New Video Game Invites Players to Experience the Joys and Struggles of a Real-Life Family Battling Cancer

The absence of any real control is meant to allow players to experience the real feelings of joy, hope, helplessness and despair.

It’s nothing like what you typically think of when you hear someone mention a “video game.”

Games are fun, strategic and fast-paced. They offer players the chance to exercise some degree of control, while also offering a brief escape from reality.

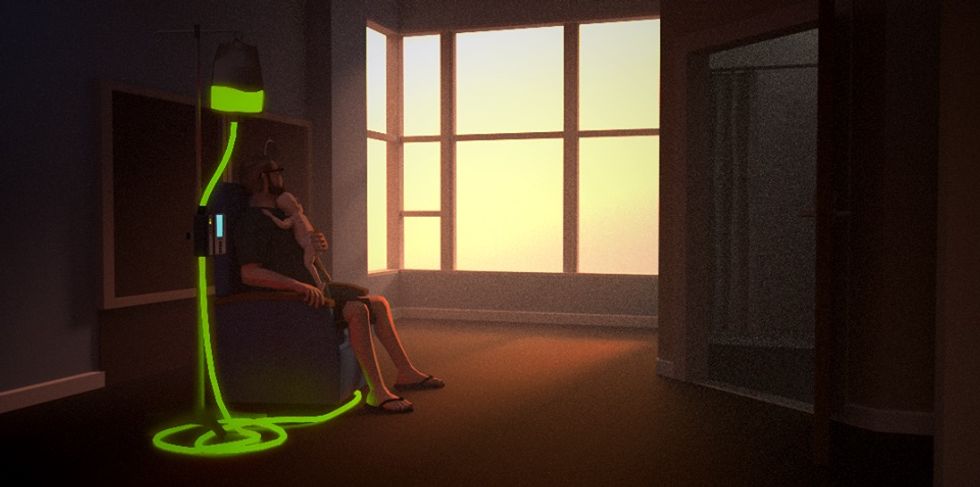

"That Dragon, Cancer" is not your average video game.

Ryan and Amy Green made the game as a tribute to the life of their late son, Joel, who passed away when he was just five years old.

The game is a memoir that invites players into the intimate moments of the Greens’ family life. It’s more like an interactive visual story book than most video games currently on the market.

The Greens, who live in Colorado, spent three years developing the game with a small team of artists and designers.

Ryan, who is a programmer, quit his job to work on the project.

“I feel like 'That Dragon, Cancer' is one of those breakthrough moments,” New School professor and author John Sharp told the New York Times. Sharp is a professor of games at the New School and the author of “Works of Game,” a book about pairing of games and art. “I think we may look back at this game and see this as a touch point, a moment of rethinking what people can do with interactivity.”

"That Dragon, Cancer" includes audio from home movies and from “Thank You for Playing,” a film about the Greens that premiered last year at the Tribeca Film Festival.

The game is an animated, artful depiction of the Greens’ emotional state during their son’s bout with cancer. When the doctor announces there are no more treatments for Joel’s cancer, water fills the room.

There is a dragon, but the game predominately consists of everyday moments like phone calls and hospital visits. Players hear Joel’s laughter, which occurs often, but they also listen to the prayers of parents, who are Christians, shouted on the last night of their son’s life.

The controls are intentionally limited. One scene involves a go-kart race through a hospital, but the speed of the go-kart is set by the game. This frustrated some critics, but according to Ryan, “That’s the point.”

“All you can do is steer, hopefully,” he told the Times.

The absence of any real control is meant to allow players to experience the real feelings of joy, hope, helplessness and despair, just as the Greens did with Joel.

“One of the great strengths of video games is that automatically a player goes into a game expecting to have some agency,” Amy told the Times. “And it felt like the perfect way to talk about cancer, because all a parent wants is to have some agency.”

So why provide players any control at all? In other words, what’s the point of making it a video game?

Sharp made a comparison between the current cultural status of games to that of painting during the Italian Renaissance, when art was beginning to shift from being functional to something valued simply for its aesthetic.

“It took hundreds of years to make this transition for painting,” he said. “So, looking at it through my art-historian goggles, it’s not really a surprise that there are folks who are outside the epicenter of the games community who make the assumption that if games aren’t escapist, they must be educational or therapeutic.”

Despite the attention "That Dragon, Cancer" has received — from podcasts, to magazine articles, to a documentary film — the game’s sales in its first month reflect just how different it is from mainstream varieties like "Grand Theft Auto V," which about 4 million people own on Steam, the main digital storefront for PC games, according to SteamSpy.

Some 10,000 people have bought the Greens’ game since it launched last month, a modest number when one considers the three years it took to develop and the eight-person team who worked to create it.

“I always tell people, ‘You know those indie, artsy films that Ryan likes and no one else likes?’” Amy said. “‘There are video games like that.’”

Watch the game trailer:

(H/T: New York Times)