© 2025 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Witchcraft & the Occult Are Seen as Deadly 'Plagues' In 3rd World Countries -- Here's Why

April 25, 2012

"There are also those who believe that possession of some organs of infants and albinos can turn them rich."

This is a crosspost from Beliefnet.com.

A fear of witchcraft? In our enlightened age?

According to Reuters, the British news agency, a woman from the island of Sri Lanka off the southern tip of India has been charged with casting a spell on a 13-year-old Saudi girl during her family’s trip to a shopping mall.

In Zimbabwe, local leader Maliki Masuku fined Shadreck Dube for performing witchcraft and “terrorizing nurses at Nathisa Clinic” in Mapoto.

Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete in a New Year address to the nation ordered a crackdown on what he said was a growing number of murders and child rapes linked to witchcraft.

In Cornwall, England, the local council is defending its decision to include teaching children about witchcraft in religious education lessons. The Cornwall Council says that from the age of five, children should begin learning about pagan sites like Stonehenge and at the age of 11, pupils can begin exploring “modern paganism and its importance for many in Cornwall.” Critics say the council is offering “witchcraft lessons.”

Witchcraft? Seriously? The United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund – UNICEF – says that tens of thousands of children in Africa each year are tortured and killed because of witchcraft. Blame is divided between local witchdoctors and Pentecostal churches that have led opposition to the witchdoctors.

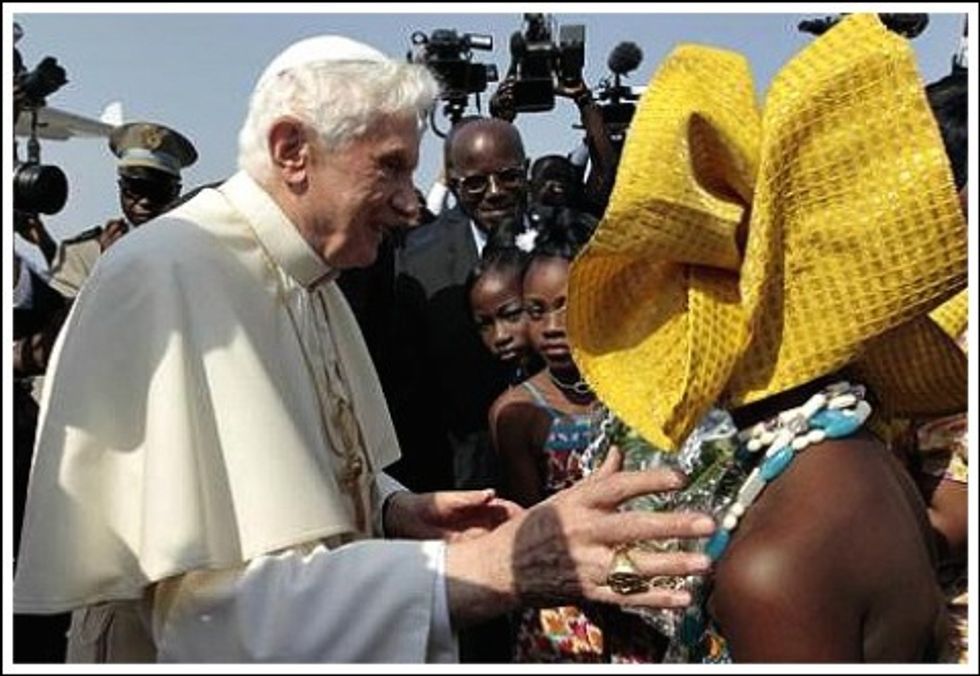

In his recent visit to Africa, Pope Benedict XVI called witchcraft a “plague.” Africa’s bishops in 2009 denounced witchcraft as a “social drama” – where in poor households or those affected by catastrophes culprits are tortured or killed – blamed for the catastrophe.

Islam takes witchcraft very seriously – and bans it. Particularly forbidden is having anything to do with jinni – evil spirits – “genies,” which are prominent in local folklore. If convicted in Saudi Arabia, a witch or sorcerer or anyone consorting with a jinn is put to death. The Saudis have no written criminal code. Court rulings are based on individual judges’ interpretation of shari’ah – Islamic religious law.

“The punishment is always beheading for anyone found guilty of witchcraft,” Saudi lawyer Waleed Abu al-Khair, a human rights activist, told Reuters. Last December, Amnesty International condemned the beheading of Amina bint Abdulhalim Nassar, who was arrested in the Saudi city of Qurayat on charges of “witchcraft and sorcery.” The Arabic-language Al Hayat newspaper reported that that while searching the woman’s home, authorities found a book on witchcraft, women’s veils and bottles of “an unknown liquid used for sorcery.” According to the charges, she claimed to be a healer and would sell three bottles of the liquid for 1500 riyals – about $400.

In September, Abdul Hamid Bin Hussain Bin Moustafa al-Fakki, a Sudanese national, was beheaded in Medina after being convicted of casting a spell involving jinni designed to reconcile a divorced couple.

“Saudi law does not clearly outlaw sorcery,” reports Cecily Hilleary of Middle East Voices, a Voice of America website, “but the country’s legal system is based on a strict interpretation of Islamic law.”

According to the Understanding Islam website, belief in magic is integral to the Islamic tradition. Many Saudis say their belief in sorcery and jinni is an integral part of Islam.

Anyone Muslim denies their existence is not a true believer, according to Christoph Wilcke, Senior Researcher for the Middle East and North Africa Division at Human Rights Watch.

“I recall a meeting with the highest adviser to the Minister of Justice in Saudi Arabia a few years ago,” Wilcke told the Middle East Voices, a Voice of America website. “I asked him, ‘How do you prove sorcery or witchcraft in court?’ And the answer he gave me, after looking a little bit stupefied, was to point to the American justice system – how do Americans know what is pornography?

“He basically said, ‘I know it when I see it.’”

Witchcraft is a profitable business in Saudi Arabia and throughout the Muslim world, he said.

“The poor, the ailing and the heartsick, believing in magic, turn to fortune tellers and herbalists for help,” writes Hilleary.

In the west, witchcraft is trivialized with children’s books such as Harry Potter and Disney movies and TV shows that present it as harmless.

However, the Vatican has called on African authorities to ban sorcery with rigid laws. When receiving visiting bishops from Angola, the Pope Benedict XVI declared that a “joint effort” of the church, civil society and governments must be made “to counter the “scourge” of ritual “murder of children and the elderly” due to witchcraft. Denouncing it, he urged officials to educate church members against “practices that are incompatible” with Christianity.

He recommended “a joint effort of the ecclesial community” which would “counter this calamity, trying to determine the deep meanings of these practices, to identify the risks for pastoral and social development, and to find a method leading to its definitive eradication, with the cooperation of governments and civil society.”

“The UNICEF study,” writes Kofi Akosah-Sarpong on the website GhanaWeb, “shows that gradually the international community is getting grip of the implications of witchcraft and other inhibitive beliefs in Africa’s development.

“In Ghana, prominent figures such as ex-President Jerry Rawlings are questioning certain inhibitive cultural practices that not only dehumanize Ghanaians and Africans but also undercut their progress. On a recent visit to Africa, Roman Catholic Pope Benedict XVI strongly spoke against the dangers of witchcraft beliefs and other inhibitive cultural rites that have been entangling Africans’ progress,” writes Akosah-Sarpong.

“Whether in Rawlings or Pope Benedict XVI, mixture of the international and the African campaigns are doing the work, helping to raise not only awareness and throwing light into the dark recess of the African culture but also how to tackle the dangers.”

In the Zimbabwe case, Chief Masuku fined Village Head Dube after a traditional healer, or inyanga, often described by the politically incorrect term of “witchdoctor,” accused him of owning goblins that were disturbing the nurses at the local clinic. The staff had complained of nightly sexual harassment by the supernatural creatures, sources said.

Chief Masuku called in the spiritual man to do a cleansing ceremony at the clinic. The witchdoctor declared that the goblins belonged to Dube. Tampers flared, resulting in Dube’s arrest together with six members of his family. They were charged with undermining the chief’s authority. A family spokesman, Anele Dube told the Voice of America they were released after prosecutors in the town of Kezi said they were still assessing evidence.

“We did not do anything that disrespected the court of the chief,” the spokesman said, adding that “the witchcraft accusations against my uncle are simply false.”

Under Zimbabwe’s Witchcraft Suppression Act, engaging in witchcraft practices is a criminal offense punishable by a fine or up to five years in jail.

Chapter V of the law reads: “Any person who engages in any practice knowing that it is commonly associated with witchcraft, shall be guilty of engaging in a practice commonly associated with witchcraft if having the intention to cause harm to any person.”

In 2008, Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete used his New Year address to the nation to call for a crackdown on witchcraft responsible for a rash of murder and child rapes.

He blamed witchcraft practitioners for “stupid beliefs that having sexual intercourse with infants can bring them fortune,” he said. “There are also those who believe that possession of some organs of infants and albinos can turn them rich.”

He has ordered police to come down hard out on such practices. According to Kikwete, albinos were being targeted by some witchdoctors and that police reported several cases of people exhuming the freshly-buried bodies of infants to remove organs to make potions.

Witchcraft cases are increasingly in the news in Muslim nations. In April 2010, the New York Times reported on the case of Ali Hussain Sibat, a Lebanese television astrologer who hosted a psychic call-in show on Arab television.

In May 2008, he traveled to Saudi Arabia to perform a religious pilgrimage to Mecca. Religious police arrested him on charges of sorcery. Sibat was condemned to death and his execution was scheduled for April, 2010. However, pressure by human rights groups and the high profile of his case led the Saudi government to stay his execution. Last October, Saudi government officials were reported as saying that while his execution had not taken place, Sibat is still in prison.

Regarding the more recent case in which the Sri Lankan woman was accused of casting a spell on a Saudi family at a shopping mall, police spokesman Mesfir al-Juayed confirmed to Reuters by phone that details of the woman’s arrest published in local media were correct.

The daily Okaz newspaper reported that a Saudi man had complained his daughter had “suddenly started acting in an abnormal way, and that happened after she came close to the Sri Lankan woman” in a large shopping mall in the Saudi city of Jeddah. “He reported her to the security forces, asking for her arrest and the specialized units dealt with the situation swiftly and succeeded in arresting her,” Okaz reported.

Britain’s Impact magazine describes a case in which a 15-year-old London boy, Kristy Babu, died during an exorcism performed by his sister Magalie Bamu, 29, and her boyfriend Eric Bikubi, 28. All are originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“A horrifically violent exorcism, involving a hammer, chisel, knives and metal bars, left Kristy begging to die,” reports Ellis Schindler for Impact. “Kristy was staying with the couple in London, along with his other siblings, for Christmas. Bikubi accused them of bringing witchcraft or kindoki into the house. Two of Kristy’s siblings were also subjected to torture but Kristy became the main focus of attention after wetting himself.

“The wasn’t the first time the couple has accused someone of being a witch. In 2008 Bikubi accused one of their house guests of being a witch after he caught her biting her nails. The girl was then subjected to three foodless, sleepless days of praying with the couple to release the kindoki as well as having her long hair cut short to release the spirits.”

In 2005, Sita Kisanga was found guilty of torturing an eight-year-old in London, believing the girl to have kindoki. She told the court that, “Kindoki is something you have to be scared of because in our culture kindoki can kill and destroy your life completely.”

But officials in Cornwall, England, say there’s nothing to fear. That worries Cristina Odone writing in the Daily Telegraph.

“Saint Morwenna, who in the sixth century built a church on a cliff with her bare hands, must be turning in her grave,” observes Odone. “Her beloved Cornwall, the last redoubt of Celtic Christians, is to teach witchcraft and Druidry as part of religious education.”

It seems that the politically correct Cornwall Council regards Christianity as no better than any other superstition.

“Fear of being judgmental is so ingrained today that no one dares distinguish between occult and Christian values, the tarot and the Torah, the animist and the imam,” writes Odone.

“Right and wrong present a problem for liberals who spy covert imperialism or racism in every moral judgment. Saying someone has sinned is ‘disrespecting’ them, as Catherine Tate’s Lauren Cooper might say.

“Speaking of religious values is as dangerous as playing with the pin on a hand-grenade: it could end up with too many Britons blown out of their complacency. No one should dare proclaim that adultery is wrong; greed, bad; or self-sacrifice, good. In doing so, they’d be trampling the rights of those who don’t hold such values.

"This mentality is not confined to Cornwall.

“When the BBC’s ‘The Big Questions’ asked me to join its panel of religious commentators two years ago, I was taken aback to find it included a Druid. Emma Restall Orr rabbited on inoffensively about mother nature, but I was shocked that her platitudes were given the status of religious belief by the program makers.

“Restall Orr exults in her website that the media has stopped seeing Druidism ‘as a game’ and now invites her on serious faith and ethics programs from ITV’s ‘Ultimate Questions’ to Radio 4’s ‘The Moral Maze’ and ‘Sunday Program.’

“In pockets of Cornwall, children will point out a nun in her habit: ‘Look, a Druid!’ Their parents will merely shrug,” writes Odone, “one set of belief is as good as another. How long before the end of term is marked by a Black Mass, with only health and safety preventing a human sacrifice?”

Article courtesy of Beliefnet.com, the distinct online resource for inspiration and spirituality where you’ll find thousands of inspiring features, uplifting stories and access to other great resources.

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

more stories

Sign up for the Blaze newsletter

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.

Related Content

© 2025 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.