bot activity online for the first time. This advance curbed automated scourges of the internet, such as the mass creation of spam email accounts and illegitimate answers in online polls, and they remain an essential tool that makes the modern internet usable today.

So I decided to introduce a challenge for myself: Refuse to complete CAPTCHAs, in a refusal to prove my humanity to a computer.

But the computer scientist John Langford, who helped create CAPTCHA twenty years ago as a graduate student, is surprised they have lasted as long as they have. "I kind of expected machine learning to eventually succeed in making CAPTCHAs not a thing," he told me in an interview. "But that hasn't fully happened yet."

Instead of disappearing, CAPTCHAs have become more complex and more prevalent. It seems one can't go a day on the internet without needing to solve one.

So I decided to introduce a challenge for myself: Refuse to complete CAPTCHAs, in a refusal to prove my humanity to a computer. I understood the purpose of CAPTCHAs was noble and made the internet a better experience by reducing spam and preventing bots from buying up all the concert tickets, for instance. But still, I wanted to try. In the meantime, I would try to figure out why CAPTCHAs were still around and what their evolution may suggest about the future of the internet. As I dove into the story, I saw another wrinkle: how labor and AI may interact.

In the early 2000s, the internet had a problem: As spammers got better, they were able to write programs that could create countless free email accounts on services like Yahoo! Mail in seconds. This led to an explosion of spam.

A team of graduate students at Carnegie Mellon – Luis von Ahn, John Langford, Nicholas Hopper, and their adviser, Manuel Blum – tried to come up with a solution. The group knew they needed some way to differentiate humans from computers online. However, the test needed to be solvable by every human and have a low success rate by computers.

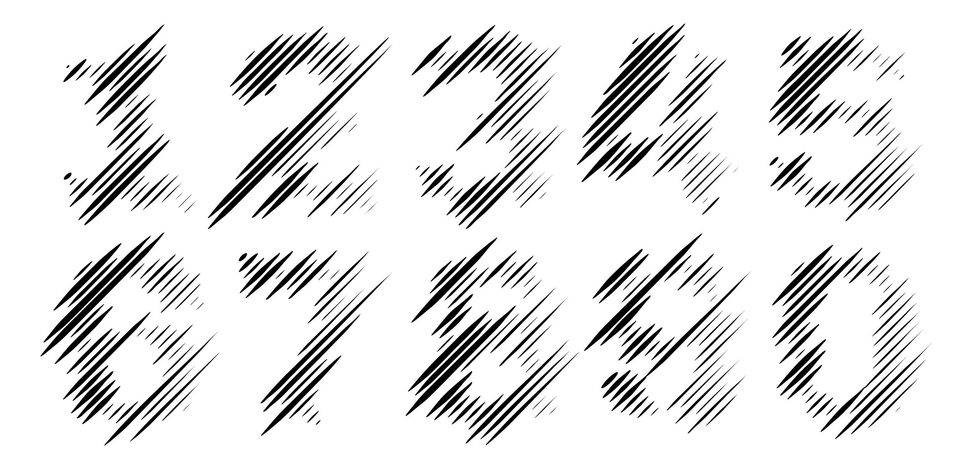

Eventually, the team settled on text recognition. They would distort an image of a word and ask the user to identify it. This worked much better than previous experiments: Computers were terrible at reading distorted text. Meanwhile, even if they didn't know what a specific word meant, humans were much better at identifying what letters were present. One didn't even need to be literate to solve a CAPTCHA, because it just required a person to match the letters on the screen to the letters on a keyboard.

The test went into effect at Yahoo! Mail and was quickly used millions of times daily. Over the next decade, however, a few things happened. First, Google bought an updated version of the technology called reCAPTCHA to digitize vast amounts of old text. By serving each user two words – one artificially distorted and one from an old New York Times article – the computer could transcribe those articles using unwitting human participants. Second, though, computers got better at identifying distorted text – to such an extent that, according to a 2014 internal Google study, AI could read the most distorted CAPTCHAs at a rate of 99.8% accuracy. Humans, meanwhile? Only 33%.

This, according to John Langford, was always part of the plan. CAPTCHAs were designed as a win-win situation: Either they kept computers out, or they helped computers break some heretofore unbreakable problem. Thanks to CAPTCHAs, computers could now read distorted text.

The next development, then, was to trade text for images. A Google reCAPTCHA may ask you to identify the boundaries of a motorcycle by clicking on the squares where that motorcycle exists.

It seems that these new CAPTCHAs are both more complex and less accurate. I've run across tests that ask me to identify buses or cars in an image that has neither, and, of course, I've puzzled over whether I should click squares that have only small slices of the edge of a traffic light. I'm not alone in this feeling. Twitter is replete with internet users complaining about CAPTCHAs that are confusing or just plain wrong.

My self-imposed CAPTCHA ban stopped me from applying for a job – if they can't even trust I'm an actual human, that doesn't sound like the kind of company I'd want to work for, I told myself. It also prevented me from checking my full astrological report, which was also probably for the best. Is stubbornness rooted in my rising sign? I'll never know.

I decided I didn't need to log in to my Airbnb account after all. I dropped my desire to prepay for movie tickets. When watching a soccer game using my VPN, I was prevented from using Google search, which told me that it had "detected unusual traffic" from my IP address.

But I gave up on my self-imposed ban when I decided it was time to dig into the cheap labor that keeps spammers operating.

Despite the "low value" of email addresses and other internet functions protected by CAPTCHAs, there remains a CAPTCHA-cracking industry of unclear size. A quick Google search turns up several websites that promise cheap and quick CAPTCHA solving for meager rates. These websites – "CAPTCHA farms" – offer to solve 1,000 reCAPTCHAs for about three dollars. One thousand text CAPTCHAs, meanwhile, will cost you only one dollar.

So after weeks of refusing to do CAPTCHAs, I figured I'd break my ban and try out this "guaranteed way to have additional income in Internet [sic]," according to the company 2Captcha. Plus, if this writing stuff didn't work out, it might be nice to have a backup.

I signed up for an account on Kolotibablo, and within minutes I solved basic text-recognition CAPTCHAs. (Solving reCAPTCHAs required downloading some root-access software to my computer, the idea of which didn't thrill me.)

In total, I solved only those five CAPTCHAs in around ten minutes because of low demand for the basic CAPTCHAs I was authorized for before typing an extra "2" and getting banned. At least someone paid me a little bit to prove my humanity, I thought – even if I didn't prove it consistently or for very long. I blamed my failure on being out of practice.

But who is solving thousands of CAPTCHAs, spending hours typing numbers and identifying traffic lights for pennies? It turns out that, perhaps unsurprisingly, these companies rely on labor from some of the most economically depressed regions of the world. About a quarter of workers on the site Anti-Captcha are from Venezuela, according to data from the site itself; Indonesia, Vietnam, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Ukraine round out the top of the list. These companies say that workers make between 25 and 80 cents per hour.

These jobs allow people to work from anywhere with an internet connection, with only their smartphone or computer. And to be sure, $2 to $4 a day can stretch farther in many regions of the world than in the United States. But it is also clear that these companies care little for the workers' well-being, despite their claims that they provide easy employment for virtually anyone. I joined three Facebook groups for CAPTCHA solvers worldwide, each with thousands of members. These posts are riddled with complaints by workers that they have been banned from their platform for unclear reasons.

Most of the CAPTCHA-solving companies did not reply to my request for comment, except for Death by Captcha. The company touted its ability to solve many popular types of CAPTCHAs and the ability of people from all around the world to solve CAPTCHAs for them – "whoever wants to work can solve captchas for us" – before refusing further questions about the locations and earnings of its workers. The highest earner in the world on Kolotibablo over the past seven days, a user from Poland, had solved over 106,000 reCAPTCHAs in that time. The user earned a grand total of $110.45.

The future of CAPTCHAs may not look like the image or text questions to which we have grown so accustomed. John Langford told me that he thinks the result of a manual CAPTCHA test is probably only one of several signals that providers use to determine humanity – and maybe not a very important one.

Langford, for one, believes that the trade-off for CAPTCHAs is worth it. They're annoying, yes. And he says that he has failed a CAPTCHA, just like the rest of us. However, "To me, a CAPTCHA seems like a necessary evil," he says. "You can either pay for your accounts, or you can have some sort of barrier to complete automation. … I think it's desirable to be able to provide things to people [for free] to help them go about their day."

But with the prevalence of CAPTCHA farms, and the likelihood of machine learning's continued advancement, it is unclear how effective they remain. Maybe their primary value now is the ability to get millions of answers to questions of a company's choosing (Where is the traffic light? What does a spoon look like?) that will influence the makeup of some future AI product.

CAPTCHA farms have been around for at least a decade. But they are part of a broader trend to use poorly paid labor to solve tech problems. As we venture into a brave new world of prevalent AI, I wonder if there will be a point where technology will facilitate finding cheap labor – instead of promoting a fully autonomous future. Until then, I'll go back to doing CAPTCHAs – but just to prove my humanity.

- YouTube youtu.be