Permuted Press

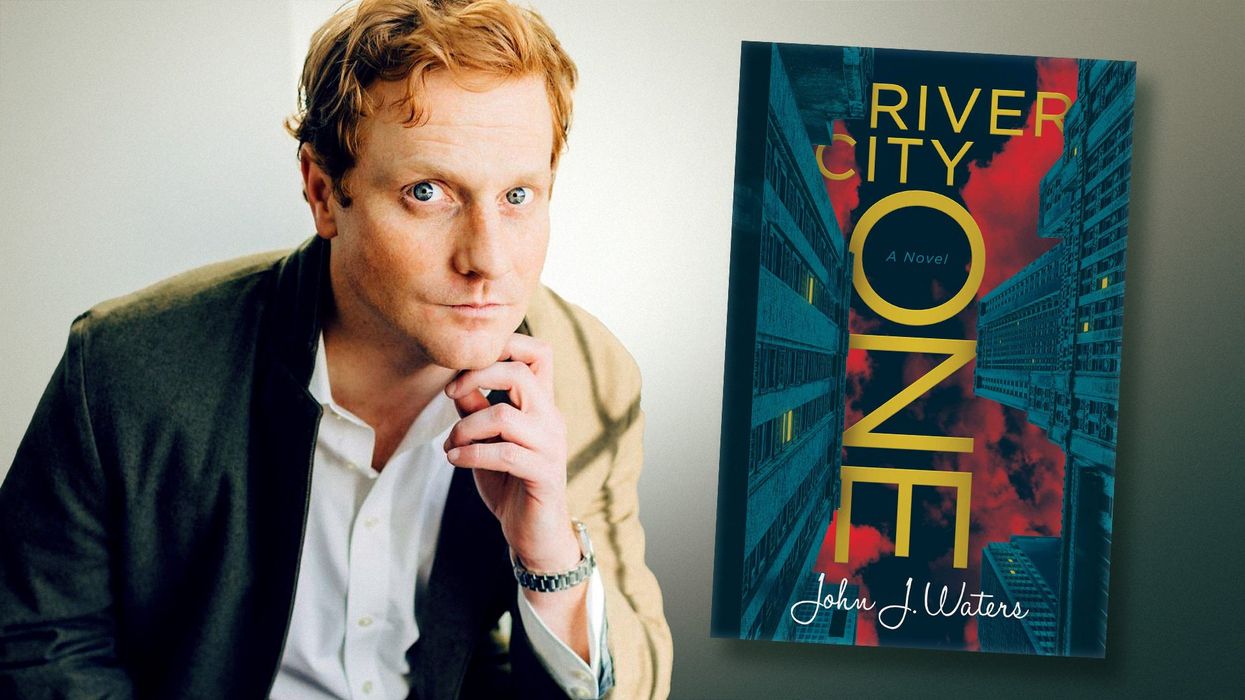

When I met John J. Waters at the Claremont Institute’s Lincoln Fellowship this summer, I was dismayed to hear him mention the impending publication of his first novel. I had nothing against the soft-spoken family man from Omaha; it’s just that years of slogging through unimaginative, MFA workshop-honed narratives purporting to teach very important lessons about race, sex, class, and the like had soured me on contemporary fiction. In fact, in 2009 I publicly resolved that I would never read a novel again.

As I spoke to Waters, however, I began to second-guess my decision. His unusual resume – graduation from the U.S. Naval Academy, six years as a Marine in Afghanistan and Iraq, law school at the University of Iowa – at least seemed to suggest he’d been working with richer material than the average first-time novelist. Also promising was the revelation that he had no formal training in fiction writing. When I learned we shared an affinity for the writing of John Cheever and other nearly forgotten masters of 20th-century fiction, I was sold.

In "River City One," Waters tackles painful questions about war, personal identity, coming home, and the banality of the everyday, while steadfastly resisting the facile answers that characterize so much of today’s fiction.

I caught up with the author to talk about learning to listen, balancing imagination and memoir, and finding escape in “realness” on the eve of the novel’s release by Simon and Schuster’s Permuted Press imprint.

Adam Ellwanger: You’re a military guy. Where were you stationed?

John Waters: In Iraq and Afghanistan, although in the military the question of where you were stationed is just the tip of the iceberg. Just as important are “Who were you with?” and “When were you there?”

I went to Afghanistan in February 2011. I was on a division staff. I worked for a general, primarily doing all-source intelligence, painting a picture of the enemy. I was giving briefings and writing things and working with the general and his staff to ensure he understood what we thought of classified reporting, detainee reports, files overlaid on Google Earth that pinpointed IED caches, enemy bed-down locations, and the like. We were synthesizing all of this information into a package or profile, something specific enough for people to use. And then, over the course of the deployment, it became very focused on finding individual people and coming up with ways to kill or capture them.

Later, I became a scout sniper platoon commander at an infantry battalion. I did that for a year, and then I was promoted to the battalion intelligence officer. In 2014, I went to Baghdad to the embassy complex and fortified the embassy during a time when ISIS was on the march. They had retaken Mosul. The black flag was flying on the technical pickup trucks running down the roads.

In hindsight, though, we were in Baghdad primarily to protect against Iranian-backed Shia militias in and around the city, filling the void left by the departure of American troops and Iraqi security forces in 2011. Then I came home and got out of the military.

You began law work after that, right?

JW: I went to the University of Iowa for law school, then went back to my hometown and became a lawyer at a firm in Omaha.

One of the things that motivated me to read your book is the fact that on paper you don't seem like a guy who would write one – someone with a background in law and the military. You also don't have an MFA, which is a plus in my book. Could you talk just a little bit about how you refined your craft if you didn't have this formal training? How did you learn to write fiction?

JW: Watching. Listening. My father's from Brooklyn and Long Island thereafter, and his family are Irish-American. They're talking people – very talkative. And when they tell stories, they tell the same stories, but they get a little different each time. They're good at embellishing and exaggerating, and usually their stories are about people and about memory. I grew up listening to them.

On the other side, my mother is from a farming town in Nebraska, four generations back: German-American people, country people. And they told stories too. Their stories were about time, it seemed: times of life, times on the farm, movements of land from one family to the next.

And so both sides of our family were obsessed with stories. That was also true of my mother in a professional sense; she was a news reporter and an editor. When someone would tell a story and she didn't like it, she would not hold back her criticism.

Then I majored in English at the Naval Academy. That’s how I found a background in storytelling and writing. I thought about an MFA when I was leaving the Marine Corps, but there are so many artists who say you have to invent your own style and your own method. I think that's true.

When did you start writing?

JW: I made a lot of lists as a kid – lists of goals. I was a guy writing lists about how I was going to defy expectations or how I was going to win something or achieve something or beat someone in tennis. I was a tennis player as a child. So, initially, writing was a place where I could name my private goals and ambitions. It wasn't a journal. It was things I wanted. Who I wanted to be came through in my writing.

Let's get into your novel. It deals with war, which haunts the book. But I wouldn’t call it a “war story.” Still, there are so many similarities between what I know about your life and what occurs in the book. Your main character is John Walker, and your name is John Waters. Like you, your main character served in the War on Terror. You set this story in Omaha. You could have set it anywhere, but you set it in your hometown.

These continuities invite readers to question the genre of your book. Is this a novel? Is it a memoir? An autobiography? How much of Walker’s story is your story?

JW: Well, it's all my story. It absolutely comes from me: what I've thought, remembered, dreamed, and observed. It comes from what I've imagined. That's me too: what I've seen and then what I've changed. Somebody asked Bob Dylan where he got all of his songs, and he said he just listened to old folk songs and then just imagined how they could be continued. That’s similar to the things I’ve written.

So it's all me. Is this a memoir? Is this autobiography? Am I recounting things that took place in my life? No. Some of it’s real, though. Omaha. Some other details, sure. But this is a work of imagination. Now, about the name John Walker – that’s true, and true life is weird. When I started at the law firm that we talked about, people said, “You're a funny guy. You know what? You're the new John Walker.” And I said “OK, I don't know who that is.” But that stuck with me for a year or more. They assigned me an office like the office in my book – the only office without windows. I opened a drawer in my desk and there was a business card in it that said “John Walker.” This man Walker had moved on from the firm, but it started this thing where it was like “OK, if I have become whatever my colleagues say I am, then am I John Waters or John Walker?”

Also, the name is restless. Walker and Waters are so similar, but they're also so different. Waters is kind of a cool name. It makes me think of the ocean. It makes me think of blue. It makes me think of things that are relaxing and calm and cool. But Walker makes me think of something anxious, restless, moving. And that's the thumbprint I wanted on this character.

Without giving too much away about the book, the name “Walker” also hints at the seminal experience from the war that sort of torments this character – walking plays a critical role there, and that's fascinating.

We have a shared appreciation for Tim O'Brien, author of "The Things They Carried," "Going After Cacciato," and a number of other “fictional” books that closely parallel the author’s real experiences in the Vietnam War. But whenever he’s been asked about the line that divides the real and the imaginary in his work, he’s been very coy. What’s your take? Does that line matter in terms of how an audience receives a book like yours?

JW: I think it's highly relevant to the quality of what's produced. It's highly relevant to a text’s capacity to capture me intellectually, emotionally, psychologically. I like O'Brien, but not because of the craft. I like O'Brien because it's so dangerous in a way. I like stories where the writer is getting so personal. I feel it's most creative. And I think that you have to be daring. Good writing demands that you be willing to destroy yourself, to obliterate a past self or expose yourself: Let it all hang out. So the line between fiction and real life is highly relevant in that regard. That sort of realness is what gets me the escape that I'm looking for in fiction.

That’s an interesting contradiction: that it's the realness that gives you the escape. Strange thing to say.

JW: I want to read something that makes me feel more alive. I want to see or hear something that makes me feel more alive. And it can happen. It's happened to me at some points – some that led to me writing this thing. And you can feel it transmit through the page when it's right.

Well, let's talk a little bit about process then. When you and I were talking back in August, one of the things that surprised me is that you wrote this book by hand. Why?

JW: I was in this battalion called 1/6, and our tagline was “1/6 hard” and all the Marines would be like, “Yeah …1/6 harder than it has to be!” In the Marine Corps, suffering was a virtue, and sometimes it’s suffering without a purpose. The hardest school renders the strongest soldier. If I was going to do this, it had to be difficult. I wanted it to be challenging. Plus, I have a job and I have to type on a computer: clack, clack, clack, clack, clack, clack, clack. You can feel it: It’s automatic, and what comes out sounds very proper and professional. It’s not the type of language that's going to move someone. So I hand-wrote it in pencil. I bought little notebooks.

I did it late at night after work, after I put my kids to bed. Handwritten pages in cursive. And once it was written through, maybe in 30 to 45 days – it didn't take too long – I went back and rewrote it in pen, reinterpreting the thing. When you have to read your own scribbles and try to figure out what you were saying, you're rethinking. That was my purpose, I suppose.

What happens after the draft in pen?

JW: Then the cleaning really begins. Once I got that nice, clean draft, then I sent it to my wonderful mother, the retired editor. But, you know, there was a moment of reticence: “She's going to see this … is this embarrassing?” But it was time to shut off the embarrassment.

There's some spicy stuff in there. As I read it, I was thinking, “Geez, I wonder if John's wife was pissed …”

JW: Yes, she’s heard it all, probably to the point where she doesn't need to read it. But yes. I exposed it to her. She gave me great edits. As I said, my mother read and ruthlessly edited the whole thing once. She refuses to go back and take a second look because she's so thorough and detailed the first time.

The whole process was probably three years in total.

You’ve talked about the exhilaration that good writing can produce. A major reason I stopped reading fiction was that it’s all become so didactic. Contemporary novels always seem to have some stupid lesson that we're supposed to learn. It became so exhausting that I just couldn't read another book that was trying to school me about oppression or injustice.

One of the things that fascinated me about your book is that it almost feels anti-didactic. It willfully resists any sort of neat resolution or any attempt to convey “a message,” whether that's pertaining to war, love, family life, or anything else. What is your sense of the theme of the book (or lack thereof)?

JW: One person under pressure. A thin line separating him from tragedy. Despair; trying to deal honestly with a world he doesn't seem to understand. That's the theme.

There is no argument. I agree. My book isn't a complaint. I'm not offering any answers. I have characters setting off, seeking to achieve something. They find themselves derailed, challenged in ways they're not prepared to navigate. That fascinates me. And of course, when we start talking about a man entering middle age with lofty ideas about how his life should unfold and finding those ideas crashing back into reality and making a mess, I'm thinking of John Cheever, John O'Hara, Richard Yates. Novelists who may be maligned today but who were popular and dominated the 1950s and ‘60s. They captured something about the American experience that persists today, even if their work isn’t so popular at the moment.

You’ve said your main character is trying to purge some trauma and put the past to bed. I suspect you hoped that writing the book would play the same function for you. So, two questions: First, is that an accurate thing to say? And secondly, if that is an accurate assessment, did you succeed in that capacity?

JW: Yes, and yes. I have a strong relationship with the past. I'm a nostalgic person by nature, whether it's for the military, or tennis, or childhood friends. I don't lose names or people. I keep hearing their voices and things they have said to me. I keep waiting for them to come back around. But as you get older, certain paths close down. Adam, you've mentioned that a part of aging is seeing options just dissolve or evaporate. That's difficult for me.

I have a very intimate relationship with my memory, and the military served a big part of that for me. I needed to get past the military — and not because I was traumatized. My experience was one of achievement, one of pride, one of accomplishment. And when that was over, I felt nostalgic for who I had been in that time and place. I needed to get beyond that. You create the thing to expiate that experience, get it out in front and look at it. Does the book serve that role for me? Yes, I feel somewhat like that. I’m over it now. It's exciting to see the book come out and to talk about it, but it's also sort of like, “What next?”

I think that we see that in John Walker, too: He seems kind of stalled, and he thirsts for a new direction that doesn't seem to present itself.

JW: I was talking just recently to a classics professor about coming home from war, and I asked, “Is it possible?”

She said, “Well, it's considered in the Homeric poems, but it's not answered.” And she went on to discuss Achilles. He has a choice, but he chooses not to go home. He chooses to fight and die in Troy. Odysseus also has an interesting journey because when he comes home and kills the suitors, he is reunited with Penelope and his son Telemachus. And many people want the story to stop there, but it doesn't. He keeps killing until Athena stops him. Why does the story end unhappily? We love happy endings, but Tennyson picked up this thread in his poem “Ulysses”: It ends by calling us “to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.” That's the nature of some people, and they have to grapple with how their nature might conflict with what they think they want to do.

So is this book a one-off for you, or is it the first of many John Waters novels?

JW: I recently talked to another Army veteran who's written about war and he was like, “Enjoy this one because it's always about the next one.” I understand what he's saying, but I don't want it to be like that. I've got to live a little bit more to have something new to say. My life doesn't move so fast that I’m “on to the next one.” I don't want to write something new unless I really have something to say. The seedling will crack the surface when it’s ready.

"River City One" is available now from booksellers everywhere.

Adam Ellwanger