© 2025 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

"Round the city, round the clock; Everybody needs you." — Frank Ocean

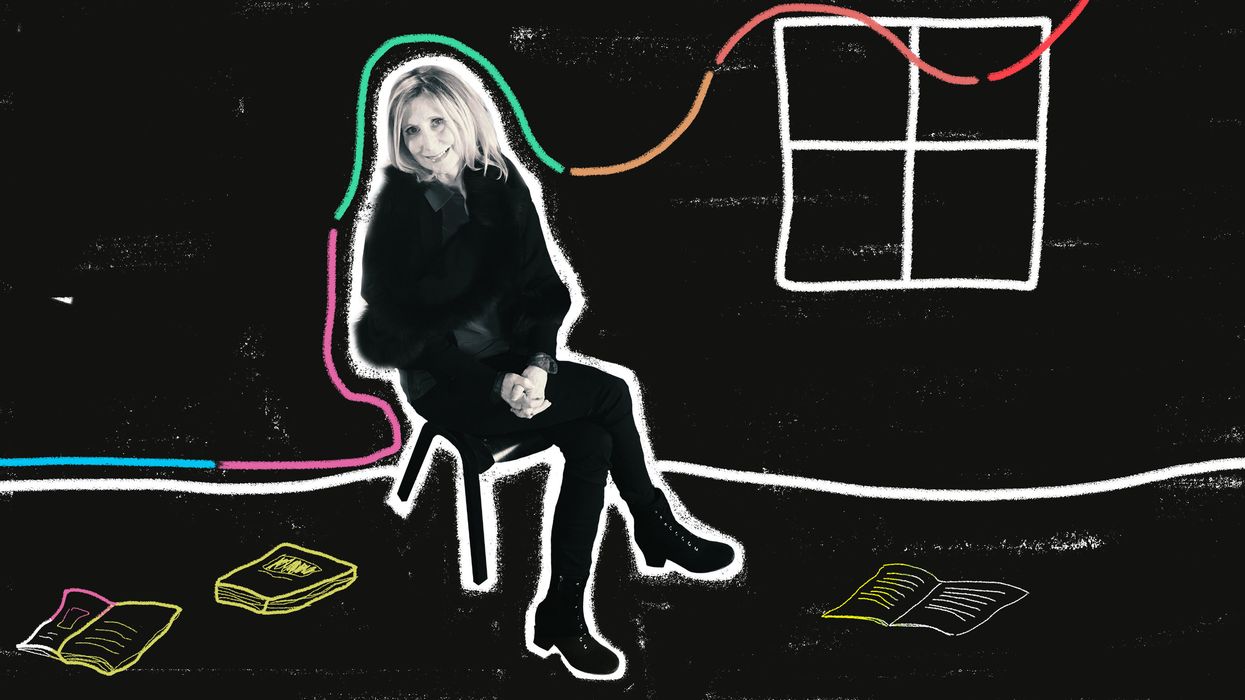

The chaos can wear on her, but American author and philosopher Christina Hoff Sommers handles it like she handles the rest of life: with patience, with a sense of humor, with a mind for cornering truth.

Still, the past few months have weighed on her. The past year. Her mother died. She was Hoff Sommers' best friend. Her father passed, too. He was always making jokes, reminding her to laugh.

Before that, she lost her husband in 2014.

Every day, unexpectedly, she remembers. Sometimes, it's when she's eager to share a funny story. Then, remembering, she pauses in the silence. Other times, she catches herself using the present tense, which no longer applies.

But she always plods forward, always keeps moving. One day, her friend Sally Satel, a psychiatrist and professor at Yale turned excitedly to Hoff Sommers: "I know what you are: you're a manic depressive, but you only have the manic, never the depression."

"Still," said Hoff Sommers, "sometimes it seems like they're still here."

Introducing: Izzie, the Maltese poodle

Then, Izzie bounded onto the porch like a New Orleans funeral band. Izzie being Hoff Summers' Maltese poodle.

Grrrrr. Grrrr. Growl. Yap! Yap! Yap-yap!

"Now, Izzie," I said, "that's a microaggression."

"Oh," Hoff Sommers said, sighing, "she commits MACRO-aggressions!"

The first weekend of May 2019, I visited Hoff Sommers at her house in a wildwood suburb of Washington, D.C. We chatted over the course of three days that wove in and out of rain and sunlight. On Sunday night, the sky broke to a steady downfall of droplets the size of pinkie rings.

She was sick of travel. Enough traveling. Enough airports. No more 14-hour flights to different hemispheres. She was home, and it felt good to be home, and that's how it was going to be for a while: at home, peacefully, beside her vivacious 2-year-old MaltiPoo.

We chatted on the second-story balcony of her tidy home — which a friend aptly described to me as "a literal dollhouse."

Growing up, she never had rain, so she loves it when a storm erupts.

"A lot about teaching is dependent on good acting," she said. "Performing. Being a good storytelling. To get my students interested I would tell stories. Every lecture I approached it as a big challenge to win their attention."

At the center of the pollinated table, a sash-and-ribboned bottle of Charles de Fère Rosé, pink bubbly wine, which we tilted into ornate glasses adorned with flowers, ovalur. Hoff Sommers enjoys a nice rose champagne. Cheers, salud, or whatever the French say. We strode through a bottle easily. Then a second, over tortilla chips.

"My mother was a feminist," Hoff Sommers said, "but, she liked men. For her, feminism was about friendship, and equality, and not hectoring and nagging and screeching."

Which, the latter was the case at a recent talk Hoff Sommers gave at UCLA with protesters.

"They were so bitter. And so furious with me. 'Cause I was questioning these sacred truths, and I'm thinking to myself, 'If I were in law school, and somebody came and said a bunch of stuff I didn't agree with, I would ask them questions — "What's your source?" Why this drama? Why be furious?' They help me, in a way, because they're like Exhibit A of my argument. Because that's not normal behavior for law students. To be, not just skeptical — that's fine — but angry."

"And the fact that they believe this fantasy about their own oppression," she continues. "They're women. They're at UCLA Law School. They must be intelligent: It's not easy to get into that school, but sometimes I think that radical feminism is this kind of conspiracy theory for intelligent people. It's a complicated theory. You have to think your way into it, but you should be able to see through, and they can't."

She often speaks in floaty drifts like this, like a Joy Williams short story.

But, to be clear: she supports protests. She admires gusto. The civil rights movement, the women's movement, the gay rights movement: all genuine civil rights struggles, and they were reality-based. They were necessary.

"The world's changed a lot," she said, in a way that was almost melodic. Then she tilted her head into the shade. Like if Stevie Nicks had chosen philosophy over witchcraft and cocaine.

A Rose in the dark

She was dressed for California. Her blouse. A plush of rose, variations of pink in a hallucinogenic design. A perfect analog to the calibrated hush of unbidden nature around us. Then she said that the truth is out there, waiting, no matter what anyone says. Meaning, it's time to decide.

Correspondence

"I've been lecturing for many years," she said, "and I have a lot of people who write to me, years later, and say, 'I saw you and I was furious, I hated you, but, now I have to tell you, it helped me.'"

Just this week, Hoff Sommers got an email from a woman who said she felt clearer now, relieved. When she thought about it, it was pretty funny.

Performance

Hoff Sommers has written articles for The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, USA Today, the New Republic, the Chicago Tribune, and Times Literary Supplement. She has appeared on "Nightline," "CBS Evening News," "Crossfire," "Eye to Eye," "20/20," "Inside Politics," "Equal Time," "Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher," and "Oprah."

In the unfortunate case that this profile leaves you dissatisfied, you can read any of the others written about Hoff Sommers by the New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and the London Times.

She heard from a friend that Christopher Hitchens loved her article, "A holiday in Hell for junior," about the feminist attempt to re-brand "take your daughter to work day" so that sons would undertake the task. He found it hilarious. "To have written anything that would be praised by Hitchens, that made me very happy."

She considers herself more an academic than a journalist (her primary sources tend to be books, not people). With a bachelor's degree from New York University and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Brandeis University, with an emphasis in ethics and contemporary moral theory.

She taught for a couple years at the University of Massachusetts at Boston. Then as an assistant professor of philosophy at Clark University, where she was promoted to associate professor after six years. In 1994, "Who Stole Feminism?" It was a gob of spit in the face of modern feminism. Or at least the form that it had begun taking, what she calls "gender feminism." And aligns herself with "equity feminism," a classically liberal approach that strives for "economic, educational, and political equality of opportunity" between men and women.

Then, three years later, she left academia, and joined the American Enterprise Institute as W.H. Brady fellow.

She doesn't miss the classroom. It was hard work. Today, she'd get in trouble, she thinks. She sort of did. Ruffled feathers. With support from her husband, she did not recoil, did not forfeit her beliefs in service of academia.

And since those early days, she's been a controversial figure.

With each large iteration of culture, each major shift in the climate of men and women or left and right, Hoff Sommers, embodying Big Lebowski-level nonchalance, finds herself in front of an audience. Different, each go around. Different ages, different beliefs, different reasons for their dejection or hope or their off-kilter glare.

Because somehow, every time, she also manages to piss off a fresh wave of people. Recently, they're yellers, stompers, criers, chanters, shriekers, and — yes — they are seasoned interrupters. The general demeanor of which was currently being channeled through Izzie.

"Oh, no, Izzie: You're a militant feminist," she said. She laughed. "I suspected that."

And Izzie kept barking, inciting every dog in the neighborhood, until Hoff Sommers dropped a stern Hebrew word, and Izzie listened. Everyone listened.

Then she added that it's not really like that, when she gives talks. Not every time.

"One out of 10," she reckoned.

But when it does happen, it goes viral. And somehow the Southern Poverty Law Center, an organization that Hoff Sommers grew up admiring, labels her "an enabler of male supremacy" and accused her of giving "a mainstream and respectable face to some [men's rights activists'] concerns."

"I'm not really an advocate for men and boys so much as an advocate for truth," she says.

Sometimes, it worries her. She often wonders, "Wait a minute, why am I the only one? There aren't many professors, or former professors. Why wouldn't there be more?" she paused, rhetorically. "There are now — because it's starting to go bad, but it still troubles me."

Because what if they're right? What if that's why she's out in the wilderness alone. But — nope, nope — when she examines their ideas, genuinely and sympathetically, she spots all the logical inconsistencies and ideological tactics. And the hostility she faces doesn't make it any better.

Think of it. Because even if it only ever happened one time, it'd be hard to shake. You start your speech to a large, mostly attentive crowd, having spent years reading and studying and fighting for a reputation, only to have five hecklers screech every time you start a sentence, accusing you of hatred, insulting your personally, calling you evil. In those moments, Hoff Sommers stays polite. A little silly. Playful. If the heckling drones on, she talks over it. Wig wags. Play-frowns. Half exclaims. Exposes irony, verbally and with gypsy-like hand motions.

But sometimes the hecklers' road-rage-like invective never subsides, and, the whole time, it's fireworks in a library and everybody's nervous.

'South Park'

Hoff Sommers has often wondered, "Why can't people laugh anymore?" Which is how her sons got her into "South Park."

She loves the way co-creator Matt Stone described his politics: "I hate conservatives ... but I really f***ing hate liberals."

Corner store

Her answers have the lovely down-spiral of a philosopher. She paused, blinking a lot. Changed directions.

Her father — God rest him — was always proud of her writing. He would rush out to buy her work. One time, she was interviewed by Playboy. Her dad was in his 80s. He wanted to get a copy, but he had recently moved to a small town, Brattleboro, Vermont ("California had gotten too conservative for them").

So he crossed the state line to New Hampshire and bought it. Shifting at the counter, he told the clerk, "I'm only buying this because my daughter's in it!"

Izzie, the Conqueror

"Fetch," said Hoff Sommers, "go fetch," then returned to the topic of feminism. "But we wanted to be liberated. Now they want to be protected. From young men. Who are nice guys. I mean 99% of them. Of course, any college can have a sociopath or a deviant, but most of them are nice guys. What must it feel like to be a young man?"

She's interrupted by Izzie, but barely stopped her line of thought, with a side-glance, saying, "Fetch! Fetch!"

"And to have to cope with this notion, and these young women that've been brought up with this theory about 'toxic masculinity,' and they're filled with suspicion, paranoia, a pessimism," she continues, "and that bothered me from the beginning. Because I was inspired by these young women and — what a good little doggie! What a good little thing! Now give it. Give it. Sit. Come. Down. Down. Good girl — then there's the theory about patriarchy. It's a twisted theory, supported by specious statistics. But I think it has a very negative effects on the minds of young women. They take it seriously. And they become humorless. They become angry. They panic.

"And that's what I see: a moral panic, a contagion of hysteria. Because of toxic feminism. This is a real thing — fetch, if you want a treat, fetch," she said throwing a neatened dog toy over the wooden railing. "We're gonna have a lot of fetches in this interview."

Diagram of activism

First, activists get steamed. Left, right, liberal, conservative — doesn't make a difference. They come from the fringe. Next, the snide, unwavering putdowns, usually on Twitter. Which are picked up by journalists and framed as part of a legitimate trend. Resulting in greater tensions. Resulting in actual trends. Then, a petty round of harassment or even doxxing, occasionally spilling over into real life, at times disastrously.

(As a journalist, I fully realize my role in all of this. But, just know, I'm one of the good ones.)

Either way, the bickering intensifies.

Someone gets fired for some stupid comment they made in calmer times. Feelings hurt, egos wrecked. And now it's more people steamed, and more activists vaunting the sewer-like dark of social media.

"Pick a side," say both sides. And, by the way, somehow not picking a side, not choosing the middle path, has become the rotten choice?

The personal and the political have fused, like how red and blue make purple, irreversibly.

After a few squabbles, your politics shape your identity. What you believe dictates who you are and what you're worth. So you fight until you're empty. Run, bawling, for cover. Or maybe you got lucky, in which case you prowl for another target, righteous and glib but ultimately alone.

It is at this phase of the great fight that we seek cultural emissaries, the representatives we have chosen, the deacons of our new society. People like Kanye West, Joe Rogan, ContraPoints, Bernie Sanders, Dave Rubin, Beyoncé, Donald Trump — whoever speaks for you.

Consistently, for the past 20-plus years, in this culture draft-day, Christina Hoff Sommers is elected matriarch of the laissez faire.

Snakepit

She would later describe her 1998 speech at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, Massachusetts, as the moment she was "excommunicated from a religion I didn't even know existed."

As part of the American Philosophical Association, she read a paper that was critical of academic feminism. Boy, that did not sit well. One woman nearly fainted, red then pale, combatively flustered.

Then, they started hissing. Hoff Sommers must have had quite the ornery grin as she waited for a chance to speak.

"I have to request that there be no hissing," she said, fighting a grin, "it marginalizes people with lisps."

Rescue ship

Both of Hoff Sommers' parents lived through tragedy, but they didn't burden her with it. Instead, they got her interested in the world, always giving her books, always taking her to debates and movies, out into culture. Her father fought during World War II, a rescue ship, in the Pacific, 19 years old. Never talked about it until much later. Her Uncle Bob, an artist in Big Sur, fought in the Battle of the Bulge, saw a friend explode.

When she was 6, Hoff Sommers' parents took her to a production of "My Fair Lady" at the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera. The allure of the stage, the capsizing burst of the music, the play of sound and dance — she wanted to stay, to always belong, onstage.

Growing up, the family's religion was the Democratic Party. Politics. Loving Kennedy. Hating Nixon. "I remain a registered Democrat, out of respect for my parents."

She was in seventh grade, barely a teenager, when former President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Nothing in her world had been so impossible. The president that she and her family had loved — he was dead. And in that god-awful way.

She watched the live feed as Lee Harvey Oswald took a .38-caliber belly-shot from Jack Ruby's $62 Colt Cobra. Now she'd lost a hero and watched a man die on TV.

When Hoff Sommers was 16, her mother gave her a copy of Bertrand Russell's "History of Philosophy," it was OK — she shrugged when she told me — but she gravitated toward philosophy. After high school, she spent a year in Europe. Paris. Her sister was living in Holland. Also, she did a kibbutz.

Then, off to New York University. At the time, there were no rules in New York City. And colleges were just moving away from parietal hours. One reason she went to NYU was to explore the theater scene in New York City.

Ultimately, she chose philosophy over theater.

She hopes that, if she were a student today, she wouldn't be persuaded, misled. She worries that she would. She wasn't a clear thinker before college. She had an interest in tarot cards.

But the professors at NYU wanted students to be rigorous thinkers. "You had to be able to justify your beliefs, make your assumptions clear, show that your conclusion followed from those premises. We had to do that. And it was not sentimental. It was not indulgent. They did not care about our feelings." She pauses. "Thank goodness."

Maybe her biggest regret in life is that she never became a singer.

Izzie, the Militant

Hoff Sommers put Izzie inside, so she stared out like she was in jail. Twenty minutes later, she barked and clobbered the glass door.

"See what she does," Hoff Sommers said, mouth agape, "I mean she's a terror," laughing in a playful, lavish way, turned, "You're a witness: Am I oppressed by this dog? It's like living in a police state."

The Outback

"I didn't know what to expect," she said. "I did not expect that. I didn't realize that Australia was that polarized. Just like we are."

The video is out. She's afraid to watch it. She may never. She considers herself a better writer than a speaker. And, on the scale of her speaking engagements, that was, well, not her best … according to her, at least — a lot of people think she did quite well, especially given the circumstances.

It was billed as the THIS IS 42 #FEMINIST Tour.

March 29, 2019 — Sydney Town Hall, Sydney, Australia

March 31, 2019 — MCEC Plenary 2, Melbourne, Australia

The idea was to put Hoff Sommers onstage with Roxanne Gay, author, professor, activist, prolific op-ed writer, feminist. Because Hoff Sommers was all of those things as well, but the women arrived at wildly different conclusions.

When she agreed to the dates, Hoff Sommers imagined that, after the debates, she could get a drink with Gay, "That just for a second we could be two girls having a laugh."

Hoff Sommers taught philosophy for years, so she knows how it feels to have her deeply held beliefs challenged, even upended. And she's always open to that possibility.

In the months leading up to the event that had been billed as "two feminists with different perspectives sit down and have a discussion," it turned into a spectacle on par with a Mike Tyson weigh-in — post-prison.

During an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Gay called Hoff Sommers a "white supremacist." Then refused to retract the accusation, instead calling her "white supremacist adjacent," a designation she maintains to this day.

(Hoff Sommers is Jewish.)

"I absolutely think that there is room within feminism for conservatism. There's nothing wrong with that," she says. "I think what feminism, and what most cultural movements are saying, is we're not going to tolerate bigotry."

Gay added, "It does legitimize her viewpoint, which is really unfortunate. But I think I am up to the challenge of pushing back."

Like many of the protesters Hoff Sommers has encountered, Gay is a no-platformer, so she believes that people with dangerous ideas should be silenced. That the best response to hate is ostracism. Problems arise when various groups cannot agree on definitions for "dangerous" and "hate."

Gay has invoked accusations of white supremacy with success before. The Bannon controversy: "White supremacy does not deserve a platform. Xenophobia does not deserve a platform. And either you are willing to hold that line or you are not," she wrote. (Bannon was subsequently pulled from the program.) And the time she pulled her book from Simon & Schuster in protest of their deal with Milo Yiannopoulos.

Two weeks from the Australia tour, the Christchurch mosque shooting took place in nearby New Zealand — 51 dead. Murdered while worshipping. In their sacred place. Targeted for their religion. The shooter was an actual white supremacist.

While Hoff Sommers was venturing toward Australia alone, Gay and her squad of lawyers and agents and who knows who else were playing a heavy round of PR, talk shows and articles, with all the fury of Twitter at their backs.

In her interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Gay called Hoff Sommers' use of the term Factual Feminist "a move right out of Donald Trump's playbook where you try to reorient people's relationship to truth."

She added, "That sets up a lot of really weird things where the woman of color is, what, working with fairytales? And the white woman is working with facts? I don't think that's a great way to frame the debate."

A New York magazine article chronicled the bizarre turn of events.

So Hoff Sommers was still reeling from the whole fiasco during my visit: "When I said in Australia that I believe that the free market is what helped liberate women — if you look at the rise of feminism, and most of the liberation movements: they developed because capitalism provided a foundation of prosperity so that there could be higher levels of human flourishing — Roxane Gay said, 'Capitalism didn't help black women,' then the crowded just went 'Yay!'. What does that even mean? What was she thinking?"

The audience howled and booed every time Hoff Sommers spoke. They yipped and whistled and screamed "I love you" any time Gay so much as rolled her eyes, which she frequently did.

"There was nothing I could say, nothing that would calm them down," Hoff Sommers told me. "There was no way to come back with answers. And I kept thinking, 'What can I say so that the audience won't tar-and-feather me?'"

She has never gotten used to it — the belligerence, the disruption. She often wonders, how had someone like her, someone with such a sunny perspective, someone with what she calls a "trusting, optimistic view of life," how had she gotten into this raging battle, this war of ideas?

In the early 1990s, a friend warned her. Told her she was challenging people who seemed aggressive and invested and obsessive, and that, if she didn't stop, she would become the focus of their ire.

One enlightening passage from the New York article:

At the first event, [the moderator] asked, 'What is feminism?' and 'What is intersectionality?' These were … terrible questions to ask an audience that had paid up to AU$247 to attend a feminist exchange of ideas … the prices were higher than usual because of Gay's large fee).

Some people who attended the Australia talks have demanded a refund.

"Words cannot kill a frail mind," writes Maya Angelou, "unless it's allowed."

When it's allowed

Hoff Sommers appearance at Oberlin College on April 20, 2015, marked the first time she had a police escort, and how fitting that both officers were women.

Some professor had written a scolding op-ed about Hoff Sommers' "discursive violence," a common accusation leveled at her — basically, that controversial words are literally an act of violence.

"What they fail to notice," said Hoff Sommers, "is that words are how we avoid violence."

The campus whirred with anxiety. As if a dangerous inmate had escaped prison, armed and lustful. Students organized safe rooms. Many protest signs were taped and painted. The general disdain for Hoff Sommers frightened the administration. Left them concerned for Hoff Sommers' safety. Hence, the police escort.

The students actually let her speak. But not without plenty of jeers and hyena noise. At one point, a philosophy professor in the audience turned to the students and asked them to please be more respectful.

"Sit down!" shouted the protesters.

Then, the grown man sat down.

Americans were wound a bit tight at that time, spring of 2015. People were afraid that Civil War II could break out at any moment. Six months earlier, the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, had enflamed deeply held tensions. Riots. Botched referee efforts by a then-tired President Obama. And peeking in from the side of the stage was Donald Trump, who would announce his candidacy for president a month later, to mostly laughs and yuks.

After Hoff Sommers finished her speech, three diversity and wellness facilitators took stage and gave the students instructions on how to deal with any post-traumatic stress they might have endured from sitting through Hoff Sommers' talk.

The policewomen ushered her through the back, to the marked van.

In total, 30 students rushed out of the lecture, in various states of agony. Thirty students, and one therapy dog.

The dream

An unknown number of Hoff Sommers' followers are people devoted to the task of scouring her each tweet in the hope that she'll write something awful.

"I don't hate them," she said. "I think, 'They don't know me, and maybe they don't know themselves,' so I don't feel any contempt."

She tilted her head sideways.

"Now. Will I like them? No, not necessarily. But, I don't have contempt. And, if you're on the left today, and you're active, on a regular basis, you are convinced of the absolute worthlessness of vast numbers of people."

Then she paraphrased Buddhist-minded German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer: "Contempt is such a dangerous emotion because, when you have contempt for someone, you have the conviction of their absolute worthlessness." She let the phrase dangle in the air like a prop skull in an actor's hand in a performance of "Hamlet."

"Now, I do not have that view of anyone," she added. "Anyone. And even if you said, 'What about the worst criminal?' part of me would wonder, 'What in their life led them to this?' I'd be frightened, if it were some ruthless murderer or something, but almost anyone, I'm just open to hearing their story, and seeing it from their point-of-view."

She paused for a moment, then said: "Rather than have the culture war, I'd like to have a dog farm."

Optimism

Then there was Fred, her husband. Philosopher Fred Sommers.

He was older than her.

She will forever admire his life story, the rough-and-tumble upbringing on Manhattan's Lower Eastside, an impoverished immigrant family, into a rough-tangled boyhood, a street life. He was brought up as an Orthodox Jew, but he left religion for philosophy, a student instead of a rabbi. Still, he didn't like it when Hoff Sommers called herself an atheist.

He earned enough that she didn't need to work. "I could have been a dilatant and not worked at all," she said. "But I wanted to. Despite myself, and because of Fred, I stayed in. And he was very manly. And my boys are, too. It's completely wonderful, and sweet, and good."

"Do you believe in God," I asked.

"Nope," she said. Then paused. "I mean, let me put it this way. I admire people who do — that's not the word — I envy people who do. And I agree that faith may be a gift. ... I was not given that gift. And I just can't justify it intellectually. But — I'm not an adamant atheist. Because there's so much that's mysterious to us."

On the drive to Hoff Sommers' house, I listened to an interview on NPR with Daniela Jampel and Matthew Schneid, who'd just published an article in the New York Times about the ever-evolving career roles of men and women. Hoff Sommers mentioned the article, somewhat randomly.

Fred had no expectations of housekeeping ("Why make a bed when you're just going to get back in?"). Hoff Sommers, she keeps things tidy, especially her house, in the aroma of trees and rain.

The Times article worried her, she added, because, in it, men's and women's differences are painted not as a natural harmony, but a toxic divide.

"Fred did things that were indispensable to the happiness of the home," she said. "He was a great father. He didn't even like sports that much but he watched it all the time with the boys. I had my boys, two wonderful boys, who are gentlemen; my dad, the sweetest man ever; and my husband, who, I would've dropped out of grad school if he hadn't encouraged me not to. Those were the men in my life."

She paused, in the quiet.

"I might never have had the confidence to be a fighter," she added, "but Fred would always say, 'They can't say that! Go ahead.'"

He was her cornerman, cheering her on in the fight. "Somehow, Southern California meets this New York street fighter and I became a little like him." She nodded, adding that Fred never became like her, the California hippie chick. She stopped, nodding, nodding. "He was fearless. And I respected that. I respected his stoicism."

"Was he the love of your life?" I asked.

"Oh, yeah," she said, without hesitation. "I miss him every day. And I wish he were here to see all of this. Because he'd have a lot of opinions. And now I'm really on my own."

The air settles into an even deeper quiet. Not even a bird singing or a car revving and Izzie leans forward as if drawn by the vulnerability. "Because I always had him. And no matter what happened, no matter what anybody said — he just loved me."

Later, she'd watch Chris Farley clips on her iPad, and laugh and laugh. A Puccini song drifting out of the corner-shelf Sonos speaker. That precious tidy living room, full of personal treasures and knotted pillows and evening light. A book titled, "Land of Hope," rests on the coffee table. The glinting vases and gold-filament rug, variegated nuances of purple and ivory and, her favorite, rose.

She'd just talked about widowhood, about love, about marriage, about funerals, about so many beautiful and devastating life events. Yet, her presence was still featherlike. She'd start laughing halfway through a light sentence, randomly — not really laughing, more like swirling her tone, amused, always drawn into a certain word or phrase, only to drop her pitch again and move along, because what else can we do?

Land of hope.

Thank you for reading. Check out my Twitter. Email: kryan@blazemedia.com

Want to leave a tip?

We answer to you. Help keep our content free of advertisers and big tech censorship by leaving a tip today.

Want to join the conversation?

Already a subscriber?

Staff Writer

Kevin Ryan is a staff writer for Blaze News.

The_Kevin_Ryan

more stories

Sign up for the Blaze newsletter

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.

Related Content

© 2025 Blaze Media LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the stories that matter most delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, and agree to receive content that may sometimes include advertisements. You may opt out at any time.