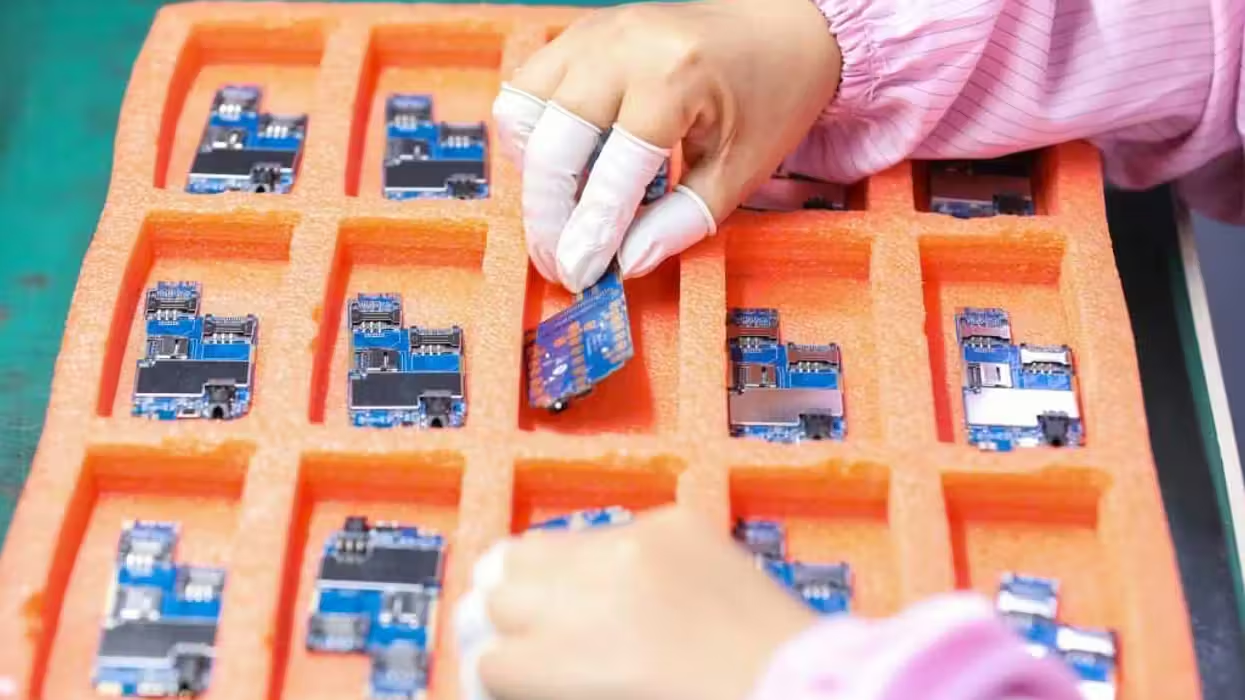

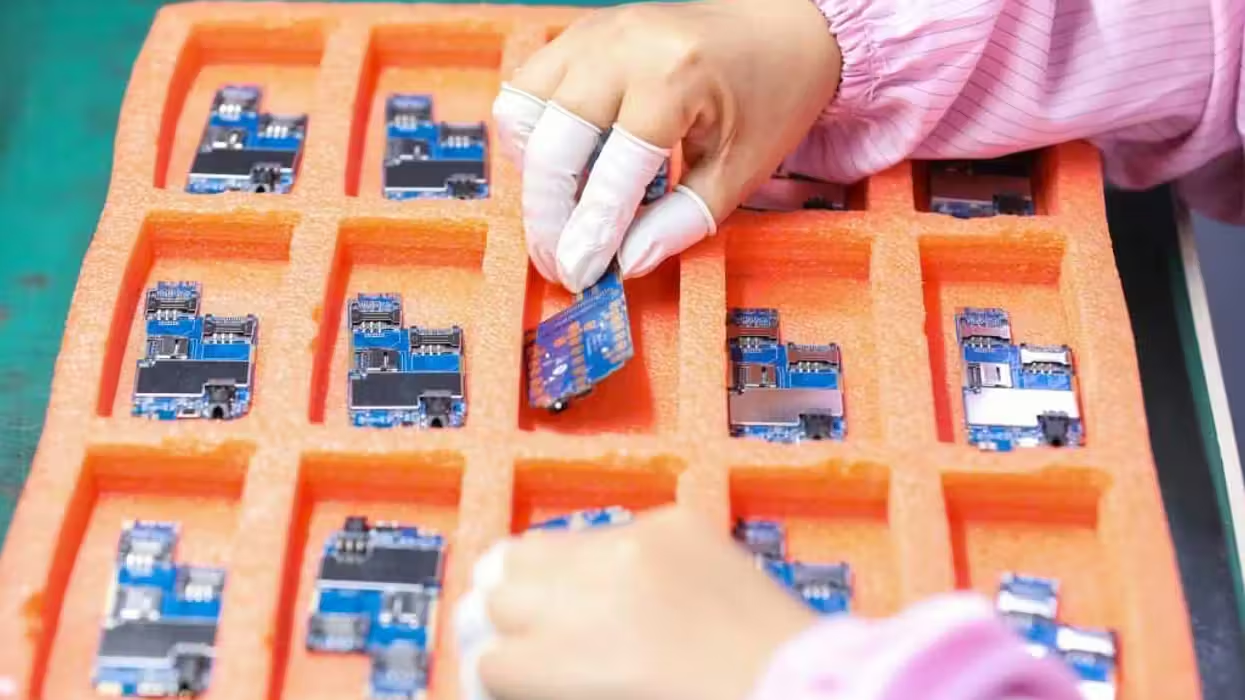

Photo by Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Beijing's computer chip Manhattan Project is just the beginning.

To invoke the “Manhattan Project” is to summon a particular ghost: one of total mobilization, of scientists sequestered in secret rooms, of a national destiny forged in the heat of a singular, technological breakthrough by a threatened country. In the 1940s, the location was Los Alamos; in 2026, it is a secure laboratory in Shenzhen. Here, the objective is not a nuclear chain reaction, but the etching of light onto silicon at a scale so small it defies the physical properties of the air we breathe.

The technology is extreme ultraviolet lithography. To the uninitiated, it is a manufacturing process; to the Chinese state, it is the choke point that must be cleared if the nation is to thrive. For years, Washington operated under the assumption that the complexity of these machines — monstrous contraptions the size of city buses, requiring the synchronization of molten tin droplets ionized by lasers 50,000 times a second — would remain a Western monopoly, a “Silicon Shield” guarded by the Dutch firm ASML. That assumption, like so many others in this decade, has proved precarious.

If China succeeds, it will have neutralized the West’s major lever.

The machinery of this mobilization is vast. At the top sits the Central Science and Technology Commission, directed by Ding Xuexiang, a man whose proximity to President Xi Jinping signals that the semiconductor is no longer a matter of commerce, but of national interest. The strategy is one of “brute-force innovation.” In this world, the tech giant Huawei coordinates a web of institutes and thousands of engineers, a private entity acting as a limb of the state.

There is an urgency in the way the talent was gathered. Since 2019, Beijing has been luring Chinese-born engineers back from foreign firms with signing bonuses of $700,000 and the promise of a place in history. When they arrive, they disappear. To protect the project’s secrecy, these returnees work under false identities, wearing fake ID badges and using aliases even among their colleagues. They operate with military-like discipline; scientists sleep on-site at laboratories, barred from returning home during the work week, their phone access restricted as if they were handling the codes to a nuclear missile silo.

One thinks of the “Two Bombs, One Satellite” program of the 1960s, the earlier state-directed campaign that yielded China’s first atomic and hydrogen bombs. The rhetoric is the same: the patriotic return of the diaspora, the vanquishing of foreign embargoes through indigenous innovation. The narrative is of national rejuvenation, of overcoming “past humiliations” by proving that the mind cannot be embargoed. In early 2025, the prototype emerged. It is, by all accounts, crude and enormous, filling nearly an entire factory floor in Shenzhen, a stark contrast to the refined, bus-sized machines of the West. However, it is operational, generating the 13.5 nm ultraviolet light beam necessary to etch circuits at the 5 nm scale and below.

RELATED: Chinese elites paying American surrogates to breed 'mega-families'

The technical challenge of EUV is a kind of high-stakes alchemy. Because 13.5 nm light is absorbed by glass and even air, it must travel in a vacuum and be focused by specialized multilayered mirrors with atomic-level precision. To achieve this without the help of Western suppliers such as Germany’s Zeiss, the Chinese relied on obsessive, focused resourcefulness. They scoured secondary markets for old equipment; they salvaged components from older ASML machines; they acquired restricted parts from Japanese firms Nikon and Canon via intermediaries.

Perhaps most revealing is the “SWAT team” of 100 young engineers assigned to take these machines apart and put them back together. Each desk is monitored by a camera as they meticulously reverse-engineer components, a process of “training through deconstruction.” The scene is of Ph.D.s poring over discarded machinery like puzzle pieces, striving to unlock the nuances of a technology they were never meant to have. The result is a proof of concept that observers had believed was a great many years away.

We are witnessing the early phase of a race for AI chips. If the 20th century was defined by oil reserves and nuclear arsenals, the 21st will be defined by computing power and silicon fabs. The U.S. has responded with the CHIPS and Science Act, investing over $50 billion to reshore production, while simultaneously attempting to choke off China’s access to the most advanced tools.

Yet there is a quandary in this decoupling. The semiconductor supply chain is global and interdependent. An ASML machine is a mosaic of components from Japan, Germany, and the U.S. By forcing China toward self-sufficiency, the West may be inadvertently creating the very monster it fears: a China capable of producing advanced chips on entirely China-made machines, “kicking the United States 100% out of its supply chains.” The goal is a “digital Iron Curtain,” where two separate technological stacks, one Chinese-led, one Western-led, operate in parallel, neither reliant on the other’s hardware or software.

For now, the project remains a work in progress. Mass-producing 2-5 nm chips in China is likely still years away, perhaps 2030 or beyond. The machines must be refined; the optical mirrors remain a weak point. Yet the significance of the prototype is not its current efficiency, but its existence, which demonstrates an irreversible commitment to Chinese technological independence.

The air in Shenzhen is thick with techno-optimism and a quiet, state-sanctioned fervor. When a Chinese chip startup recently went public, its stock soared 693%, a sign of a public that views each new milestone as a victory against a foreign blockade. This is the intersection of technology and national pride. If China succeeds, it will have neutralized the West’s major lever. If it fails, the U.S. may extend its lead. The breakthroughs, however, feel inevitable to those inside the project. They are playing a long game, one where the cost — in billions of dollars, in the isolation of their brightest minds, in the fracturing of the global order — is simply the price of admission.

Stephen Pimentel