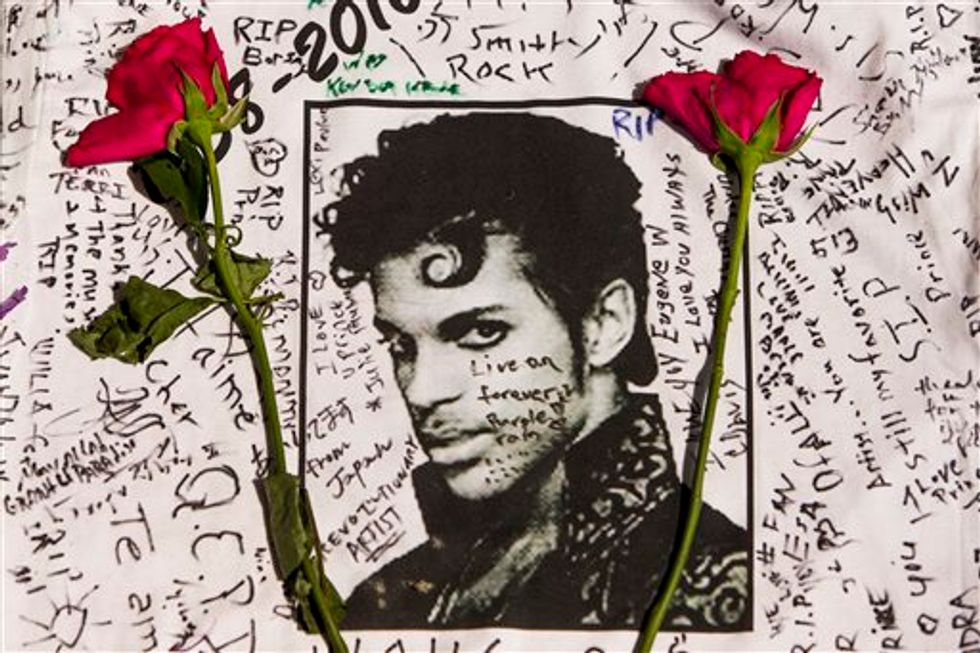

Prince performs onstage at the 36th Annual NAACP Image Awards at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles in March 2005. (Photo by Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

The death of yet another rock icon, Prince, has left in its wake familiar scenes of gatherings of saddened fans, cover tributes, buildings illuminated in purple and, of course, a social media tornado. I've noticed with Prince and others, along with the accolades and fond memories, the contrarians come out to play as well.

The populist meme seems to be that, yes, these were talented people, but the outpouring of emotion is misplaced and misguided. They were no better than the rest of us, nor were they particularly good people, thus unworthy of such praise.

Here are a few comments I've read recently about Prince:

“Look I get we all sang a song in a car or danced at a party to a Prince song. But running his movie for 4 days and changing the colors of buildings to purple. CAN WE ALL GET A FREAKING GRIP HERE! How about the single moms who raise 3 kids or the Dad who works 2 jobs to pay his bills. Or the kid who studies his ass off to get 80's! Where's their color on buildings?”

Another offers:

“When did movie stars, athletes and musician become the moral compass of our society? Yes prince was a great talent. Anyone want to review his record of treating women. Country is doomed.”

There are kernels of truth in both of these observations. But my question is this: Should we not mourn the death of extraordinary artists because they also happened to live imperfect lives? To the first line of reasoning, I ask this: Because other people struggle can we not remember those whose works actually affected us personally - be it a song a we love, a memory we share, or just an iconic symbol of an era we remember fondly? Such a mentality does not exalt the masses, it just serves to diminish the truly great. People one hundred years from now will still be celebrating Prince's music and they will not remember most of the other five billion people who inhabited the globe in more mundane anonymity at the same time.

As to the second objection, there is an expression in the military: You salute the rank, not the man. The same is true in memorializing the truly gifted who have passed. Besides, the celebration of great artists upon their deaths, regardless of their personal flaws, is nothing new.

Few of Beethoven’s contemporaries would describe him as a very nice guy. He scorned the society in which he moved, had a brusque, arrogant way about him, was often unkempt and disheveled, and purposefully arrived late for invitations just to show he could. He tried to have his own brother arrested for living with a woman out-of-wedlock (different times then). After another brother’s death he sued his sister-in-law for custody of her son, Karl, his godson, and then went on to be such an overbearing master that he drove the boy to a suicide attempt. Young Karl finally fled and joined the Austrian army.

Yet, in 1827, when the great composer died, throngs came out to mourn his passing. Many thousands of citizens lined the streets of Vienna for the funeral procession. Estimates vary, but witnesses reported anywhere from 10,000 to 30,000 onlookers. Theaters were closed, and many notable artists participated in the funeral procession as pallbearers or torchbearers. They came to mourn the music, the achivements, not the man per se.

Certainly this tribute should not have been ridiculed, as the contrarians above might have if alive then, just because there were hard-working smiths and laborers and shop-keepers also alive at the same time whose funerals attracted far fewer mourners and yet who, in many ways, led more honorable, if also less notable, lives. I have Beethoven’s works - 189 years after his death - still gloriously pumping out of my iPod. Indeed, the Beethovens of the world will live on forever, far after I am gone and forgotten, because of their contributions to the story of us as artists, not as noble exemplars of human decency.

Today the world would be so much emptier without the music of so many musicians we have lost in the past twelve months as if some angry god has cast a plague on the pop culture of my youth - B.B. King, Glenn Fry, David Bowie, Scott Wieland, Merle Haggard, and Prince. But I cannot say I know enough about these men’s lives to place them on an altar for my children to look to, beyond their music.

We can and should separate the art from the artist. Consider John Lennon. Here was a man who, with a straight face, challenged us to “imagine no possessions, I wonder if you can…” Give me a break. When he died 1980, Lennon's net worth was $150 million, including five apartments in the tony Upper West Side Dakota co-op; three units he kept just for storage - presumably for all the possessions the rest of us shouldn’t imagine. But still, this glaring hypocrisy doesn’t diminish the pleasure I get from listening to “Dear Prudence,” “In My Life,” “Come Together,” “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away,” “Norwegian Wood,” "A Day in The Life," "Lucy In The Sky...," Etc. (I never liked “Strawberry Fields,” sorry).

So, when artists whose work you love pass, it’s perfectly okay to feel a loss of their craft and mourn the music we will never hear by those no longer around to compose just one more song. One can only wonder had Mozart died at 66 and not 36 how much added beauty there would be in the world today (Beethoven’s greatest work, the 9th Symphony, wasn’t performed until he was in his 50's). Such an end to a story is worthy of sadness, even if others live nobler personal lives.

Brad Schaeffer is an energy broker, columnist, historian and author of the World War II novel "Hummel's Cross" about a Luftwaffe flying ace who saves a family of Jews during the height of the air war over Europe. Drop him a note at: shafemans@yahoo.com.

–

TheBlaze contributor channel supports an open discourse on a range of views. The opinions expressed in this channel are solely those of each individual author.