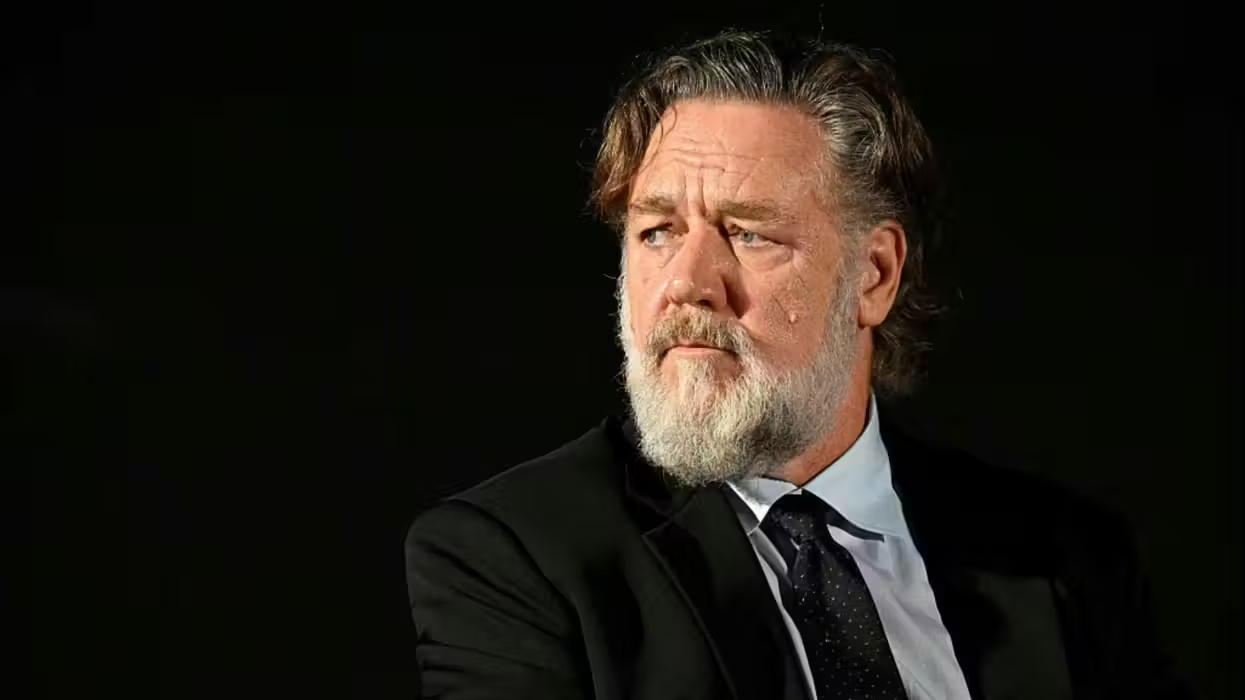

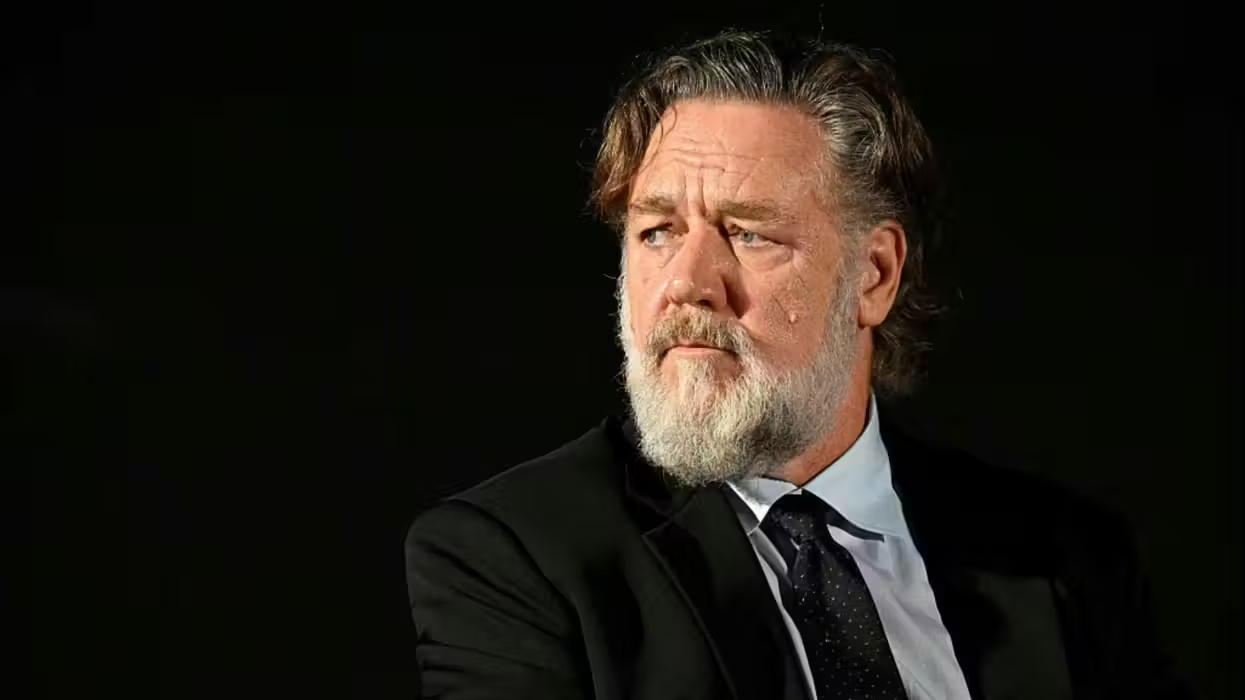

Michael Kovac/Getty Images

The star’s fearless turn as the infamous Hermann Goering marks a return to form

Say what you will about Russell Crowe, but he has never been a run-of-the-mill actor.

At his best, he surrenders to the role. This is an artist capable of channeling the full range of human contradictions. From the haunted integrity of "The Insider" to the brute nobility of "Gladiator," Crowe once seemed to contain both sinner and saint, pugilist and philosopher.

In a time when truly commanding leading men are all but extinct, Crowe remains — carrying the weight, the wit, and the weathered grace of a bygone breed.

Then, sometime after "A Beautiful Mind," the light dimmed. The roles got smaller, the scandals bigger.

There were still flashes of brilliance — "American Gangster" with Denzel Washington, "The Nice Guys" with Ryan Gosling — proof that Crowe could still command attention when the script was worth it. But for every film that landed, two missed the mark: clumsy thrillers, lazy comedies, and a string of forgettable parts that left him without anchor or aim. His career drifted between prestige and paycheck, part self-sabotage, part Hollywood forgetting its own.

But now the grizzled sexagenarian returns with "Nuremberg" — not as a comeback cliché, but as a reminder that the finest actors are explorers of the human abyss. And Crowe, to his credit, has never been afraid to go deep.

In James Vanderbilt’s new film, the combative Kiwi plays Hermann Goering, the Nazi Reichsmarschall standing trial for his part in history’s darkest chapter. The movie centers on Goering’s psychological chess match with U.S. Army psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who becomes both fascinated and repulsed by the man before him. Goering, with his vanity, intelligence, and theatrical self-pity, is a criminal rehearsing for immortality.

The film unfolds as a dark study of guilt and self-deception. Kelley, played with that familiar, hollow-eyed tension of Rami Malek, sets out to dissect the anatomy of evil through Goering’s mind. Yet the deeper he digs, the more he feels the ground give way beneath him — the line between witness and accomplice blurring with every exchange.

Crowe’s Goering is not the slobbering villain of old war films. He’s disturbingly human, even likeable. He jokes, he reasons, he charms. He’s a man who knows how to disarm his enemy by appearing civil — and therein lies the horror. It’s a performance steeped in Hannah Arendt’s famous concept of the “banality of evil”: the idea that great atrocities are rarely committed by psychopathic monsters but by ordinary people made monstrous — individuals who justify cruelty through bureaucracy, obedience, or ideology.

Arendt wrote those words after watching Adolf Eichmann, another Nazi functionary, defend his role in the Holocaust. She was struck not by his madness but his mildness — his desire to be seen as merely following orders. Crowe’s Goering embodies that same terrifying normalcy. He doesn’t see himself as a villain at all, but as a patriot — wronged, misunderstood, and unfairly judged. It’s his charm, not his cruelty, that unsettles.

The brilliance of Crowe’s performance is that he resists caricature. He reminds us that evil doesn’t always wear jackboots. Sometimes it smiles, smokes, and quotes Shakespeare. It’s the kind of role only a mature actor can pull off — one who has met his own demons and understands that evil seldom announces itself.

It is also, perhaps, the perfect role for a man who has spent decades wrestling with his own legend. Crowe was once Hollywood’s golden boy — rugged, brooding, every inch the leading man — but the climb was steep and the fall steeper. Fame, like empire, demands endless victories, and Crowe, ever restless, grew weary of the war.

RELATED: Father-Son Movie Bucket List

With "Nuremberg," he hasn’t returned to chase stardom but to confront something larger — the unease that hides beneath every civilized surface. Goering, after all, was no brute. He was cultured, eloquent, even magnetic — proof that wisdom offers no wall against wickedness. And in a time when truly commanding leading men are all but extinct, Crowe remains — carrying the weight, the wit, and the weathered grace of a bygone breed.

At one point in the film, Goering throws America’s own hypocrisies back at Kelley: the atomic bomb, the internment of Japanese-Americans, the collective punishment of nations. It’s a rhetorical trick, but it lands. Crowe delivers those lines with the oily confidence of a man who knows that moral purity is a myth and that self-righteousness is often evil’s most convenient disguise.

The film may not be perfect. Its pacing lags at times, and its historical framing flirts with melodrama. But Crowe’s performance cuts through the pretense like a scalpel. There’s even a dark humor in how he toys with his captors — the court jester of genocide, smirking as the world tries to comprehend him.

Crowe’s Goering is, in the end, a mirror. Not just for the psychiatrist across the table, but for us all. The machinery of horror is rarely built by fanatics, but by functionaries convinced they’re simply doing their jobs.

Crowe’s performance reminds us why acting, when done with conviction, can still rattle the soul. His Goering is maddening and mesmeric. He captures the human talent for self-delusion, the ease with which conscience can be out-argued by ambition or fear. "Nuremberg" refuses to let the audience look away. It reminds us that every civilization carries the seed of its own undoing and every human heart holds a shadow it would rather not confront.

Russell Crowe is back, tipped for another Oscar — and in an age when Hollywood produces so few films worthy of our time or our money, I, for one, hope he gets it.

John Mac Ghlionn

Contributor