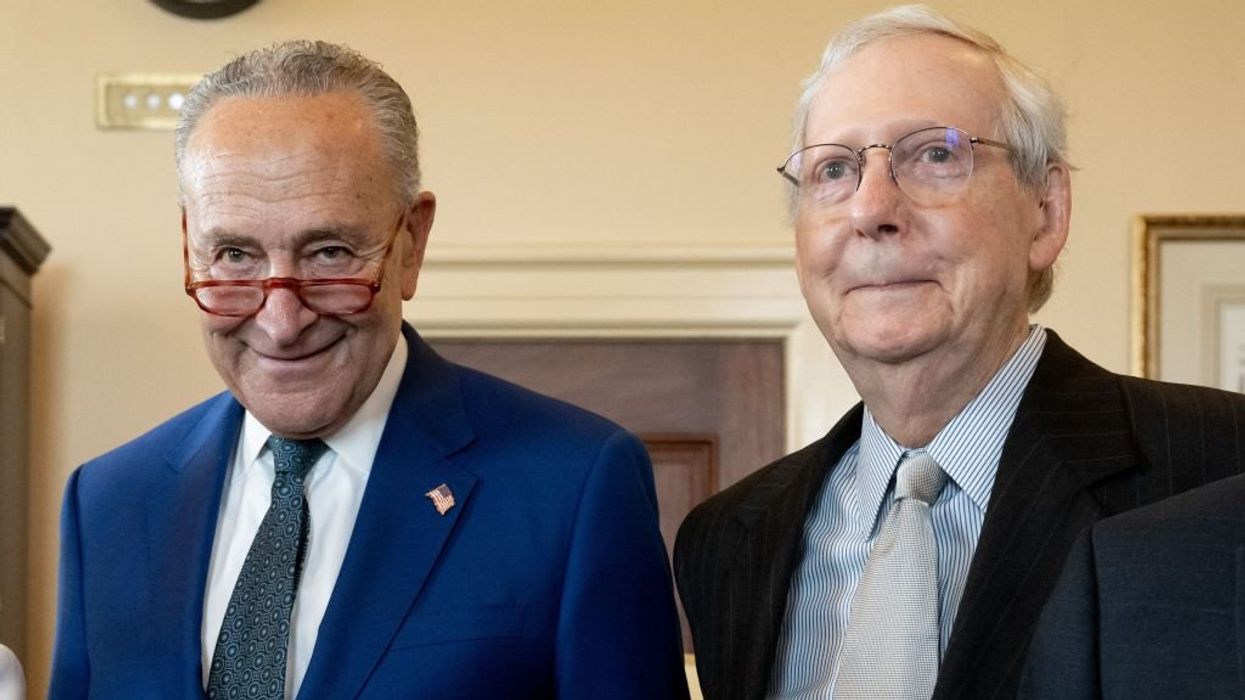

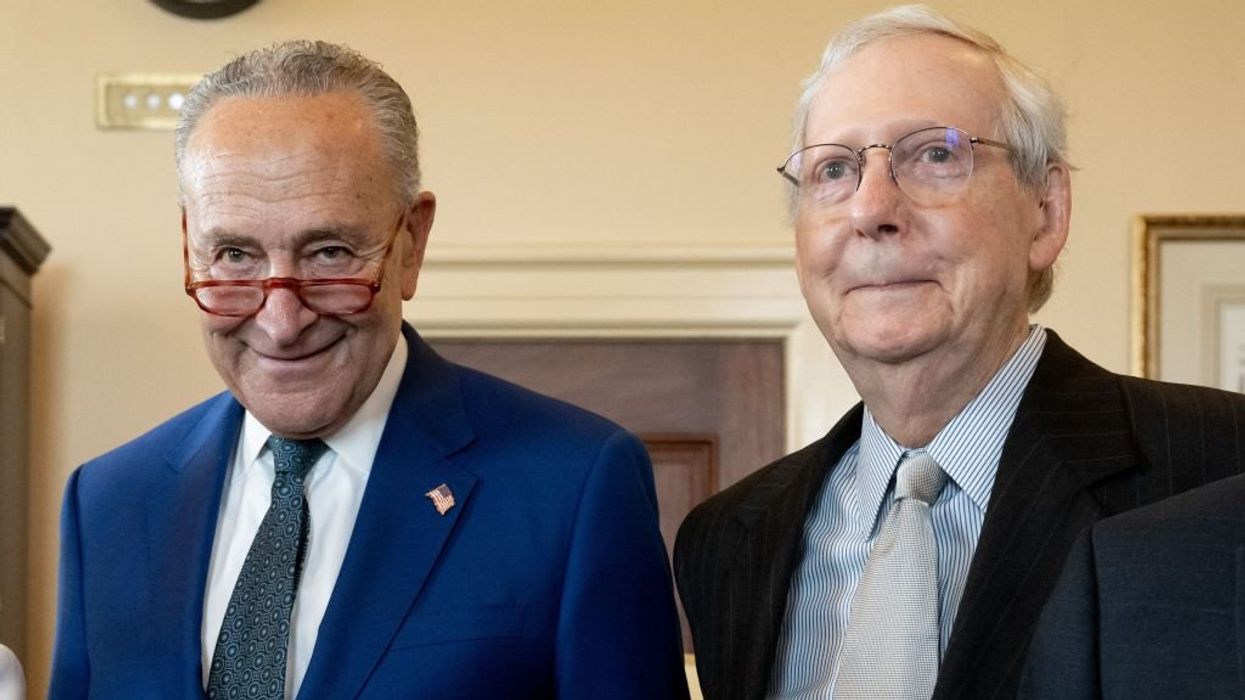

Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

Editor’s note: This article has been adapted from a viral X thread.

Congress once again fights over funding bills to avert a government shutdown, and Americans are once again treated to the corporate media dutifully reciting talking points of both Democrat and Republican appropriators. Fiscal conservatives — and millions of Americans concerned with our skyrocketing national debt and wasteful spending — are predictably sidelined and ignored.

So here is the real story.

The “law firm” of Schumer, McConnell, McCarthy, and Jeffries (aka “the Firm”) has learned that members of Congress (and voters) don’t like “omnibus” spending bills — that is, legislative proposals that fund all of the functions of the federal government in a single consolidated bill.

This presents a challenge for the Firm, which has for years used omnibus spending bills to manipulate the legislative process. Before we address the Firm’s latest challenge and its response, let’s first review a few of the basic dynamics at play.

An omnibus spending bill is typically written by the Firm in secret, with assistance from a few “appropriators” (members of the House and Senate spending or “appropriations” committees), hand-picked by the Firm. Once written, an omnibus will first be seen by the public — and even by nearly every member of Congress — only days or hours before a scheduled shutdown.

The timing and sequence of a typical omnibus, carefully orchestrated by the Firm, all but ensure that it will pass without substantive changes once it becomes public and that very few elected federal lawmakers will have meaningful input into this highly secretive process. At the same time, the fast (almost mindless) flurry of legislative action at the end of this legislative charade gives it the false appearance of democratic legitimacy.

Sometimes that appearance is enhanced by the Firm deciding to let members vote on a small handful of amendments, but the Firm persuades enough members into opposing amendments that make substantial changes to the original, sacred text.

What’s stunning here is that loyalties within the Firm seem to run deeper than those within each party. In light of that phenomenon, some observers have described the force uniting support for the Firm’s omnibus bills as “the Uniparty.” While rank-and-file members of both parties are adversely affected by the Firm’s manipulative tactics, there is far more resentment toward the Firm among Republicans, who see two constants in the Firm’s impact: (1) government spending inexorably grows, and (2) the spending bills advanced by the Firm tend to unite Democrats while sharply dividing Republicans, producing a net gain for Democrats.

While exceptions can occasionally be found, Republican appropriators are notorious for wanting to spend far more than they want to advance Republican policy priorities, deeply endearing them to the Firm.

Thus, although voters in every state elect people to Congress to represent them in all federal legislative endeavors, the Firm can (and often does) render their individual involvement in the spending process far less meaningful than it should be.

This sort of thing makes the Firm far more powerful, with more power flowing to the Firm every time this cycle is completed. It’s great for the Firm and the lobbyists and special interests able to capture its attention (through home-state connections, political donations, or otherwise).

But this situation is terrible for the American people, who are stuck with the horrible consequences of this shameful dance, including rampant inflation and our $33 trillion national debt.

In a sense, the problem is not necessarily the omnibus itself. In theory, Congress could pass a comprehensive spending bill in a way that didn’t exclude most of its members — and most Americans — from the process of drafting, debating, amending, and passing that bill.

Thus, there’s nothing inherently wrong with the omnibus itself; the true evil lies in the process by which the omnibus is secretly drafted, hastily debated, and then passed under extortion by the Firm.

Many Americans have, over time, developed a basic understanding of omnibus spending bills — at least enough to be suspicious of them. Having heard enough complaints from their constituents, many members of Congress have understandably begun expressing reluctance toward passing any omnibus.

The Firm is aware of that growing reluctance, which it recognizes as a serious threat, given how well the omnibus has served to make the Firm more powerful at the expense of the American people. Clearly alarmed by that threat, some members of the Firm have started to say things like “we will not support an omnibus.”

By saying that, they make themselves sound heroic, responsive to voters and rank-and-file members, and committed to serious reform of the spending process.

That illusion disappears when, on closer inspection, it becomes evident that the Firm’s new strategy is to promise to pass two or three smaller omnibus measures (sometimes called “minibus” bills) by essentially the same rigged process long associated with the omnibus. These are bite-sized pieces of the same corrupt package.

Those leery of the Firm’s manipulation tactics understand 1) the absence of a single omnibus bill and the use of two or more “minibus” bills instead of a single omnibus do not mean the process will be fair or materially different from that associated with an omnibus, and 2) it’s likely that Congress will find itself stuck with a single omnibus, in spite of the Firm’s recent insistence to the contrary.

Given that Republicans currently hold the majority in the House of Representatives, rank-and-file Republicans in both chambers generally believe that the Senate should address spending bills only after they have been passed by the Republican-controlled House, as that approach is more likely to protect Republican priorities.

Congress is supposed to pass 12 spending bills each year, each associated with different functions of the federal government. So far this year, the House has passed only one spending bill — the one known by the abbreviation “MilConVA,” which contains funding for military construction and Veterans Affairs.

The Senate last week moved to proceed to the House-passed MilConVA appropriations bill.

Not content to let the Senate deal with only one spending bill at a time, the Firm decided to create a minibus out of the MilConVA bill by adding two additional bills drafted by the Democrat-controlled Senate Appropriations Committee — specifically those containing funding for 1) agriculture, and 2) transportation, housing, and urban development.

Conservative Republicans in the House and Senate found this move alarming, as it would strengthen the Firm at the expense of Republican priorities and contribute to the eventual likelihood of an end-of-year omnibus geared primarily toward advancing Democratic priorities.

But the Firm faced a hurdle: combining the three bills together in the Senate would require the consent of every senator.

While many Senate Republicans harbored these concerns, most identified conditions that, if satisfied, would persuade them to consent. Most of the conditions involved some combination of technical and procedural assurances pertaining to how the combined bill would be considered and an agreement to vote on specific proposed amendments advancing Republican priorities.

One Republican senator in particular, Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, remained concerned that any agreement would benefit the Firm far more than it would advance Republican priorities. On that basis, he objected, halting the process.

The Firm wasn’t happy. Making its displeasure known, the Firm and its cheerleaders tried to blame Senator Johnson for the Senate’s inability to restore what’s known as “regular order,” that is, the process by which each of the 12 appropriations bills is supposed to advance independently, in a way that honors each member’s procedural rights by allowing an “open amendment process.”

Here’s the irony: what the Firm was proposing was not “regular order.” Far from it. It was a slightly different flavor of the Firm’s tried-and-true manipulation formula.

Because Senator Johnson courageously objected shortly after the Senate voted to proceed to the House-passed MilConVA bill, the Senate may now operate under “regular order” consideration of that bill. We are now unencumbered by the Firm’s manipulative plan to subject the Senate to an unending series of omnibus (or omnibus-like) bills that the Firm can ram through both chambers with minimal interference from rank-and-file members.

Senator Johnson deserves credit for standing on principle and should be thanked for his dedication.

If the entire mess I have just described sounds complex, confusing, and even insidiously opposed to the principles of transparency and democracy, don’t worry: that’s the entire point. It is “what we do in the shadows” in Washington, just draining tax dollars instead of blood from hapless victims.

Together, we can fix this process, which has created so many problems for the American people. But to do that, we have to push back against the Firm.

If this message resonates with you, please retweet and otherwise share it with anyone who might listen, and ask your members of Congress to stand up to the Firm.

Mike Lee is a Republican U.S. Senator from Utah.

Mike Lee