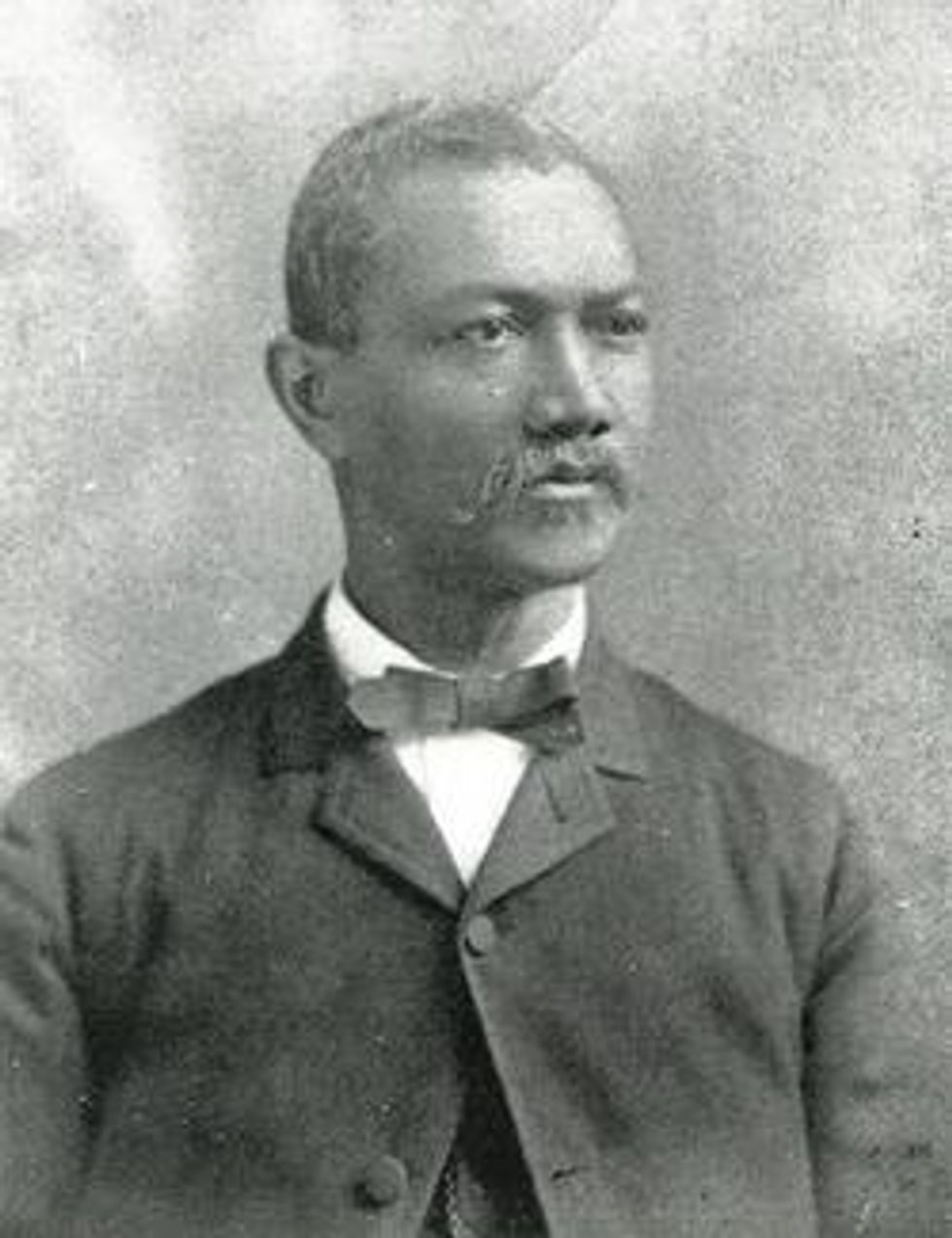

Photo Credit: African American Registry

Black History Month has once again arrived. This time of year gives us the opportunity to learn, marvel and celebrate the historic and fascinating characters within black history that, often, have had to endure incredible hardships only to make their triumphs so much greater.

Unfortunately, the cast of characters that are usually highlighted during February are a revolving door of the same people – Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, etc. While they are no less worthy than anyone of remembrance and celebration, it often makes this wonderful month far more stale than it ever should be.

There are so many incredible people that line the hallway of black history, and today I bring to you Dr. Alexander Augusta.

Dr. Augusta was born free in 1825 in Norfolk, Virginia. At that time blacks in Virginia, even free men, were forbidden, by law, to read. Despite this, he learned what he could from a local man in church named Daniel Payne and continued to learn while serving as an apprentice for a local barber.

While still a young man, he moved to Baltimore where he continued his work as a barber. His interest in knowledge and learning, begun at an early age, showed no signs of slowing down. It is unknown why he gravitated so strongly to the study of medicine, but it was here in Baltimore where that learning began under private tutors.

Hoping to formally study medicine at a university, Dr. Augusta moved to Philadelphia and applied to the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school. Whether it was simply racism or not is unknown, but the university declined his application because of “inadequate preparation.”

Though his inability to gain admission to the university would be but one of many roadblocks, he caught the eye of a professor named William Gibson who was impressed with the young man and took him under his wing. Studying in Gibson’s office, Dr. Augusta's affection for medicine was cemented and would never wane.

He returned to Baltimore and in 1847, at the age of 21, married Mary Burgoin, a woman of Native American descent. Shortly after marrying, the couple moved to California to once again pursue his dream of attending medical school. Three short years later, however, he was once again back in Philadelphia and back at square one.

In 1850, Dr. Augusta was accepted to the Medical College of the University of Toronto and by 1856 finally had his medical degree. He thrived in Toronto, being appointed the head of a city hospital, and in charge of an industrial school and setting up a successful private practice in the city.

But America, his home country, was on the verge of war, and Dr. Augusta felt a sense of duty to return and help.

[sharequote align="center"]But America was on the verge of civil war, and Dr. Augusta felt a sense of duty to return and help.[/sharequote]

The Emancipation Proclamation, taking effect the very first day of 1863, is often known as the document that freed the slaves. While this assertion is not entirely correct by itself, the document had a far more important impact upon the war – it allowed black men to enter the fight on the side of the Union Army.

Less than a week after this important change, Dr. Augusta wrote to President Abraham Lincoln and offered his services as a surgeon:

“I was compelled to leave my native country, and come to this on account of prejudices against colour, for the purpose of obtaining knowledge of my profession; and having accomplished that object … I am now prepared to practice it, and would like to be in a position where I can be of use to my race.”

The Army Medical Board, having received the letter from Lincoln, turned down Dr. Augusta’s request to serve. Undeterred by this, as usual, he traveled to Washington, D.C. and personally appealed his case in front of the board, convincing them to overturn their decision.

By April 1863, just a few months after sending his letter to the president, Dr. Augusta was the first black commissioned medical officer in the Union Army and was awarded the rank of major. He was the very first of only eight black commissioned physicians and at the time and was the highest ranking black officer in the Union Army.

Despite his abilities and his successes, he faced terrible racism during his service. Not long after his initial appointment, Dr. Augusta was brutally attacked in Baltimore while in his officer’s uniform by a group of white men. Responding to his attack, he wrote this in a local newspaper:

“My position as an officer of the United States, entitles me to wear the insignia of my office, and if I am either afraid or ashamed to wear them, anywhere, I am not fit to hold my commission.”

But it did not stop there. On another occasion, several white officers, who ranked below him and were therefore his subordinates, complained about having to serve under a black man. Dr. Augusta would later be transferred to the Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. where he became the first black hospital administrator in American history.

Before eventually leaving military service, Dr. Augusta began to fight against the segregation on trains and streetcars in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. His persistence, a theme throughout his life, would result in the eventual desegregation of trains. From a Boston newspaper, The Commonwealth, printed March 4, 1865, there is a small article on “Further Progress” that mentions his efforts:

“Surgeon Augusta of the 7th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops, (remembered as being the first colored commissioned officer in the national service, and for the brutal assault made upon him in Baltimore,) writes to the Anglo-African that he has succeeded in getting the unjust rules and practices that have existed on the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, with regard to the travel of colored passengers, between Baltimore and Washington, removed. Mrs. Augusta and a lady friend, being lately obliged to travel on that road in the smoking-car, with low-minded white persons as companions, who indulged in insulting language, he brought the matter to the attention of the president of the road, who at once gave orders that colored persons be allowed to take seats where they could find them, exactly like other passengers. It is said that there is now no difficulty, either at Baltimore or Washington, upon this point.”

After leaving military service in 1866, Dr. Augusta once again opened a private medical practice before accepting an appointment to the faculty of the medical department of Howard College. He was the first black person on the faculty of that school and the first black person in America to be on the faculty of any medical college.

Dr. Augusta’s life was filled with trials, triumphs and many firsts for black people in America. Even in death he would continue that legacy. After a long and storied career and life, Dr. Augusta died in 1890 in Washington D.C. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery receiving full military honors – the first black officer to be accorded this honor.

For other articles and writings by Darrell, please visit the Milk Crate.

–

TheBlaze contributor channel supports an open discourse on a range of views. The opinions expressed in this channel are solely those of each individual author.